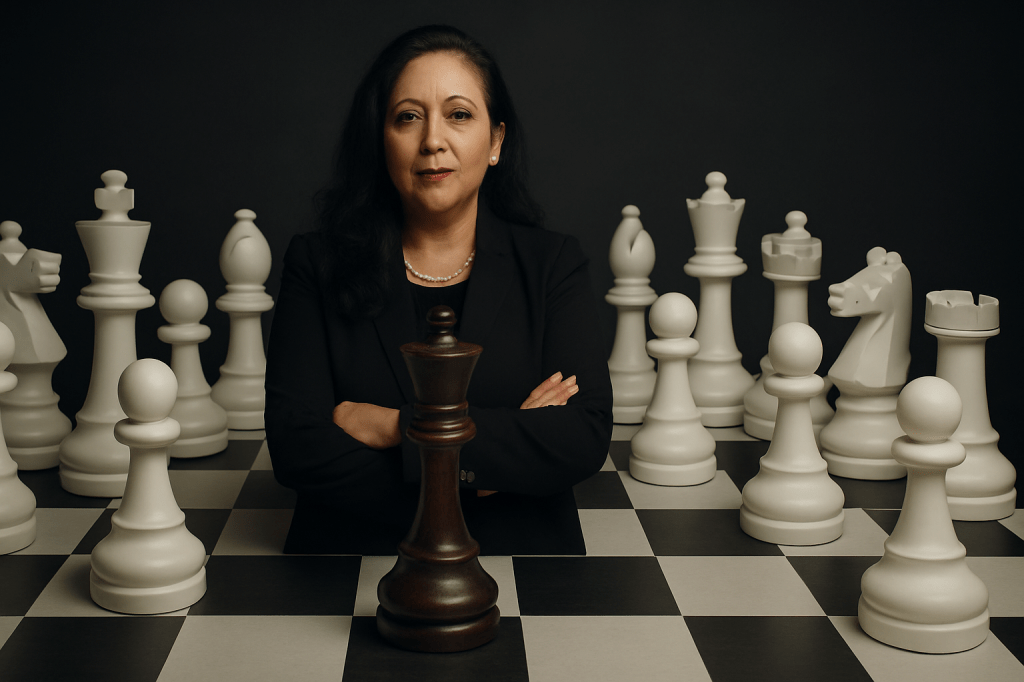

The recent removal of Dean Frances Contreras from her position as the first Latina dean of the UC Irvine School of Education has sparked a wave of concern across the higher education and civil rights communities. Her case appears to be more than a personnel decision based on current public information—it is a deeply troubling example of a recurring pattern in academia: leaders of color being punished for leading with integrity and courage.

Despite a strong record—elevating her school’s national rankings, securing tens of millions in funding, expanding access for students, and advancing innovation—Contreras was abruptly removed. Civil rights organizations, Latinx faculty, and national leaders are now demanding an independent investigation, citing a pattern of bullying, retaliation, and discriminatory treatment in response to her efforts to expose violations of university policy, state law, and basic ethical standards.

Her story is not unique.

Across the country, educational institutions often celebrate the appointment of leaders of color—but what happens when those leaders challenge entrenched power structures? When they prioritize equity over comfort? When they call out misconduct rather than ignore it?

What too often follows is a familiar cycle: praise becomes suspicion, support turns to silence, and bold leadership is rebranded as problematic.

This post explores that reality through the lens of what’s long been called the “uppity minority”—a term historically used to demean Black Americans who defied subservience, and is now resurfacing in coded ways to undermine leaders of color who dare to disrupt the status quo.

Let’s be clear: this isn’t about one institution or one leader. It’s about a system that desires diversity on paper but punishes those who lead with purpose. It’s about what happens when courage meets power—and power strikes back.

Let’s talk about the uppity minority.

If you’ve been a person of color in executive leadership—particularly in education—you already know what I mean. The term has deep historical roots, forged in racism, and flung like a dagger at anyone who dared to question the established order while Black, Brown, Indigenous, or “other.” And in today’s K–12 and higher education systems, the idea of the “uppity minority” is still very much alive—not always spoken, but present in evaluations, backchannel conversations, anonymous feedback, 360 evaluations, and leadership ousters that “just didn’t work out.”

In modern academia, the term has evolved. It now lives coded in phrases like:

- “Not a good cultural fit.”

- “A bit too vocal.”

- “Needs to be more collaborative.”

- “Made some people uncomfortable.”

- “More of an advocate than an executive leader”

- “Couldn’t do their job”

Let me decode that: it means you challenged power and institutional norms—and that made someone(s) uncomfortable.

This post is for every education leader who’s been told to “sit down and be grateful,” to smile more, to pick their battles, to be palatable, to “go along to get along.” But also, it’s a warning: We cannot change education systems while protecting the feelings of those who uphold their inequities.

The Contradiction: Wanted, But Only If You’re Quiet

Institutions love to recruit diverse leaders—it looks good in press releases. It’s a signal to donors, students, and politicians that “we’re making progress.” But too often, the real message is: “We want your face, not your voice.”

You’ll be celebrated in your hiring announcement. Your credentials will be applauded. Your lived experience will be marketed as a strength. But the moment you challenge the status quo—whether it’s in opposing administrative decisions about student protests, naming systemic racism, defending DEI, or backing marginalized faculty—the applause stops.

Suddenly, you’re “divisive.”

Suddenly, you’re “too political.”

Suddenly, you’re “not team-oriented” or accused of “spying” or being “confrontational.”

What happened? You became the one thing some institutions fear most: a leader of color who refuses to perform gratitude while injustice persists.

This contradiction is baked into how too many educational institutions function: they want diversity without disruption, equity without discomfort, and leadership without truth.

What “Uppity” Really Means in 2025

Let’s name it for what it is: “uppity” is a control tactic. It is how racialized systems discipline people of color who won’t conform to the unspoken rules:

- Don’t speak too passionately.

- Don’t correct misinformation.

- Don’t challenge traditions.

- Don’t organize around equity in ways that shift power.

It’s about tone-policing and hierarchy preservation. In this context:

- A white leader who disrupts is “bold” or “visionary.”

- A leader of color who does the same is “aggressive” or “not ready.”

This double standard isn’t accidental—it’s a feature, not a flaw. It’s how gatekeeping works. And it’s why we keep seeing cycles of diverse hires followed by swift departures, scandals, silence, or scapegoating.

The “uppity minority” label is a warning shot. It’s the institution saying: We invited you in, but don’t get too comfortable—and don’t you dare try to rearrange the furniture.

The Emotional Tax of Leading While Brown

Let’s talk about what this costs an uppity minority, not just professionally, but personally.

Being labeled as the “uppity” executive isn’t just political—it’s spiritual. It drains your energy, your faith, your joy. You feel isolated in decision-making rooms. You watch your ideas get ignored until someone else rephrases them. You experience gaslighting when your concerns are minimized. You carry the unspoken burden of representation while being denied the actual tools of change.

You try to lead with transparency, courage, and accountability. But what you face is:

- Silencing: You’re told not to respond publicly when you’re attacked.

- Retaliation: Your leadership is questioned, surveilled, or undermined.

- Erasure: Your legacy and impact are downplayed or rewritten.

Many came into leadership or faculty roles to uplift communities, to redesign systems for justice. But instead, people of color must survive systems designed to expel us the moment we stop being convenient.

And let’s be clear: when we are removed, the institution often replaces us with someone who “brings calm”—which usually means someone who won’t make people uncomfortable with truth.

How Institutions Hide Their Retaliation

It rarely looks like overt racism anymore. It’s subtler:

- The anonymous survey that “raises concerns about your leadership style.”

- The board member who says, “You’re too focused on race.”

- The press release that frames your departure as “mutual.”

- The offer of a “soft landing”—if you just go quietly.

Meanwhile, no one names the real reason you were targeted: you told the truth out loud.

And in a time when truth itself is politicized, truth-tellers of color are the first to be punished and the last to be protected.

Flipping the Script: From Uppity to Unapologetic

Here’s the truth: we need more uppity minority leaders.

We need leaders who:

- Name the systems, not just the symptoms.

- Build pipelines for equity, not just publicity.

- Defend students, faculty, and staff from political overreach.

- Refuse to sell out for safety.

- Know when to compromise—and when to call out cowardice.

The goal of education leadership should not be popularity. It should be purpose. And purpose requires spine. If speaking truth gets us labeled “uppity,” then maybe “uppity” is the leadership trait we need most in this moment.

Redefining Leadership: Preparation, Protection, and Political Courage

So what do we do?

Let’s redefine what leadership looks like in education.

Let’s build pipelines that don’t just place people of color in leadership roles—but prepare, support, and protect them.

Let’s stop mistaking comfort for institutional stability.

Let’s train boards, regents, and hiring committees to value courage and to recognize when leaders have been punished for showing that courage.

Because the issue is not just recruitment. It’s retention. Resilience. Reparation.

You can’t claim to value equity and then eliminate the very leaders advancing it when they make you uncomfortable.

If you’re not willing to defend leaders when they do the hard things—like challenge systemic problems, protect academic freedom, or defend student protest—then you are not committed to equity. You’re committed to comfort.

Collective Action and Solidarity

This is not a solo fight.

We need:

- Coalitions of conscience—leaders across race and role who will speak out when one of us is targeted.

- Faculty senates and student bodies who understand that institutional memory is short—and that history repeats unless it’s resisted.

- Search firms and consultants who stop reinforcing the idea that “safe” equals silent.

- Professional associations that track and report when leaders of color are ousted under suspicious or disproportionate scrutiny.

And we need media and public scholars to keep the receipts.

Because the pattern is clear. And if we don’t document it, defend against it, and disrupt it, the next generation of “firsts” and “onlys” will walk into the same trap we did.

Final Word

To every “uppity” Black, Brown, Indigenous, Asian, immigrant, and intersectional leader who’s been told to sit down, be grateful, or go away:

You are not a problem. You are the spark.

You are the fulfillment of your ancestors’ wildest dreams—and their boldest acts of resistance.

You don’t need to shrink to survive.

You don’t need to apologize for excellence.

You don’t need to lead quietly to be effective.

The future of education doesn’t need more figureheads.

It needs freedom fighters with office keys.

So stay “uppity.” Stay visible. Stay committed.

Because the moment we go quiet is the moment they win.

And remember: not all skin folk are kin folk.

Some will side with power over principle.

Some will weaponize proximity to power to maintain their access while undermining yours.

Stay grounded in values, not titles. In justice, not just affiliation.

We are not here to blend in. We are here to break through.

Please share this article.

Leave a reply to The Uppity Minority: You Spoke Up—So They’ll Call a Lawyer – Cloaking Inequity Cancel reply