In the whirlwind of daily commitments, policy debates, and the urgent push for educational equity, I rarely pause to look back. But every so often, there’s value in reflection. Recently, I took a look at the most-read and most-cited articles I’ve published over the years, and I was filled not with pride, but with profound gratitude—for the collaborators, communities, and questions that shaped this work, and for the readers and scholars who have found these ideas useful in their own advocacy and inquiry.

Scholarship, for me, has never been an abstract exercise. From the beginning, I’ve viewed research as a tool for change—an opportunity to elevate voices, challenge systems, and translate complexity into clarity. That orientation hasn’t always aligned with traditional academic incentives. But it has aligned with my heart, and with the communities I care about.

With that spirit in mind, I’d like to share a few reflections on some of my most-read pieces, most of which are now available in full on Academia.edu. These articles represent more than citation counts or download stats—they represent a body of work grounded in the belief that education can and should be a force for justice.

Does Teacher Preparation Matter? Yes, It Still Does.

(Co-authored with Linda Darling-Hammond, Daniel Holtzman, and Su Jin Gatlin)

This article remains my most cited work, with nearly 2,000 citations and countless references in the ongoing debates about alternative certification and teacher quality. The question was simple, but politically loaded: Does teacher certification matter for student achievement?

The data said yes. Teacher preparation, particularly in content and pedagogy, was significantly correlated with student learning outcomes. Teach For America and other fast-track programs were popular in policy circles—but the research didn’t support the hype.

I’m grateful for the opportunity to have contributed to this landmark study early in my career. It shaped my approach to scholarship: rigorous, comparative, and unapologetically relevant.

Accountability, Texas-Style: What Happens to Students Under High-Stakes Testing?

(Co-authored with Linda Darling-Hammond)

In 2008, we published this piece in Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis to examine how high-stakes accountability systems were impacting urban minority students in Texas. The findings were sobering: while test scores rose for some, the gains were often illusionary—driven by exclusionary practices, dropout rates, and reclassification games.

This article was one of the first empirical cracks in the ed reform façade. It showed how accountability policies, rather than lifting all boats, were often designed to reward systems—not students. Looking back, I remain proud of this piece because it changed the way policymakers and practitioners looked at the costs of test-based reform.

The Illusion of Inclusion: Race, Standards, and Critical Race Theory

Co-authored with Kofi and Amanda Brown, The Illusion of Inclusion examined how race was (and wasn’t) represented in state standards. Using critical race theory as a lens, we analyzed curricular language and found that many standards documents effectively erased the structural and historical realities of communities of color.

The response to this article was immediate and widespread. Published in Harvard Educational Review, it became a go-to reference for educators and curriculum designers looking to understand the deep connections between equity and standards. It also taught me the power of interdisciplinary frameworks—and the importance of naming the things many are unwilling to say out loud.

Teach For America: A Return to the Evidence

Few topics have generated more sustained interest—and more sustained critique—than Teach For America. I’ve written and co-authored several pieces examining the program’s outcomes, assumptions, and expansionist tendencies. The research speaks for itself: while TFA members often bring passion and energy, the data doesn’t support their superiority claims, especially in high-need schools that demand deep pedagogical knowledge and long-term commitment.

These articles, particularly Teach For America: A Review of the Evidence and A Return to the Evidence, received a wide readership. But more importantly, they informed local school board decisions, university partnerships, and even state policy discussions. That’s what research should do.

From Dewey to No Child Left Behind: The Erosion of Arts Education

Sometimes, it’s the unexpected topics that leave a mark in the field. In From Dewey to NCLB, my co-authors and I explored how the arts—long a cornerstone of holistic education—had been sidelined in the era of accountability. Published in Arts Education Policy Review, this article examined how standardized testing not only narrowed the curriculum, but erased entire disciplines in schools serving low-income communities and students of color.

What made this article special was the intersection of policy, practice, and cultural identity. It reminded me—and hopefully others—that education isn’t just about math and reading scores. It’s about humanity, expression, and joy.

Separate and Unequal: Special Populations in Charter Schools

In collaboration with Jennifer Holme and others, this legal-policy analysis examined how charter schools were—and often still are—segregating students with disabilities, English learners, and other special populations. Published in the Stanford Law & Policy Review, the piece unpacked how exclusion can be baked into school design, even under the guise of “choice.”

I’ve returned to this theme in many other articles, including Is Choice a Panacea? and The More Things Change, The More They Stay the Same. These works reflect my ongoing concern with how privatization strategies often replicate or worsen the inequities they claim to fix.

On my Colleagues

It’s deeply humbling to see these articles cited and shared by educators, policymakers, and fellow researchers. But none of this work has been solitary. At every stage of my scholarly journey, I’ve had the immense privilege of collaborating with some of the most brilliant, justice-driven minds in the field—Linda Darling-Hammond, Linda McNeil, Linda Tillman, Michelle Young, Muhammad Khalifa, and so many others. Each of them brought not only intellectual rigor but also a deep moral clarity to the work. They challenged me, inspired me, and helped shape a body of scholarship rooted in both courage and care.

These collaborations have been the heartbeat of my research—reminding me that writing for change is most powerful when done in community. I’ve also been fortunate to learn from graduate students, community leaders, and classroom teachers who kept the work grounded in lived experience and daily struggle.

Why I Still Love Writing

Academia can be isolating. It’s easy to get caught up in metrics, silos, and the slow pace of institutional change. But for me, writing has always been a joy. A release. A way of making sense of the world and contributing something useful to it.

Whether drafting a peer-reviewed manuscript, a magazine article, op-ed, or a blog post here on Cloaking Inequity, I approach each piece with the same questions: Who needs to hear this? Who is being left out? What truth needs telling?

That mindset has guided every paragraph I’ve ever published. And it’s what keeps me going, even on the hard days.

Looking Ahead

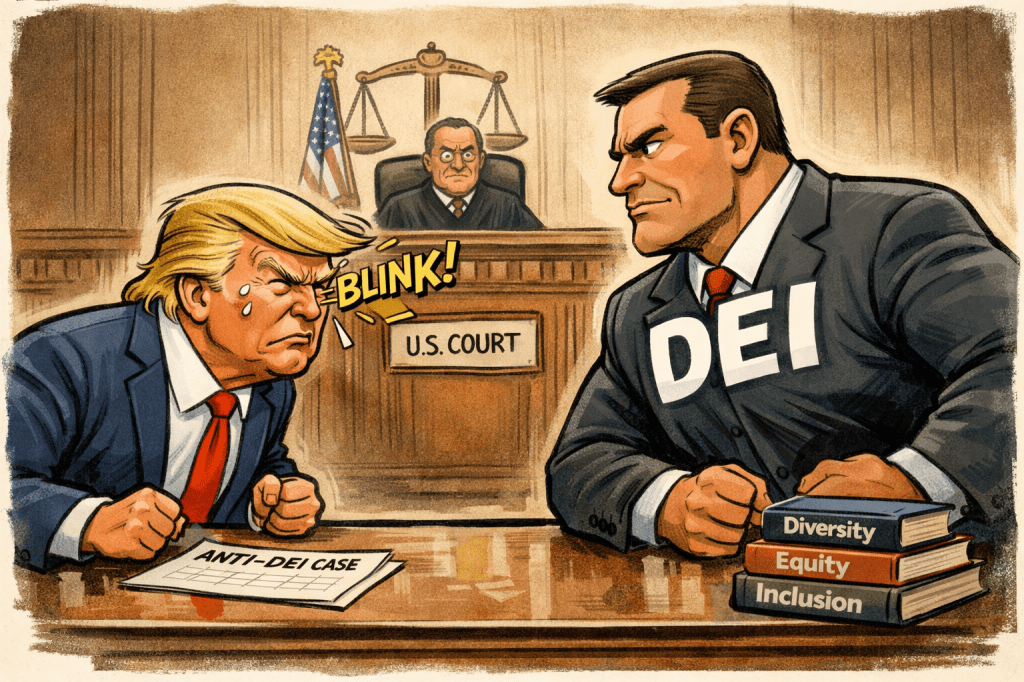

As I write this, the challenges facing public education are immense. Political polarization, censorship, attacks on DEI, and funding instability threaten to reverse decades of progress. Yet I remain hopeful—because I’ve seen what’s possible when scholars, communities, and policymakers come together with courage and clarity.

I intend to keep writing, mentoring, speaking, and pushing. There are still so many stories to tell, so many policies to unpack, and so many leaders—especially new faculty and students—to lift up.

To those who’ve read my work, cited it, challenged it, or shared it: thank you. Your engagement gives these ideas life beyond the page.

And to those discovering these articles for the first time, I invite you to explore them on Academia.edu. More than anything, I hope they serve as tools for your own advocacy, leadership, and reflection.

Because in the end, scholarship is not about the scholar. It’s about the work—and the world we hope to shape through it.

Like a Picasso painting, the work of justice in education is not always linear or easy to interpret at first glance. It is textured, layered, fragmented, and bold. It reveals its meaning over time, through angles of light, lived experience, and courageous reassembly. In this Cubist canvas we call public education, each article, each classroom, each student is a vital stroke of color—part of a larger portrait still in progress.

Let us keep painting.

References

Leave a comment