The landmark case Brown v. Board of Education set a new legal precedent in the United States that dismantled the “strange career” (Woodward, 2001 [1966]) of Jim Crow. The purpose of this law, from the standpoint of the social engineers of this Civil Rights Movement, was to change to the social, economic, and educational opportunities for African Americans and other racially marginalized groups in this nation (Guinier, 2004). In the context of schools, this new legal precedent sought to open new opportunities for schooling that would have a direct impact on the life chances of historically underserved communities. The philosophical idea of desegregation was to break down the barriers of legalized segregation in schools and integrate non-White students into White schools that had better facilities, a greater amount of school resources, and a wealth of structural opportunities to increase historically underserved communities’ chances to learn and thrive in a democratic society. In other words, Brown pursued a radical egalitarian (Dawson, 2001) approach that sought to have America live up to the highest ideals of democratic theory—which suggested that each individual live to their highest potential.

Legal scholars (Bell, 1980; Dudziak, 1988; Guinier, 2004) and educational scholars (Grant, 1995; Ladson-Billings, 2004; Hess, 2005), however, have outlined the gaps between the intentions and the realities of Brown. Some have even considered whether Brown was a good idea for African Americans—particularly when looking at the case retrospectively (Brown, 2004; Guiner, 2004; Grant, 1995). A growing and significant body of literature about the resegregation of schools (Clotfeller, 2006; Eckes, 2003; Orfield & Eaton, 1997) has come out of these considerations of Brown. This body of work has convincingly shown that what was achieved through Brown in the dismantling of the de jure racial segregation in U.S. schools has all been lost to de facto racist policies and practices that have thwarted the overall impact of the case. The striking data to come from this work plainly illustrates the failures of Brown in helping to desegregate schools.

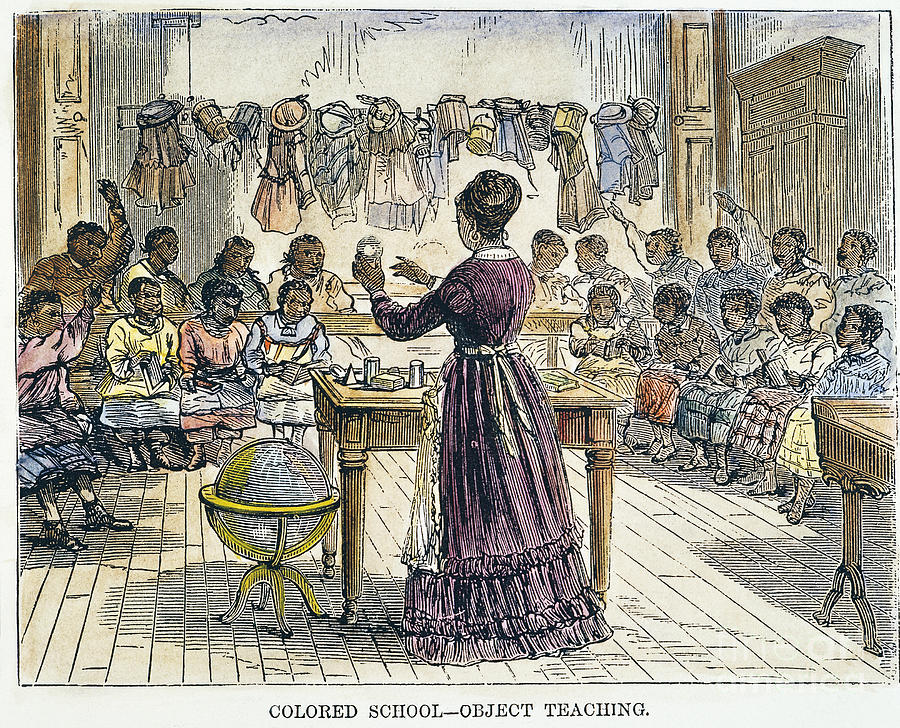

Although much of this work has shown the problematic ways in which school policies helped to create a racially segregated schooling context across the United States (Clotfeller, 2006; Eckes, 2003; Orfield & Eaton, 1997), some of this work has also looked at the context of schools before Brown and asked questions about the quality of schooling for Black children in segregated schooling context (Kelly, 2010; Siddle Walker, 1996). The retelling of the pre- and post-Brown narrative raises a question that W. E. B. DuBois posed in 1935 (b): “Does the Negro need separate schools?” Although the intent of this new chapter is not to explore the historical and contemporary implications of this question, we draw from this question as a historical guidepost for our analysis. We maintain that implicit in this question are additional questions about who should teach the African American child and what the African American child should be taught. In keeping with DuBois’ question, we explore the contours of African American curricular critiques and revisions from the 1930s to the present.

It is not our intent to provide an exhaustive review or in-depth history of this topic, but to highlight some of the common tensions around curriculum in a pre- and post-Brown era and show how curriculum for African Americans followed a similar path of inclusion and exclusion as the historical trajectory of schools in a pre- and post-Brown era (Brown & Brown, 2010b). In this new chapter we highlight a similar narrative to the one told about school resegregation, with specific attention to what we call the resegregation of knowledge. By knowledge we are specifically talking about the school curriculum. In examining the pre-Brown and post-Brown discourse of school curriculum one can find a similar historical trajectory as outlined by the previous scholarship found in pre-Brown and post-Brown educational context for African Americans.

We first outline the early 20th century critiques and challenges to school curriculum from the perspective of African American scholars living within a segregated schooling context—what we call the era of “segregated knowledge.” Then we draw the readers’ attention to the post-Brown era that sought to make sense of curriculum within the efforts of integration—what we call the era of “multicultural and integrated knowledge.” We follow with a discussion about curriculum revisions and the neoliberal and neoconservative assault on Black curriculum inclusions in the 1990s and in the present. We conclude with an extensive discussion about the intersection of a narrowed curriculum with high-stakes testing and NCLB-inspired policies around teacher quality.

What do we conclude relative to this history and present milieu of curriculum mean in relation to the context of resegregated schools for African Americans? What the history of curriculum and African Americans illustrates is a dominant trope of marginalized knowledge (King, 2004). However, as this chapter illustrates, this marginalization was situated within the racialized time and space of which curriculum questions were addressed— the reform context has mattered. Looking at the master narrative of African Americans and curriculum as a whole within a pre- and post-Brown era reveals the continuities and discontinuities with respect to the historical context of the ongoing knowledge debate about African American imagery. The continuities seem obvious, in that the conditions of African Americans have remained marginalized whether they were informed by a racial ideology of inferiority, or drew from social-psychological theories of self-concept or neoliberal policies designed to remove and diminish the placement of African American multicultural histories and experiences. In the end the results were the same—African Americans were problematically rendered and access to quality curriculum restricted across historical reform contexts.

Brown, A.L., Vasquez Heilig, J. & Brown, K. D. (2013). From segregated, to integrated, to narrowed knowledge. In J. K. Donnor and A. D. Dixson (Eds.), The resegregation of schools: Race and education in the twenty-first century. New York: Routledge.

For all of Cloaking Inequity’s posts on segregation click here.

Also, check out the post “Illusion of Inclusion,” Article about Race and Standards in Harvard Educational Review for another piece that I co-authored with Dr. Anothony Brown and Dr. Keff Brown.

Please Facebook Like, Tweet, etc below and/or reblog to share this discussion with others.

Want to know about Cloaking Inequity’s freshly pressed conversations about educational policy? Click the “Follow blog by email” button in the upper left hand corner of this page.

Twitter: @ProfessorJVH

Click here for Vitae.

Please blame Siri for any typos.

Leave a reply to Pile of Old Books vs. Citizens as Critical Participants in the Great Education Debates | Cloaking Inequity Cancel reply