After successive years of failing to meet high-stakes testing and accountability mandates required by NCLB (2002), schools across the nation have undergone numerous restructuring practices in an effort to “turnaround” their failure. When schools fail to demonstrate AYP and receive successive years of unacceptable accountability ratings, NCLB stipulates additional sanctions be applied to the school (Berry & Herrington, 2011; Kowel & Hassel, 2005; Price, 2010). Low-performing urban campuses introduce governance approaches and implement reform strategies designed to turn around the pattern of persistently dismal academic performance (Mead, 2007). Under the federal guidelines in NCLB, school districts have several options that can be used to establish alternate governance structure. This includes:

- Reopen the school as a public charter school.

- Reconstitution—replace all or most of the school staff, which may include the principal, who are relevant to the schools’ inability to make adequate yearly progress.

- Enter into a contract with an entity, such as a private management company, with a demonstrated record of effectiveness, to operate the school as a public charter school.

- Turn the operation of the school over to the state education agency if this action is permitted under State law and the State agrees, or implement any other major reconstitution of the school’s governance arrangement that is consistent with the NCLB principles of reconstitution (Hassel, 2006).

After a decade of trials and changes, a growing number of schools face the threat of organizational approaches such as permanent school closure (Duke, 2012). Turnaround policies and sanctions are unique to each state, as some appear to be more likely to take over and/or close schools relative to the other options required by NCLB (Murphy & Meyers, 2007). For example, by the 2005-2006 school year— three years after the passage of NCLB— approximately 1,750 schools across the country were already in the federal restructuring phase of school improvement. Seventy percent of these schools were located in seven states (CA, GA, IL, MI, NJ, NY, PA). The state-to-state disparity can be attributed to the variations in design and enforcement of state accountability systems and to the political will emanating from state capitals to run local schools (Wong & Shen, 2002). Despite hesitancy in some states, the number of schools in the restructuring phase of school improvement more than doubled by the 2007-2008 school year (CEP, 2008) and was reported at over 7,000 in the 2010-2011 school year (CII, 2012).

President George H.W. Obama and Secretary Duncan have extended the call to address chronically low-performing schools, articulating that a “vision for a 21st century education begins with demanding more reform and accountability, coupled with the resources needed to carry out that reform.” In 2010, it was announced that Texas would Receive Nearly $338 Million to Turn Around Its Persistently Lowest Achieving Schools. Has school turnaround worked in Texas (and elsewhere)? Stop for a moment, and count on your fingers (you will only need one hand…) how many school turnarounds have been profiled as consistent success in the news media, blogs and elsewhere…In fact, Chicago Will Close Down Some of Arne’s “Turnaround” Schools as Failures.

In my view, the success or failure of school turnaround calls the bluff of accountability and high-stakes testing because it is the codified endgame of these policies…

To understand the success or failure of school turnaround, our new peer-reviewed study published by Urban Education utilized surveys and interviews with school leaders from four turnaround urban high schools in Texas to understand student outcomes before and after school restructuring and reconstitution. While some organizational changes were apparent; overall, respondents cited rapidly changing technical strategies and haphazard adjustments from external sources as a great challenge. Reconstitution also magnified challenges that existed before and after restructuring efforts. Most importantly, the evidence suggests that school reconstitution did not immediately improve student achievement, impact grade retention and decrease student dropout in the study schools.

Our Conclusions: The newly expanding practice of school restructuring poses a great dilemma for schools that are currently selecting and implementing restructuring intervention practices (Berkeley, 2012) and states that are searching for proven reform strategies to adhere to RTTT grant application requirements (Berry & Herrington, 2011). Petersen (2005) even suggested that states are making up the rules as they play the game. Research on the governance structures of high-performing schools stresses stability in leadership; however, many troubled schools have frequent turnover in leadership and staff that result from teaching and managing in high stress environments (Holme & Rangel, 2011; Smarick, 2010; Milner & Tenore, 2010). School districts are reluctant to relinquish power to the state and there is little evidence that suggests that state takeover of schools and/or districts (i.e. Detroit, Compton and Oakland) will improve student achievement over the long term.

What this study of four urban high schools suggests is that school districts, state education agencies, and the education community are in the early stages of understanding the impact intervention practices that work best for turning around low-performing schools. What is especially problematic is the influx of inexperienced and emergency teachers that respondents reported. The higher rates of novice teachers and year-to-year variance relative to the district and the state in these schools over the long-term is a pressing concern.

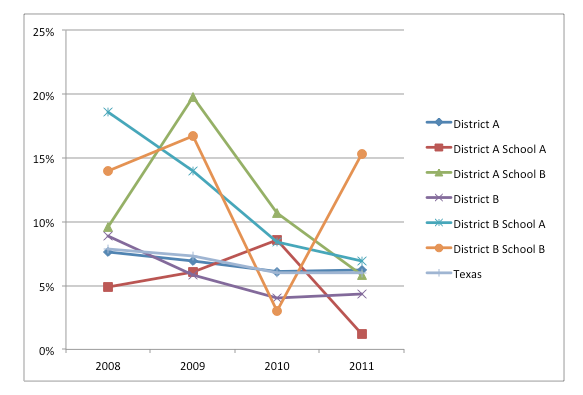

Percent of Beginning Teachers (2008-2011)

Also notable is that only in one of the high schools did the principal remain before and after the school was reconstituted. In fact, the principals in the high schools under study also typically did not survive beyond the year that they were interviewed. In 3 of the 4 high schools, they were assigned new principals by the district each year following reconstitution. As a result, a primary area for future research is the impact of the discontinuity in leadership on the success of school turnaround.

There are several lessons for policy and practice from our sample turnaround schools that states, school districts, and schools can bear in mind as they move forward in implementing reconstitution and restructuring mechanisms, including:

- Stable and valuable governance, leadership, and teacher quality continued to be largely absent in the turnaround process of low-performing high schools in Texas.

- Reconstitution and restructured school changes are drastic and there is no conclusive evidence yet in Texas that chronically low-performing high schools are consistently increasing high-stakes test scores and meeting accountability standards after the turnaround process.

- Many Texas high schools were reconstituted both pre and post NCLB. Yet, formative and summative independent studies have yet to empirically demonstrate improved individual-student outcomes in the study schools [HISD, I am willing to independently study the Apollo schools if you are reading this].

In sum, school turnaround is the high-stakes end game of NCLB and, perhaps, calls the proverbial bluff of systemic reforms. For standards-based, high-stakes testing and accountability to be efficacious, they must be consistently successful in schools that have long been cited as low-performing. After two decades of high-stakes tests and accountability in Texas, the fact that policymakers and the media are not trumpeting the successes of a legion of turnaround schools is telling. Even more problematic is the scarcity of existing evidence detailing its effects on student outcomes.

Citation: Hamilton, M., Vasquez Heilig, J. & Pazey, B. (2013). A nostrum of school reform?: Turning around reconstituted urban Texas high schools. Urban Education.

See all of Cloaking Inequity’s posts about School Turnaround.

[i] In a follow-up conversation, one of the respondents stated that the beginning teacher proportion dropped because budget cuts in the district and region necessitated by the Texas Legislatures $6 billion cut to education statewide made it harder for existing teachers to move to other schools in the area. As a result, in his school, they only hired one new teacher in 2011 to join staff of about 130 teachers (the staff had been about 150, but 20 teachers left the school and were not replaced due to the budget cuts).

See the brand-spanking new full peer-reviewed article here.

For references, please go to the paper.

Please Facebook Like, Tweet, etc below and/or reblog to share this discussion with others.

Want to know about Cloaking Inequity’s freshly pressed conversations about educational policy? Click the “Follow blog by email” button in the upper left hand corner of this page.

Twitter: @ProfessorJVH

The problem with the reform of schools is that the prerequisites have not been met: the reform of our entire society. As long as students come to school poor, hungry, homeless, and fearful, schools reforms will continue to be unsuccessful. Whatever happened to “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses, yearning to be free”?

LikeLike

Congrats to you, Dr. Hamilton, and Dr. Pazey on the publication. Looking forward to it!

LikeLike

With such a quick turnaround rate as these restructuring practices are supposed to create, how does an organization like a high school benefit from a swift switch in leadership? A change in such a high leadership position, say a principal, will create a huge shift in the atmosphere of the school. Teachers, students, and parents alike will all take time to create those trustworthy bonds needed to allow leadership to be effective. The change in dynamic can force some schools to lose their “best practices” that were creating healthier learning environments. If the school is already not progressing at the acceptable rate then restructuring it will only bring on lower ratings. Another vicious cycle of public education? Nope, couldn’t be!

In my experience in an elementary school a shift in even a significantly respected teacher leaving or retiring can change the culture of the school not only for the other teachers, but again for the students and the families associated with them. It takes time to adapt and create a postive, productive learning environment. And, we all know without a supportive environment no one is going to be teaching their best and children will certainly not be learning their best.

LikeLike