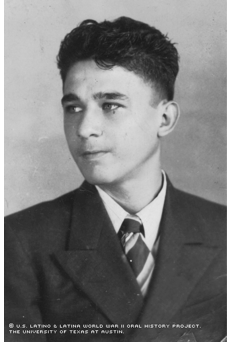

Thank you to all of the veterans who have courageously served our country. This post is dedicated to my tía Minnie Cadena who recently passed and was a participant in the University of Texas Voce Oral History Project and my tío John G. Reyes who was KIA 1944.

This post is also dedicated to the all of the Heilig, Scott, Vasquez and Cadena who have served our country bravely.

In a new chapter we honor the memory of Latino veterans and their families. This chapter was recently published in the new book Latina/os and World War II: Mobility, Agency, and Ideology.

The citation for our chapter is:

Rodríguez, A. A., Vasquez Heilig, J. & Prochnow, A. (2014). Higher Education, the G.I. Bill, and the Post-War Lives of WWII Latino Veterans and Their Families. In M. Rivas-Rodriguez & B. Olguin (Eds.), Latina/os & World War II: Mobility, agency and ideology, Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Higher Education, the G.I. Bill, and the Post-War Lives of WWII Latino Veterans and Their Families

In 1897, a federal district court in Rodriguez v. Texas declared that the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and subsequent federal policies, conferred upon Mexican Americans a “White” racial status for naturalization and classification purposes. Thus, despite the “separate but equal” decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, Latina/os should have had equal access to the same public schools as Whites. However, racial bias was pervasive. Mexican American “greasers” faced cultural prejudices analogous to the racial animus suffered by African Americans, with several high profile lynchings, and city governments like Houston actively encouraging repatriation during the Great Depression.[i] Professor E. E. Davis of the University of Texas, asserted in a 1923 publication that White American children did not want to attend school with, “the dirty ‘greaser’ type of Mexican child,” and should be required to do so. Instead, Davis advocated that Mexican children be placed in separate schools until they were able to contribute positively to society.[ii] It is within this context that we will explore the experiences of Latino WWII veterans in U.S. schools pre- and post- war.

This chapter begins by briefly reviewing established scholarship on the structural racism that Latina/os faced in the U.S. educational system. It then describes the elementary and secondary educational experiences of several Latino veterans from The University of Texas WWII oral history project database. We conclude with profiles of three WWII Latino veterans derived from follow-up interviews[1] that focused specifically on their higher education experiences pre- and post- war. Little has been written about the lived experiences of Latino veterans who returned from service to enter the hallowed gates of the academy. We ultimately show the survival heuristics and pathways to success of several Latino veterans despite living in the midst of racism within the broader society.

Latino Education in the World War II Era

The highly racialized educational contexts that denigrated the culture, heritage, and language of Mexican Americans was evident through the system of schooling in Texas, California and other states where large concentrations of Latinos were living. World War II ushered in a new era of American society, one with increased economic prosperity and with new educational possibilities to some Latinos who previously would not have had the opportunity to participate in secondary schooling and beyond.[iii] In 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed into law the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, known colloquially as the G.I. Bill (P.L. 78-346, 58 Stat. 284m). This Act provided a path for WWII veterans to access higher education, an institution that was once the playground of the rich.[iv] Created as a measure to inoculate the U.S. from another financial disaster, as when World War I veterans returned to the home front with a “$60 allowance and a train ticket,”[v] the G.I. Bill, unexpectedly, helped create a highly educated citizenry, and a powerful economic and technologically advanced society.[vi]

Of those impacted by the passage of the G.I. Bill were African American, Latino, and low-income servicemen in general, students who otherwise would have had little chance of accessing higher education. Provisions of the G.I. Bill had the United States government provide financial assistance for tuition, fees, books, and supplies, as well as a stipend, for WWII veterans to pursue their education,[vii] reduced the “opportunity costs” of attending higher education.[viii] Research has demonstrated the African American veteran participation in higher education due to the G.I. Bill helped create a Black middle class[ix] and increased civil participation, including Civil Rights Era activism.[x]

Early Education Experiences of WW II Veterans

Many Latinas and Latinos of the World War II generation attended segregated schools where they faced prejudice and limited educational opportunities. Several veterans recounted the difficult environments in which their elementary school classes took place and how they struggled to attain an education. Many obstacles kept Latino/a students from completing their education. Ramón Rivas, an army veteran from Charlotte, Texas (about 50 miles south of San Antonio), described the setbacks Latina/o students faced in simply advancing grade levels. He explained that in Charlotte, Latina/o students remained in separate Mexican schools until the fourth grade, when both Mexican and Anglo students attended the same school. However, he said that Mexican students never made it to the integrated school because Mexican students, “would start 1st grade, stay there two or three years, and then go to 2nd grade, then stay there like that…” The decision to repeat a grade was given solely to the teacher— parent involvement was limited. This story is similar to another VOCES project respondent Nicanor Aguilar of Big Spring, Texas who had a similar story to tell– he told UT-Austin researchers it was only because of a White teacher that his younger sister, Maria, went on to the 8th grade. This retention of Latinas/os greatly impacted the ability of these students to complete elementary school. Even when students were able to advance, family circumstances or the necessity to work often obstructed the pathway to graduation. Raymon Elizondo, an army veteran from Salt Lake City, Utah, shared the difficulties faced by himself and his family in completing school. Although he greatly desired to graduate and break the cycle of low-levels of education in his family, he was only able to finish the ninth grade before he left school due to financial difficulties that led him to begin working with Union Pacific Railroad at age 17. In his family of 12 children, only one sister completed high school.

Other veterans offered specific memories about the discrimination and racism faced by Latina/os in schools. Julian L. Gonzalez an army veteran raised in Chapin, Texas (About 60 miles east of Dallas) recalled being called into the principal’s office after writing “Viva Mexico” on the playground. The principal told him, “You like Mexico so much, why don’t you go on the next train.”Adam Gastelum, a veteran from Tucson, Arizona described the harsh treatment given by a school coach to students caught speaking Spanish. He stated that the coach would pick up students by their sideburns and squeeze the legs of students to the point of bruising as punishment. Paul Gil, an army veteran from Gonzales County, Texas (about 60 miles east of San Antonio), recounted that the teachers hated him for being a “smart Mexican” after he advanced from kindergarten to second grade on his first day of school because of his advanced reading and writing ability that he had obtained at home. Lorenza Lujano, a family member of a veteran from Newton, Kansas, related that she made the decision in the tenth grade to withdraw from school because the “racially prejudiced” environment she and her family faced in school was “too much to bear.” Lujano felt that this environment even led to the false accusation that her sister Esperanza had stolen a cheerleading skirt from the school. Despite these barriers, some Latina/o students, like Virgilio Roel, A.D. Azios, and Julian L. Gonzalez, were able to succeed.

Strategic Interventions: The G.I. Bill, Latino Veterans, and Class Mobility

Of the estimated hundreds, and perhaps thousands, of Latino veterans who benefitted from the G.I. Bill, three from Texas serve to illuminate the impact this legislation had on transforming the racist landscape of higher education for Mexican Americans: Virgilio Roel, AD Azios, and Julian L. Gonzalez. They gained access to higher education and thus access to the powerful positions and increased social capital in American society. All three of these individuals came from impoverished homes and most were successful students prior to the beginning of the War. The funds and entre provided by the G.I. Bill gave them not only an education, but also the opportunity to pursue their dreams to become engineers, lawyer, judges, and community activists. One interviewee described the G.I. Bill as the “education revolution,” one that made it not only possible for him, but other Latinos around the country to pursue their own educational careers.

In these profiles, success by the three veterans is defined by their social and class mobility, positions of authority within the public sphere, increased agency to advocate for social minorities, and the creation of an educational pathway for their children and grandchildren. Though these stories describe obstacles, perseverance and success, it is important to note that the stories are complex and nuanced than this apparent triad. The veterans negotiate their identities, as Latinos, men, working class, etc. as they participated in the Second World War, higher education, and the professional class. Their response was varied from purposely integrating their past identities into their new ones or returning to their former identities with little desire to change. Two of these veterans became judges, impacting their communities.

Virgilio Roel: Leadership, the Law, and the UT Laredo Club as a Catalyst for Educational Desegregation

For Virgilio Roel, the G.I. Bill was not only an entry ticket to higher education, but also the opportunity to stand up to oppressive actions. This profile will chronicle how the G.I. Bill facilitated the work of a Mexican American to question the authority of the state in regards to Mexican American children in public education, as well as battle for equal representation of women and racial minorities in government positions. This is no hero story though. It is a story of man provided with the means to educate himself; a story of a man whose agency and self-efficacy along with the emerging Civil Rights movement that led to extraordinary life. Still, these successes occurred in positions of power, ones where he was able to shape the lives of those who are not in positions of power. For Roel, the affect of the G.I. Bill can be seen far beyond his career and the lives of his children and grandchildren. Individuals from the rural towns of Three Rivers and Victoria, Texas to indigenous peoples of American Samoa have felt its impact of the G.I. Bill on Roel.

As a young boy growing up in Laredo, Texas, on the border of the United States and Mexico, Virgilio Roel was undaunted in his dream to enter higher education after high school. His friends’ shared interest in attending college would propel him to study at the University of Texas at Austin after the war. Also, he had a deep desire to “help his fellow man and woman, and the best path was education.”[xi] During his high school years, he prepared himself education for admission into college via his studying and high school course, but the U.S. entry into World War II abruptly changed his plans. Instead of going straight to college after graduation, in 1942 he was one of 16 million men and women who entered into the military and spent the next three years in the Army first with the 84th Infantry Division then with the 2nd Battalion, 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment. During his time in the military, Roel trained as a paratrooper and even studied at the Ohio State University during his via the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP), studying languages and geopolitics.

Although both of his parents were teachers, he credits his participation in the military as the reason that he entered college. “If it hadn’t been for my military service, I probably would never have gone to college, I would have stayed in Laredo working for $37 a week” as a railroad surveyor.[xii] Specifically, the G.I. Bill had great sway over his ability to even access higher education. “The G.I Bill of rights, which I think is the biggest piece of legislation that I think Congress ever passed, was the one that really started …the ‘education revolution.’ It made [higher education] possible.”[xiii] The funding for his tuition and educational expenses, as well as a stipend, provided him leverage to attend UT Austin. Still, Roel had to work to supplement his time in college. He spent 35 hours a week at the Texas Bookstore and at the Triple XXX Restaurant, a drive-in restaurant, that kept him well fed during his time in college.

During his time at UT Austin, Roel publicly pursued his passion: organizing and confronting oppressive actions he faced. For example, initially he and other Latinos were not allowed to live on campus in the University’s residence halls. He lived off campus with five other students, three from Laredo and two from Mexico, in one room. He and other Latinos successfully pushed the University administration into allowing them access into the residence halls. Roel utilized a column called the “Firing Line” in the campus newspaper, The Daily Texan, to accuse the University, UT President Painter, and high level administrators of discrimination. Through a series of letters to the “Firing Line,” “…we raised some Cain [and] we finally got [rooms in campus residence halls] the next semester.”[xiv]

Additionally, he created the UT Laredo Club, to organize fellow Laredoans at UT Austin. In addition to being a social club, the group spread activism to small towns like Three Rivers[xv], midway between San Antonio and Corpus Christi, and Victoria, midway between Houston and Corpus Christi, educating them on their rights, specifically the educational rights of children. “We use to go on the weekends to organize people in the small towns in [Texas]…to fight discrimination…so they knew their rights as citizens,”[xvi] Roel said. The UT Laredo Club also challenged discriminatory actions, including the Texas Attorney General Price Daniel’s opinion regarding segregation of children based on language.[xvii] This opinion was drafted after the 1946 decision in Mendez v. Westminster case that found that Mexican students cannot be segregated in different classrooms and different buildings due to language.[xviii]Marion Price Daniel Sr., Texas Attorney General, countered that Mexican children could be segregated if they had language deficiencies.[xix] Attorney General Daniel, after rebuffing the invitations from the UT Laredo Club several times, finally attended a UT Laredo Club meeting to hear the group’s case. Influential educator George I. Sánchez also attended the meeting, and Sánchez, Roel, and other members of the UT Laredo Club challenged his opinion. According to Roel, the Attorney General left the meeting with a change of .

Roel excelled at UT Austin, studying History and Government and graduating Magnum Cum Laude in February 1948, finishing his college career in two and a half years with the help of transfer credits from the Ohio State University. After a short summer stint as a railroad surveyor, he hitchhiked his way to Washington D.C. to attend Georgetown University School of Law, getting caught in rainstorms, sleeping on the sides of mountains, and taking buses and trains when he could. When he arrived he slept on the streets because he “didn’t have any other place to go.”[xx] Roel attended Georgetown Law at night, spending his days as a public liaison with the U.S. Department of State and the United Nations. Later, Roel did something no other Latino had done or has done since. He became an Associate Justice for the High Court of American Samoa.

American Samoa, a former colony turned territory, has a large indigenous population, and one that lacked real authority in years right after WWII. Additionally, the High Court of American Samoa is appointed by the U.S. Department of the Interior, rather than by the local government. American Samoans had little power affecting their own judiciary.[xxi] Roel’s position provided him tremendous weight and influence in the lives of American Samoans, and he took his position seriously. During his term as Associate Judge, he advocated for an increase in Native American Samoan judges, prosecutors and public defenders.

After his tenure in Samoa, he returned to the U.S. mainland where he worked for the U.S. Postal Service. There he worked as General Attorney and member of the Board of Appeals and Review at the United States Postal Service. “One of my trips to [the U.S.] I went and talked to the head of the Democratic National Committee, and he offered me [a legal position at the U.S. Postal Service.”[xxii] This was to demonstrate that the Johnson administration was aiding in the cause of Mexican American rights.

Roel did use his time at the U.S. Postal Service to improve the position of Mexican Americans and other minorities. He recruited women and Latinos to positions of authority and sought to change the culture of the agency. “[One of my conditions to accepting the position was] I would go around the country to recruit Mexican Americans and minorities for supervisory positions because they were outwardly discriminated” Roel stated. “Not only that, women were completely discriminated and it was my conditions for accepting the position.”[xxiii]

After the U.S. Postal Service, he was appointed to be the National Director for Conciliation for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, to end discriminatory housing practices. Roel noted that even the “regional directors of the Agency, they themselves did not want to implement the Equal Housing rules and the Equal Rights regulations.”[xxiv] He had to focus on dismantling a culture where there had been “bias for so long.”[xxv] After many years in Washington D.C. and abroad, Roel and his wife yearned to return to Texas.

For Roel, his education at UT Austin and then at Georgetown Law not only afforded him an exciting and varied career in which he was able to help provide opportunities for other minorities, but it also propelled his children and grandchildren to pursue higher education as well. His four children attended college, two physicians and two certified public accountants. His grandchildren also attended college, ranging from community college to graduate degrees. “I was in the first wave of veterans that benefited from [the G.I. Bill], but once our generation of veterans…had university degrees, it was taken for granted that our children [and our grandchildren] were going to go the university.”[xxvi] For Roel, the G.I. Bill, his golden ticket into higher education, not only paid for his education, but lead to education and financial rewards for his children and grandchildren.

Virgilio Roel’s life from a precocious boy in a small border town to his time in Washington D.C. and back is a testament to the impact of his college education, an education he recognizes would have been difficult to obtain without the G.I. Bill. He excelled not only academically, but was politically active, a trait also seen in African American veterans who participated in higher education after WWII.[xxvii] The impact of his education not only touched his children and grandchildren, but also impacted families from rural Texas towns, Native American Samoans, women, and other people of color.

For Roel, his personal, economic and financial success rested on education and the “educational revolution” created by the passage of the G.I. Bill. He believes that the passage of the G.I. Bill created a “golden era” for Mexican Americans, as they had the opportunity to pursue higher education. He continued to stress that his greatest success was graduating from UT Austin. His education provided him resources and choices, to pursue his dreams and aid others. Education for Roel is an act of citizenship. Quoting Dr. Hector P. Garcia, founder of the G.I. Forum: “Education is our freedom, and freedom is everybody’s .”

AD Azios: Translingual Citizenship, Military Service, and Social Mobility

The benefits of bilingualism and multilingualism have been extensively detailed,[xxviii] but in the case of A.D. Azios, it was a matter of life and death. His childhood bilingualism and adult trilingualism facilitated his and his men a safe return from war. It also informed his decision to act as a mentor to younger Latinos and propelled him to pursue higher education and a career in the law. Azios’s story is the story of a man who chose to empower himself through education, before, during, and after WWII.

Arnulfo “A.D.” Azios was born in Laredo, Texas, one of six sons to Mexican parents. His parents had been refugees from the Mexican Revolution and moved their family to several different cities on the U.S.-Mexico border. For Azios, his childhood was filled with other Latino children and families like his, speaking mostly Spanish. Although he knew little English when he began school, he soon became proficient in the language, mastering the language by the second grade.

A gifted student, Azios graduated from high school in 1939 excited about entering higher education. Many of his Mexican American friends from Laredo were heading off to college, and this peer influence acted as a strong inducement to attend higher education. Azios was motivated to be a role model to other Latino children in his community. He delayed his entrance into college for two years, working as a customs broker for an import/export company, until he hitchhiked to Austin to start school at UT Austin in 1941.

That December, over the radio, he heard of the bombing of Pearl Harbor while he was studying with a former roommate. Upon hearing about this act of war on the United States he made a prediction to his roommate, “we’ll whip ‘em in 90 days.”[xxix] Azios continued his studies until 1943, when his Enlisted Reserve Corps was called to active duty. He hitchhiked his way to San Antonio, with 60 cents in his pocket, and enlisted in the Army Enlisted Reserve Corp. He returned back to UT Austin where he was called up to active duty, the UT Austin tower playing “You’re in the Army Now” on the tower bells.

Azios’s ability to learn languages quickly became an asset for him in the military. He scored high on the Army’s entrance exam, and he and other high scorers were sent to different universities around the country to cultivate their skills. Already proficient in English and Spanish, he was sent to the University of Nebraska from September 1943 to December 1943 to study German. This new skill would prove life saving. After his three month German training, he returned to his unit at Camp Maxey in Paris, Texas for basic training, and then shipped out with the 9th Armored Division of the Army to the European theatre of WWII.

During his time in Europe, Azios he would participate in the Battle of the Bulge, and his German proficiency would save both his life and the lives of other American soldiers. During the Battle, Azios was wounded, his eyesight damaged temporarily by shrapnel. He escaped to a neighboring building to hide, but upon hearing German soldiers closing into his location he called out to them in German and was captured.

Azios utilized his German to barter with German guards and civilians, helping his men trade cigarettes for bread and potatoes. Over his four months as a POW time he gained the guards’ trust, which emboldened him to escape. The POWs were being moved to a new location, away from approaching Allied forces. Azios hatched a plan with a corporal to pretend that he and his ten men were resting. During the escaped a German officer confronted the group. On the pretext of him and his men being injured, Azios convinced the German officer that his group was heading to the nearby hospital but had become separated from the rest of the prisoners.

Once they were out of sight of any German soldier they made their way to a dairy farm where they hid in haystacks. The dairy farmers were also prisoners and provided the men with soup and allowed them to hide out on the land. That night they slept outside and were bombarded by heavy artillery. The next day, an American Lieutenant arrived, and Azios, as the leader of his group came out of hiding to salute his superior officer, and the group of ten escapees was saved.

After being rescued, Azios returned to the U.S. where he recuperated and prepared to return to war, this time in the Pacific Theatre. But the war ended before he could be redeployed. Instead of returning to war, he returned instead to school. Azios took the long train ride from Boston to San Antonio, was discharged, and returned to Austin to complete his studies in pre-law at UT Austin.

After the War, the campus was filled with World War II veterans. Azios recounted that, “If you weren’t a veteran people would look down and said, ‘Well, where were you? Where were you during the Long War?’”[xxx] Although Azios did not discuss the social pressure to participate in the military during the War, it is obvious that young men were expected to have fought, and instead of accolades for veterans it was men who did not fight that were singled out.

He also noticed an increase of Latinos on the campus that he believed was due to increased knowledge about college and its benefits. “When I was in high school very few people went to college, very few, so when we G.I.s came back and went in waves the rest of the kids said ‘Hey, I guess I’ll go to school too.’…We set an example for other kids.”[xxxi]For Azios, his military experience provided more than access to financial resources for college. The Army had instilled a sense of discipline in him for both college and civilian life. He was taught to be more dedicated to one’s work and not to put off tasks until later. Azios insisted that the military changed his attitude of typical stereotype about Latinos from: “I’ll do it mañana: [to] “no no, you’ll do it now.’”[xxxii] As individual who taught himself English by the second grade, it is difficult to imagine that he was a procrastinator prior to his Army experience. I

Unlike other servicemen who attended college because of the financial opportunities provided by the G.I. Bill, Azios had already spent two years in college without the benefit, and would have gone to college with or without the G.I. Bill. “It helped me because it paid for my books, my tuition, and $75 a month to live,” he said.[xxxiii] The G.I. Bill helped him specifically by providing him financial resources to attend college, but he still worked grueling hours to afford to go. During his time at UT Austin, he worked as a janitor, a night watchman at the campus gymnasium, and an elevator operator in the UT Austin tower. Azios would work a full eight-hour day and then spend the night studying. It was a lifestyle that he considered, “rough, rough, rough.”[xxxiv]

After he graduated from UT Austin, he attended the South Texas College of Law in Houston, Texas. His law career took off after law school, becoming first an attorney and then a state judge. His time after school was difficult for him and his family. As a young lawyer, Azios made just enough to provide for his family. But he ascended from a firm attorney to his own practice. Then became a justice of the peace, and eventually ended his career as a District Judge in the 232nd Judicial District Court in Harris County. Azios retired at the end of 1993 and began acting as a visiting judge.

Azios’s time as a judge is compelling. He affected the lives of his local citizens, sitting on criminal court bench. Latinos make up a small percentage of judges at all levels of government, often due to a lack of an influential Latino voice and lack of unity of Latino special interests.[xxxv] Azios was able to galvanize support and be elected to the bench. Importantly, when Latinos are represented on the bench, their approval of the judiciary increases as well as their political awareness, as was the case with the appointment of Justice Sonia Sotomayor.[xxxvi] Azios, by his presence on the bench, likely impacted his community’s perception of the local judiciary and the lives of the minority defendants who are overrepresented due to the confluence of a number of social ills (e.g., poverty, lack of education, narcotic policies, etc.)[xxxvii].

The experience of attending college had a profound affect on Azios. He fulfilled a goal of completing college, one sparked when he was still a child in Laredo. He focused on being a role model to younger Latino children and encouraged them to attend college. Additionally, his three children and grandchildren have continued his higher education legacy by pursing their own college careers. Decades after he completed his undergraduate education, college still has a strong appeal to Azios: “If I was a young guy I would go [back again].”[xxxviii]

Julian L. Gonzalez: Non-Traditional Students, Labor and Political Consciousness

When Julian Gonzalez was approached to participate in the writing of this article, he wondered if he would add any value because he did not have “the traditional college experience.”[xxxix] Yet, his is a common story of part-time students, and one of many of World War II veterans.[xl] In 1959, the first year in which statistics on the subject are available, part-time students made up approximately a third of all college students.[xli] Unlike Azios’s and Roel’s story, Gonzalez was not an officer, nor did he have the educational mentors like the two previously profiled veterans. He, like the majority of Latinos then and now, sought to improve their lives through work. He remained working class, moving through the ranks not via his education, but by his hard work and seniority.

Julian Gonzalez grew up in San Antonio, Texas, the child of Mexican immigrants. His father worked for a cement factory, while his mother picked cotton around the Austin-area. School did not come easy to Gonzalez, specifically because he did not speak English well; he failed several grade levels. Yet he continued his education, moving through high school, until his senior year. In 1944, he was drafted into the army. He appealed his draft order to finish high school and was allowed to enter the service immediately after graduating. Unlike Roel and Azios, where the military facilitated their education through skill training at various universities, the military actually sought to disrupt his education. Gonzalez in turn defended his own education, setting up his ability to take advantage of the G.I. Bill. Shortly after graduating high school a semester early he was then sent to Fort Sam Houston outside of San Antonio, Texas.

At Fort Sam Houston, Gonzalez was trained as a combat medic and then sent to Camp Beale in California to ready for his deployment to the Pacific Theatre. In late 1944, he sailed to New Guinea helping to build schools and hospitals. Gonzalez also worked with civilians in the Philippine Civil Affairs Unit, as a member of the Philippines Civil Affairs Unit #10 to construct a government unit. During this time he waited to see action, as talks of an atomic bomb began to circulate. He was never to see battle, as the war ended after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

After being discharged from the military in April of 1946, he returned to San Antonio. Gonzalez had not graduated with his class, as he had already begun his time in the service. When he returned, he had no job and had no money. In essence, his only alternative was higher education. He also wanted to take advantage of the G.I. Bill. Without the “privilege” of the G.I. Bill, Gonzalez questioned if he would have been able to attend college, because of lack of funds. He did believe, though, that he was more mature and focused on the “urgency…to get that piece of white paper.”[xlii]

Gonzalez began his higher education career at San Antonio College (SAC), a community college that is now a branch of the Alamo Community College system.[xliii]After two years at SAC, he transferred to St. Mary’s University in San Antonio, Texas. While he was still in high school, he had dreamed of being a social worker to “help the poor people.”[xliv] This dream is in sharp contrast to Roel and Azio’s work at facilitating change through institutions. Gonzalez desired to meet with individuals on singular basis. These differing strategies demonstrate the complexity of tracks to fight social injustice, and how social hierarchies influence people’s movements. To fulfill this goal, Gonzalez chose to pursue a degree in sociology, with a minor in history, in the hopes of being able to help people in his community. Though he was motivated to become educated and realize his civic ambition, life responsibilities interfered.

Gonzalez worked fulltime as he completed his degree. He first worked as an assistant timekeeper for the San Antonio Portland Cement Company. As he advanced slowly in his coursework, he also advanced at his job, taking on positions of higher levels of authority and responsibility. Consequently, he was limited to taking about two night classes each semester. Gonzalez generally stayed at school late into the night, which left little time for making connections with other students. “I went to night school…you leave there at 9:30 or 10:00 and you’re anxious to get home, so there’s no time for socializing…I didn’t have the [traditional] college education.”[xlv] As is the case with many part-time students, social issues such as housing, transportation, lack of childcare, etc. can interfere and negatively impact the path to college completion. These socially created barriers continue to reinforce social stratification and can cement a perpetual underclass. Gonzalez was able to escape this, at least partially. Unfortunately, he had already had a history of disrupted education; his high school career accelerated to meet an enlistment demand.

This slow pace also deferred Julian’s graduation. By the time he received his diploma, he had spent 13 years pursuing his degree. Five years into his degree he had spent all the money provided by the G.I. Bill and paid the rest out of pocket. Fortunately, his wife, who had attended SAC to receive her nursing degree, “pushed, enticed, and dragged”[xlvi] him to finish his degree. Though he never pursued a career in social work, his degree earned him a position as a manager at his plant, counseling employees on retirement, personal issues, income tax returns, and Social Security benefits.

Another area where his military service and higher education experience benefited Gonzalez was his civic and political engagement. Roach has described the increased civic engagement of African American World War II veterans who utilized the G.I. Bill, particularly during the era of the Civil Rights Movement, versus the lower civic engagement of those who did not utilize the educational resources provided by the legislation.[xlvii] Although Gonzalez was not part of Civil Rights organizations, he had increased civic participation, particularly working in Democratic precincts.

His degree also affected his family members. His wife and one daughter finished their degrees to become nurses, but his other children and some grandchildren were unable to finish their degrees. Gonzalez cited a lack of financial resources as the reason that his other two children and grandchildren were unable to finish college degrees. Though Gonzalez never directly used his degree professionally, the pursuit of education still impacted his personal, civic, and professional development. It is important to note, that his wife, possibly even more than the G.I. Bill, had a stronger and more direct impact on his pursuit and completion of his higher education.

Gonzalez’s story explores the intersection G.I. Bill in creating a pathway and incentive to attend college, yet the social pressures and obstacles that can disrupt and curtail a veteran’s educational career. His story of a part-time student, full-time employee is the common story for Latina/os in higher education. The path to higher education for these students is often community college rather than a four-year research university. These institutions often lack resources, transfer and completion rates are often low, and time to graduate is often extended. It takes other factors beyond a financial aid policy, such as advocates, support structures, and agency to graduate. Even with the G.I. Bill, it took Gonzalez 15 years to graduate, with the constant prodding of his wife. Even with other “success” stories, it is important to note the shortcomings of the policy and the systematic and institutional structures that impede educational careers and stratify those who do not “succeed.”

Education, Agency, and Mobility

For these three veterans, their experience in the military had a direct impact on their higher education experience. First and foremost, the ability to use the G.I. Bill to access, fund, and complete a higher education degree was paramount for these three veterans. Though two had stated that attending college was a given regardless of the governmental stipendsbill, they both also recognized the increased opportunity they had received to gain their higher educational experience. For González, even though his education spanned more than a decade, he said that without the funding and the inducement to attend college via the G.I. Bill, he may not have pursued a college degree.

Additionally, their pursuit of higher education created a legacy of education for their families. Their children and grandchildren went on to pursue higher education at different levels. Unsurprisingly, the two veterans who had participated in post-graduate education also had children that pursued post-graduate education, demonstrating how educational pathways can become normalized and solidified. Grandchildren also benefited indirectly, as they also participated in higher education, from community colleges to graduate programs.

Finally, they became more civic-minded. Whether it was pursuing a career in public service, participating in local political party organizations, or being more aware of the trials of underrepresented groups in their communities and across the U.S, the three veterans profiled demonstrated how higher education, as well as their veteran status, propelled them to be more interested and engaged in higher education. Similar to Roach’s (1997) assessment, participation in WWII along with higher education helped to create a civically engaged, educated class of middle class professionals who would militate within existing political structures for economic and social mobility. In this case, although outliers, these three Latino veterans were able to incorporate and enfranchise themselves into the broader American society. It is clear that these three veterans were outliers. Our respondents used three tactics—the law, interpretation of the law, and grassroots or at least class alliances and organizing efforts (e.g., Democratic party) to expand the benefits to others. These stories and veteran profiles illuminate their success and survival in an otherwise unfriendly higher education and societal environment. Although WWII was costly for the United States, including Latinos, new educational opportunities for some Latina/os did emerge from the conflict.

Thank you.

Please Facebook Like, Tweet, etc below and/or reblog to share this discussion with others.

Want to know about Cloaking Inequity’s freshly pressed conversations about educational policy? Click the “Follow blog by email” button in the upper left hand corner of this page.

Twitter: @ProfessorJVH

Click here for Vitae.

Please blame Siri for any typos.

The authors acknowledge Laurel Dietz and Michael Voloninno for their help with the research that underlies the introduction to the chapter.

Endnotes

* The authors acknowledge Laurel Dietz and Michael Voloninno for their help with the research for the introduction to this article.

[i] De León, Arnoldo. They Called Them Greasers: Anglo Attitudes toward Mexicans in Texas, 1821-1900. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1983.

[ii] Gonzalez, Gilbert G. Chicano Education in the Era of Segregation. Philadelphia: Balch Institute Press, 1990.

[iii] Gándara, Patricia and Gary Orfield. “Introduction: Creating a 21st-centry Vision of Access and Equity in Higher Education.” In Expanding Opportunity in Higher Education: Leveraging Promise, edited by Patricia Gándara, Gary Orfield and Catherine L. Horn, 1-16. Albany: State University of New York Press.

[iv] Ibid.;United States Department of Veterans Affairs. “G.I. Bill History.” Last modified November 6, 2009. http://www.gibill.va.gov/GI_Bill_Info/history.htm

[v] Ibid

[vi] Henry, David D. Challenges past, challenges present: An analysis of American higher education since 1930. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1975; Gándara, Patricia and Gary Orfield. “Introduction: Creating a 21st-centry Vision of Access and Equity in Higher Education.” In Expanding Opportunity in Higher Education: Leveraging Promise, edited by Patricia Gándara, Gary Orfield and Catherine L. Horn, 1-16. Albany: State University of New York Press; Bound, John and Sarah Turner. “Going to War and Going to College: Did World War II and the G.I. Bill Increase Educational Attainment for Returning Veterans?” Journal of Labor Economics 20 (2002): 784-815. Accessed August 9, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3653525

[vii] Roach, Ronald. “From Combat to Campus.” Black Issues in Higher Education 14 (1997): 26

[viii] Bound, John and Sarah Turner. “Going to War and Going to College: Did World War II and the G.I. Bill Increase Educational Attainment for Returning Veterans?” Journal of Labor Economics 20 (2002): 784-815. Accessed August 9, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3653525

[ix] Wilson, Reginald. “G.I. Bills Expands Access for African Americans.” Educational Record 75 (1994): 32-39; Roach, Ronald. “From Combat to Campus.” Black Issues in Higher Education 14 (1997): 26

[x] Mettler, Suzanne. “ ‘The Only Good Thing Was the G.I. Bill’: Effects of the Education and Training Provisions on African-American Veterans’ Political Participation.” Studies in American Political Development 19 (2005): 31-52. Accessed August 9, 2010. doi: 10.1017/S0898588X05000027

[xi] Virgilio Roel, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 15, 2011.

[xii] Virgilio Roel, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 15, 2011.

[xiii] Virgilio Roel, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 15, 2011.

[xiv] Virgilio Roel, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 15, 2011.

[xv] Three Rivers, Texas is known for the “Felix Longoria Affair,” where a Latino WWII veteran was denied chapel services. Felix Longoria, Jr., a Three Rivers resident and Mexican American, was killed in battle in the Philippines in June 1, 1945. Due to the severe damage to his body, his remains were not identified until 1948. The funeral home in Three Rivers refused to allow his body to lie in state because he was Mexican and “the whites would not like it.” The Affair gained national fame through the publication of an article in The New York Times detailing the account. Tejanos rallied against the injustice under the newly created American GI Forum, an organization that gained prominence due to this incident. Then Senator Lyndon B. Johnson secured a place for Pvt. Longoria’s remains to be interred at the Arlington National Cemetery. For more information see Felix Longoria’s Wake: Bereavement, Racism, and the Rise of Mexican American Activism. By Patrick J. Carroll. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003).

[xvi] Virgilio Roel, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 15, 2011.

[xvii] (Tex. Att’y Gen. Op. No. V-128 (1947))

[xviii] Valverde, Leonard A. “Equal Educational Opportunities since Brown: Four Major Developments.” Education and Urban Society 36 (2004): 368-378; 64 F.Supp. 544 (C.D. Cal. 1946), aff’d, 161 F.2d 774 (9th Cir. 1947) (en banc)).

[xix] (Tex. Att’y Gen. Op. No. V-128 (1947))

[xx] Virgilio Roel, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 15, 2011.

[xxi] For a deeper discussion on American Samoa and colonialism see Dan Taulapapa McMullin’s. “The Passive Resistance of Samoans to U.S. and Other Colonialisms.” In Sovereignty Matters: Locations of Contestation and Possibility in Indigenous Struggles for Self-Determination, edited by Joanne Barker, 109-21, Nebraska University Press, 2005.

[xxii] Virgilio Roel, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 15, 2011.

[xxiii] Virgilio Roel, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 15, 2011.

[xxiv] Virgilio Roel, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 15, 2011.

[xxv] Virgilio Roel, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 15, 2011.

[xxvi] Virgilio Roel, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 15, 2011.

[xxvii] Mettler, Suzanne. “ ‘The Only Good Thing Was the G.I. Bill’: Effects of the Education and Training Provisions on African-American Veterans’ Political Participation.” Studies in American Political Development 19 (2005): 31-52. Accessed August 9, 2010. doi: 10.1017/S0898588X05000027

[xxviii] See Angela Valenzuela’s Subtractive Schooling: US – Mexican Youth and the Politics of Caring (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1999) for a detailed discussion about bilingualism and multilingualism.

[xxix] A.D. Azios, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 14, 2011.

[xxx] A.D. Azios, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 14, 2011.

[xxxi] A.D. Azios, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 14, 2011.

[xxxii] A.D. Azios, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 14, 2011.

[xxxiii] A.D. Azios, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 14, 2011.

[xxxiv] A.D. Azios, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 14, 2011.

[xxxv] Merico-Stephens, Ana Maria. “Latinos in Law Professions.” In Encyclopedia Latina:History, Culture, and Society in the United States edited by Ilan Stavans, 425-427. Danbury, Connecticut: Grolier.

[xxxvi] “Who’s on the Bench? The Impact of Latino Descriptive Representation on Supreme Court Approval,” Diana Evans, Ana Franco, Robert D. Wrinkle, and James Wenzel. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Seattle, WA, Sept. 1-4, 2011; Robert D. Wrinkle, James P. Wenzel, Diana Evans, Jerry Polinard, Ana Franco, and Ellen Baik. “Explaining Latino Approval of State and Local Courts: Acculturation, Trust, and Descriptive Representation” (working paper).

[xxxvii] Janet Moore. “Minority Overrepresentation in Criminal Justice Systems: Causes, Consequences, and Cures.” Freedom Center Journal (in press).

[xxxviii] A.D. Azios, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 14, 2011.

[xxxix] Julian Gonzalez, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 14, 2011.

[xl] National Survey of Student Engagement. Student engagement: Pathways to collegiate success. (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research, 2004).

National Survey of Student Engagement. Engaged learning: Fostering success for all students. (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research, 2006). Part-time students’ experiences can become invisible as they are on campus much less than their full-time peers, their responsibilities off-campus, e.g., childcare, working, etc.) can consume their spare and that they are more likely to be older than full-time students (Nelson Laird and Cruce 2009). They also take longer to graduate and are less likely to be successful (Snyder, Tan, and Hoffman 2006). This marginalization may create a sense that their experience in higher education is less valuable, and Gonzalez mentioned this when he was asked to share his story.

[xli] National Center for Education Statistics. Total Fall Enrollment in Degree-Granting Institutions, By Attendance Status, Sex of Student, and Control of Institution: Selected Years, 1947 Through 2009. Accessed April 20, 2011, retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d10/tables/dt10_197.asp?referrer=list

[xlii] Julian Gonzalez, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 14, 2011.

[xliii] Alamo Colleges. 2011. http://www.alamo.edu/

[xliv] Julian Gonzalez, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 14, 2011.

[xlv] Julian Gonzalez, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 14, 2011.

[xlvi] Julian Gonzalez, interview by Angélica A. Rodríguez, March 14, 2011.

[xlvii] Roach, Ronald. “From Combat to Campus.” Black Issues in Higher Education 14 (1997): 26.

I googled hispanic veterans out of curiosity and the picture of John captured my eye, he looks a lot like my older brother, I was more shaken when John has our last name “Reyes”.

LikeLike

Where do you live?

LikeLike

I live in Merced California and have family in Texas, don’t know how long that stretches over though.

LikeLike

To all who have been unjustly SILENCED !!!!

I think this post is incredibly important to recognize and honor the Latino/Latina service members whose history has been “missed” “hidden” or “denied.” I’ve made it my life’s work in resent years to “uncloak” history where our/my dominant culture has “silenced” the voice of various groups! Always, it seems, the “Cloaking” is around issues of power and trying to create a political narrative that fits comfortably within some political agenda! This has happened in education especially, in recent years, as is demonstrated continuously on this EduBlog: “Cloaking Inequity” and again, thanks, Julian for “Carrying On!”

While I don’t have anything to share specifically about Latino/Latina WWII Vets, I can tell you of other personal knowledge. First, I’d like to recognize my dear friend Marcia Kamia and her Dad, a WWII Vet who fought in Europe against the German’s while his Japanese American lived in a Japanese Interment Camp! Her family was taken there from the San Joaquin Valley of CA where her Dad had owned and worked a small farm. Marica’s Dad would come to my classes and show the students WWII mementos and give a talk. Marcia’s was but one more effort outside “high stakes tests” for so called “at-risk” students to really learn.

One person close to my heart for “Uncloaking Inequity” and who I also follow is Mercedes Schneider. Her recent book: A Chronicle of Echoes: Who’s Who in the Implosion of American Public Education. Mercedes posted a piece about her Daddy a WWII Vet. In response I wrote in her EduBlog: deutsch29, the following about another “missed” “hidden” and “denied” WWII, Vet who until recently, this past year was unknown.

Dear Mercedes: Thank you!

I’d like to honor my father, Jack M. Thornburg, and share some “connections” as my Dad just passed this last year. He flew B-24s in WWII from FIJI through the Philippines under Gen. McArthur in the earliest period 1943 after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. He loved the desert in AZ and took me to visit sites where General Patton trained his tank divisions in the Mojave. Mercedes, it’s possible that your dad was there! Your dad may have also survived the Battle of the Bulge with my friend Robert Brown of the 761st.

This is also to my Godfather Sgt. John Anderson, Salinas, CA who survived the Death March in Bataan and who would reassure me when my dad had to return to war to fly B-29s in Korea when I was 8.

“Connections”, Mercedes, – your dad fought with the 761st. Wow! You wrote: During the last several weeks of the war, the 761st Tank Battalion, an African-American unit that earned a high reputation for its effectiveness in combat, was attached to the 71st Division and fought with it.

The reason my dad took me to visit Gen. Patton’s training area in the Mojave Desert where he got his troops ready to invade N. Africa to fight Rommel’s German tank divisions. The trainers were the 761st “Black Panthers” with a slogan, “Come out fighting.” They were initially allowed to train other white units, but, not fight in the war. Then, after D Day Gen. Patton insisted they be sent to him for combat.

It has become of my personal work to assure of the appropriate recognition of a “hidden” WWII, Vet from the 761st, who is still alive and living in Greene County, Alabama. He is also a survivor of the “education wars” that you and I fight, Mercedes.

His name is Dr. (Professor) Robert Brown and he was also the FIRST Black Superintendent of Schools post 65 Civil Rights Act. It was because of Hurricane Katrina that I came back in contact with Robert and have now worked since those days after the Hurricane to assure his recognition. I came back in contact with Robert Brown while traveling toward New Orleans to rescue my son, and Dad’s Grandson, Sten, who still lives in New Orleans.

Last year, 2013, I was able to give an induction speech for Robert at (UWA) the University of West Alabama to honor him into the “Black Belt Hall of Fame” alongside George Washington Carver and others at that institution where I had served under Robert Brown in the Teacher Corps in 1968.

My induction speech used the “metaphor” of “What is PARAMOUNT in our field of Education?” as it was Robert who led a “protest” to have the name of the Black Greene County high school changed to “Paramount High School.” It had previously been named, “Greene County Training School” as were all Black County high schools for African Americans in that region during Jim Crow. The name was chosen to honor Martin Luther King, Jr., who in his last sermon/speech that year he was killed he spoke of – “Going to the Mountain Top!”

Thus, “PARAMOUNT” was chosen to re-name Greene County High School.

If you travel North on I-59 from New Orleans to Tuscaloosa and Birmingham, you’ll see the sign for “Paramount High School” just past Livingston, Alabama.

To learn about Dr. Robert Brown’s induction and place in Education History-

Google: Dr. Robert Brown, UWA, Black Belt Hall of Fame

A final word:

I just learned this morning, personally, that “freed” African Americans “ were the origination of the First Memorial Day Celebration. It occurred when (former) slaves honored troops who were killed while trying to fee them.

A photograph of the celebration in S. Carolina (1865) is posted if you Google:

The Blue Street Journal/ Know your History: Memorial Day

LikeLike