Are some charters’ practices new forms of colonial hegemony? When examining current discipline policies and aligned behavioral norms within charter school spaces, postcolonial theory is useful because of the striking similarities between problematic socialization practices and the educational regimes of the uncivilized masses in colonized nations. A number of postcolonial theorists focus on multiple ways that oppressors dominate their subjects and maintain power over them. For example, while working as the Dean of Students for a charter school in New Orleans, it took me some time to realize that I had been enforcing rules and policies that stymied creativity, culture and student voice. Though some of my main duties involved ensuring the safety and security of all students and adults at the school, investigating student behavioral incidents and establishing a calm and positive school culture, I felt as if I was doing the opposite.

My daily routine consisted of running around chasing young Black ladies to see if their nails were polished, or if they added a different color streak to their hair, or following young men to make sure that their hair wasn’t styled naturally as students were not able to wear their hair in uncombed afro styles. None of which had anything to do with teaching and learning, but administration was keen on making sure that before Black students entered the classroom that they looked “appropriate” for learning. As if students whose hair was natural or those whose parents could not afford a uniform tie could not achieve like others who possessed these items.

Most times, teachers and administrators scolded Black students for their appearance before they even spoke in morning. If a student did not have the right shoes, they would be placed in a holding area until their parent could be reached. Sometimes, if their parent could not be reached, those students remained in that area the entire day and given detention. I have absolutely no problem with enforcing school rules or policies, but when schools penalize and prevent Black students from learning and engaging in the classroom because their parents do not have the resources or simply cannot afford the uniforms, I take issue with that and I voiced my displeasure many times.

Each day, I could have up to 10 students in my office, affectionately dubbed the T.O.C., (time out center) by the end of the first period. Students continued to come throughout the day as teachers would simply not allow students to come back to their classroom. Most of the teachers guilty of this behavior were (TFA) Teach for America cohort members who were great hearted individuals, but could not control their classrooms. Most had no sense of cultural competence and frankly felt as if they did not need to know the kids to teach them. When a few teachers attempted to develop relationships with Black students and parents, it seemed disingenuous and painful. Many times, they avoided parent phone calls and conferences because they felt like a confrontation would occur. Students would enter my office daily and say “she put me out for nothing,” “I just got up to sharpen my pencil and she said go to Mr. Griffin, that lady don’t like me.” Teachers regularly abused the mark system we implemented at the school as well.

Students could be sent to my office after receiving 3 marks, but some teachers would focus on certain kids and as soon as they made a sound, they would give them a mark. If I had twenty students sent to me by lunch time, I would have to take those students to lunch duty with me, take them back upstairs afterwards and help teachers manage their classrooms at the same time. Each day, I would average 25-35 students in detention without any follow-up from teachers. Detention became a dumping ground, especially for students exhibiting disabilities (ADHD, ED, etc).

Most Black students with or exhibiting disabilities were pegged as outliers at the beginning of each school year; they were unfairly targeted by some teachers who had deficit attitudes sometimes before even meeting the students. Many times, these students were placed on a “special plan” where their parents had to pick them up early and work would be sent home with them to make it seem like they were learning something. However, the work was never turned in or even requested from teachers. If they were not sent home early, they were given detention. If their behavior was perceived as disruptive in detention, they were given some form of suspension. 98% of the students were Black, but if you happened to be a male and exhibited some form of disability, chances are that you were treated harsher, suspended numerous times and spent several hours a day outside of the learning environment. Many were even sent home for the year after taking the LEAP (Louisiana Educational Assessment Program) standardized tests and treated like throwaways.

When we tried to implement response to intervention (RTI) with students who either possessed or exhibited disabilities, they were immediately moved from tier 1 to tier 3 and some were subsequently placed in special education even though this did not fit the needs of the student. The idea to segregate certain students considered (outliers) was due to administrative convenience and because most teachers perceived them as being unruly, troubled or just plain too academically deficient to be in class with the other students. This allowed teachers to not be held accountable for teaching all kids and prevented Black students from receiving valuable instruction time.

Lastly, everything at the school was done in a militaristic/prison fashion. Students had to walk in lines everywhere they went, including to class and the cafeteria. The behavioral norms and expectations called for all students to stand in unison with their hands to their sides, facing forward, silent until given further instruction. The seemingly tightly coupled structure proved to be inefficient as students and teachers constantly bucked the system in search of breathing room. The systems and procedures seemingly did not care about the Black children and families they served. They were suffocating and meant to socialize students to think and act a certain way. In the beginning, we were teaching “structure,” but it evolved to resemble post-colonialism. Vasquez Heilig, Khalifa, and Tillman (2013) stated that “education was and still is used as a hegemonic form to monitor, sanction, and control civilized people.” Thus, postcolonial theory (Fanon, 1952, 1961; Memmi, 1965; Said, 1978) offers a critical framework through which urban educational policies and practices can be understood and critiqued (DeLeon, 2012; Shahjahan, 2011). They continue their analysis by stating that “at base, post-colonial theorists interrogate the relationship between the legitimized, conquering power and the vanquished subaltern, and ask questions about who defines subjectivities, such as knowledge, resistance, space, voice, or even thought.” Fanon (1961 ) argued, “Colonialism wants everything to come from it.” Essentially, colonizers delegitimize the knowledge, experience, and cultures of the colonized, and establish policy and practice that will always confirm the colonial status quo. In other words, it is important to note that postcolonial studies, though often thought of as relegated to a particular period, are actually also a reference to thoughts, practices, policies, and laws that impact marginalized Black bodies enrolled in charters during the current educational policy era.

Vasquez Heilig, J., Khalifa, M., & Tillman, L. (2013). Why have NCLB and high-stakes reforms failed?: Reframing the discourse with a post-colonial lens. In K. Lomotey and R. Milner (Eds.), Handbook of Urban Education. New York: Routledge. (See the post: A Quandary for School Leaders: Equity, High-stakes Testing and Accountability)

Please Facebook Like, Tweet, etc below and/or reblog to share this discussion with others.

Want to know about Cloaking Inequity’s freshly pressed conversations about educational policy? Click the “Follow blog by email” button in the upper left hand corner of this page.

Please blame Siri for any typos.

Julian, great post. I’m just reading this today, as it was reposted today on the SeattleEducation blog. I wrote a similar piece about colonia thinking and its impact on schools and students. You can find the essay on my blog here: http://wp.me/p4fwaD-18

The post is based on a talk I gave at NCTE this past year.

LikeLike

I have more thoughts on this issue than I can fit into a comment, but I’ll try to be brief. Note that this is coming from a TFA, who grew up in New Orleans, taught in a charter school in NO, taught at a traditional public school in St. Bernard Parish, and went to the 1 or 2 white public schools from K-12:

1) Classroom discipline is the most difficult skill to learn for a new teacher. I believe that some of these militaristic policies are a shortcut for new teachers—especially those that don’t understand the community. While teaching at the KIPP charter school, I realized that it was helpful, yet impersonal in my first year. More veteran teachers did not have to be as rigid.

2) What he describes as prison-like/militaristic (i.e. lines, structure, etc.) is appropriate for elementary school, but dehumanizing beyond that. Jean Gordon Elementary had lines, fingers on lips, heads on desks, etc. Lusher Extension (middle) and Franklin High didn’t—because it wasn’t age appropriate.

3) Uniforms/dress code/appearance. I never wore a uniform from K-12. I learned just fine and dress more appropriately and professionally than the majority of my professional counterparts. Before teaching at a majority white working class conventional public school (not charter), I saw dress codes as radicalized. White public schools didn’t have them, the black ones did. And talk to any older Franklin graduate from the early and mid ‘90s. Many of them attest to the positive correlation between increase in black student percentage and increase in dress code strictness. In fact, as McMain (and I think Karr as well) went from a mixed school to a black one, uniforms were instituted.

Fast forward to my teaching of working class white kids in St. Bernard Parish. They wore uniforms, most hairstyles were banned (even long hair for boys), boys couldn’t even grow out their natural facial hair (do you know how cool the 3-4 8th graders with facial hair are in other schools?)! Even their freaking socks had to be white! This has NO relationship with education —so charter schools that serve black kids are not the only culprits. Maybe it’s a socioeconomic class thing.

Dress codes have some value—in the 90s kids were being murdered for Jordans & Starter jackets (but it’s not the 90s anymore); it saves the poorest of kids from being teased; hoop earrings for girls are dangerous if the school has a lot of fights; short skirts & shorts for girls can distract other students (but isn’t a deal breaker); sagging pants and guys w/ earrings can be argued as not appropriate for a professional setting. I agree with Melissa that learning to follow rigid rules helps you in adulthood. What I don’t understand is why the rules are noticeably less rigid in middle class white school. Perhaps in the real world, poor kids generally have to work rigid hourly jobs with time cards and strict management, while middle class people have less rigid salaried careers.

4) Special Ed. I taught Special Ed at a working class school that was 70% white. My SpEd classes were 50% black male. That is a HUGE problem. HUGE!

LikeLike

OMG….I’ve been deconstructing this notion for years. From my experience at a Godforsaken charter school as an Intervention Specialist (Special Needs teacher) being told by the “superintendent/owner” (who was granted the school by the state of Ohio but later retracted when complaints were filed due to him being a convicted felon…a police officer selling drugs out of his cruiser) that my salary was contingent upon how many students I labeled special needs to my recent Graduate Assistantship position in an urban charter school in Ohio. My cohort member and I were discussing how these schools are the new plantations and perpetuate forms of neo-segregation. GREAT read!

LikeLike

This is trite, but true- if it walks and quacks like a duck; it’s a duck- or, “neo-segregation” so keep on deconstructing and posting.

LikeLike

What you describe sounds like the ideas behind Fascism.

LikeLike

My experience as a teacher- 40 plus years now- began in New Orleans, and I remained there working either directly for the Orleans Public schools or with them for thirty years- as a teacher, Upward Bound coordinator, advocate for student leadership programs in all N.O. high schools, as an ESR coordinator for a school-wide conflict resolution program, as a researcher in the completion of my doctorate, a Ph.D. in educational leadership at UNO. The descriptions by Griff19 above rings true. In my opinion, based on 30 years of observation, the colonizers will always lean toward the status quo – charters or no charters, vouchers or no vouchers, or, a public school system in contrast of a private and parochial school system as still exists in N.O. New Orleans, in many ways operates like a third world – banana republic- many who live there, believe. It’s no accident, I think, that the Greek Revival home that the President of Tulane University enjoys on St. Charles Ave., was donated by the a powerful family from the United Fruit Company- the ultimate Banana Republic Corporation.

In New Orleans, the colonial “process” is very complex and reaches high social and political places. Former N.O. mayor and Urban League President, Marc Morial recently came out for (endorsed) CCSS, yet, he like many from his “class” in N.O. never attended public school. His elitist view, born of privileges, quite different than the students described in this article sees education as Sec. Duncan sees it, I believe. Creoles in N.O. have experienced discrimination in N.O. to be sure- especially since Jim Crow. Mr. Plessy (a Creole) who could pass as white was really trying to establish the old order of privilege for Creoles, “Free People of Color” (better educated than most whites) when he and his cohorts took their famous case to the Supreme Court out of New Orleans in the late 1800s. They lost and it wasn’t until 1954 with Brown v. Board of Education that legal de-segregation rights were returned to them and former slaves alike.

A former colleague of mine, and a person with deep roots in the N.O. Creole, “Free People of Color” community distinguished herself, as a Principal, by turning an inner city N.O. school completely around and winning national recognition. She went on to Harvard in their esteemed Urban Superintendent’s Program and earned a Harvard doctorate and high positions in urban education districts; New Orleans, Memphis, Newark, N.J., and Atlanta. Her leadership forte was Curriculum Development, and she won her districts high marks for innovation and continuous improvement with NCLB testing.

Bill Gates and other e-industrialists and politicians associated with the so called “educational reforms” and “testing moments” in education supported her and I believe, in typical colonial fashion. Then came a manufactured “testing scandal” that served the interests of other “racist” and conservative politicians, -the two most current governors of GA- as I see it, found a popular political agenda to advance their own agenda. In the end, my former colleague was thrown under the bus by Gates and his ilk just as Plessy was thrown to the back of the bus. This “colonialism” isn’t just with students as shown above, but, for those like Julian who attend institutions like Harvard and Stanford too! Colonialism, mentality, reaches the highest institutions like Harvard and Stanford. and into the Corporate Board Rooms too. They will act as if the children being colonized as depicted above, the poor and black and brown and male, are of concern to them. Only half believe it, and be wary!

LikeLike

Powerful stuff. On the one hand I agree that in order to teach and provide an adequate learning environment there must be some form of discipline. There also must be a considerable measure of order and rules that guide the school’s day-to-day operations. However, when rules become unrelated or “tit for tat” then it creates a micro-managed society that entices the rules to be broken. I believe that students can and will adhere to discipline when it is reasonable and has a clear goal, that is evident.

In response, to the entire notion of recolonization, I 100% agree. The environment which you describes seems to be one that doesn’t allow free thinkers or opportunity for expression. That is where the problems arise for me. Enslaving the minds of our future isn’t healthy; it creates a situation where they can no longer see the forest, for the trees.

Great post..

LikeLike

This article is a perfect example of why I would like to see people sue school districts for violating the Americans with Disabilities Act. http://unprison.com/2014/01/29/are-schools-violating-the-american-with-disabilities-act-every-time-a-kid-goes-to-court/

LikeLike

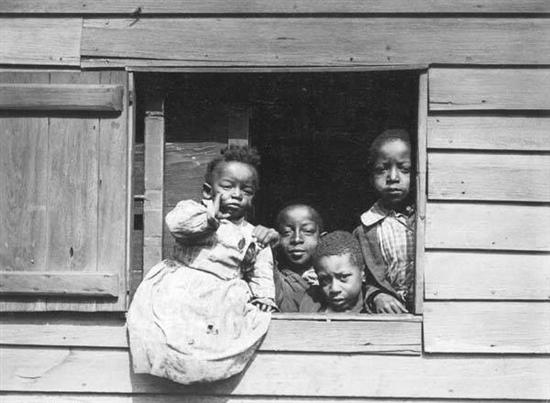

Does the photo reflect the kind of situation that you found in the school, though? I find that implied link offensive. The adolescents at the school have SCHOOL, with adults who are there to help. Do we know that about the children in the photo who came before them?

LikeLike

I am sorry, but I don’t understand your question. Could you restate it?

LikeLike

I take pamela carroll’s comment to mean that the photo posted is not of today’s students in the school but comes from an earlier era when white eyes saw black people as picturesque, as ‘natives,’ as ‘uncivilized.’

I take the point to be: “This is how we STILL view Black kids, even in a modern charter school. It isn’t working. Don’t do it.”

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Crazy Crawfish's Blog and commented:

More insight and examples of the TFA and chart school mentality that will be coming to a public school near you, if we don’t put a stop to it.

Can you share which charter school(s) you worked for in NOLA?

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Quaderni del carcere immaginaria.

LikeLike

A profoundly sobering account of the reality not the rhetoric of the charter school experiment in New Orleans. Thank you.

LikeLike

Hello. I had to stop reading at the ADHD paragraph part. The way the New Orleans charters schools are treating these kids is disgusting to me. I’m a product of the public school system so I guess I can’t relate to what these kids are going through.

Privatized charter schools are going to ruin this country if they’re being ran like this. And Black students will have nothing to show for it. Shame of a Nation!

LikeLike