When UC Berkeley scholar Travis J. Bristol speaks of a “second nadir” in U.S. race relations, he invokes a chilling historical echo. The first nadir followed the end of Reconstruction—when the Ku Klux Klan rose, lynchings of Blacks was commonplace, and Plessy v. Ferguson enshrined “separate but equal” into law. Today, Bristol argues, we are experiencing a new nadir. And it is not accidental.

“The nadir” and “second nadir” are not my ideas or my words. I’m just agreeing that we’re living in this second wave of the lowest point of race relations since the end of chattel slavery in the United States.” — Travis J. Bristol

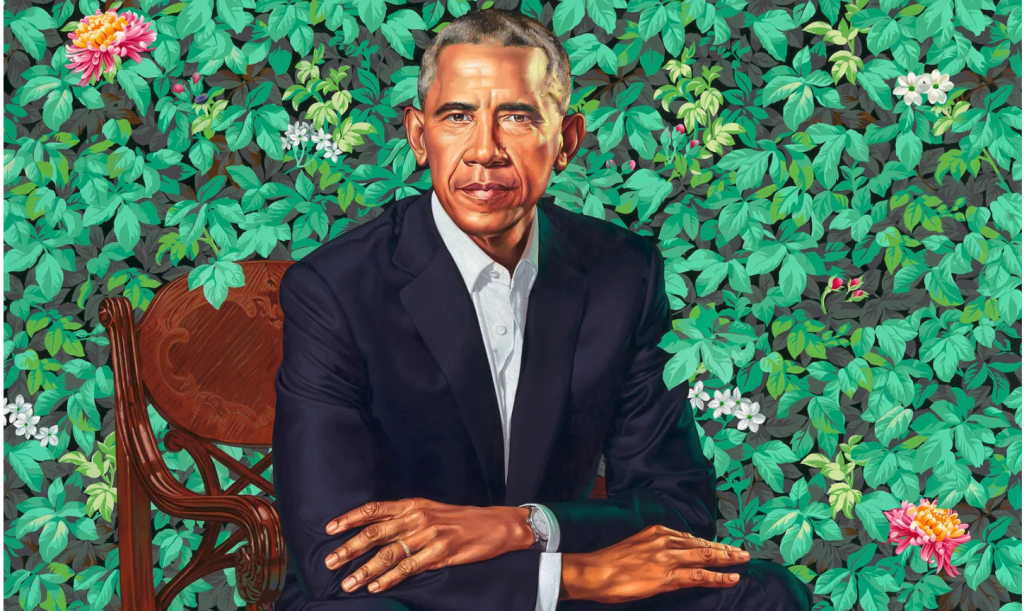

Bristol traces this nadir back to a moment that many of us celebrated: the election of Barack Obama. The irony is brutal. The ascendance of a Black president symbolized long-fought progress, yet it also ignited fierce backlash—birther conspiracies, coded attacks on Black legitimacy, and eventually the overt racial grievance politics that fueled Donald Trump’s rise. In that backlash, he argues that the old racial order has sought to reassert itself, seeking to remind America that advancement for historically marginalized people is fragile, temporary, and contested.

Engineered Division

That we are at this low point is not the outcome of coincidence, but of strategy. Political actors have long recognized that race is one of the most powerful tools for mobilizing fear and resentment. From “law and order” rhetoric in the 1970s to “Make America Great Again” in the 1980s and now, the formula has been refined: sow racial anxiety, link it to economic precarity, and profit from division.

It is no accident that racialized voter suppression laws have resurged. It is no accident that educational funding and opportunity has been rolled back while Confederate monuments, names and symbols are defended as “heritage” despite representing the history of racial oppression and treason. It is no accident that Black educators, whose research and classroom practice demonstrate measurable benefits for Black students and for all students, are being driven out of teaching just as their value becomes undeniable. This is the manufactured second nadir.

Black Teachers at Risk

Bristol’s research highlights a paradox. In the past two decades, the number of Black teachers entering classrooms increased, thanks to deliberate recruitment and equity efforts supported in public policy and primarily executed by colleges and universities. According to Bristol, the presence of Black teachers is transformative: Black students in their classrooms are more academically successful, less likely to be suspended, and more likely to enroll in honors courses. White and Latinx students also benefit from higher expectations and richer perspectives.

And yet the proportion of Black teachers has declined—from 8.6% in 1990 to 6.1% in 2020. Many leave not for lack of passion, but for lack of support, fair pay, and sustainable conditions. Too often they are placed in the hardest-to-staff schools with little institutional backing, expected to be disciplinarians, cultural translators, and emotional anchors without corresponding resources. One study Bristol cites found that 41% of Black teachers would leave for a higher-paying job, compared to 34% of white teachers. Another line of research shows that Black teachers often face hostile work environments where their expertise is questioned, their curriculum choices are second-guessed, and their disciplinary decisions are scrutinized through racialized lenses.

Attrition is not simply about dollars and cents; it reflects the political economy of race in education. As Travis Bristol and other scholars argue, Black teachers are frequently recruited as “role models” for Black students, yet they are rarely given the same opportunities for advancement, leadership, or professional respect as their white peers. Data from the Learning Policy Institute confirms that teachers of color, especially Black teachers, experience higher turnover rates not because they are less committed but because they encounter greater stress, fewer supports, and inequitable working conditions. At precisely the moment that data validates the necessity of Black teachers—their positive impact on student achievement, discipline, and aspirations—they are being pushed out.

This is not just unfortunate; it is systemic. It reveals how schools simultaneously acknowledge the value of Black teachers while failing to create the environments in which they can thrive. The result is a pipeline that leaks at every stage: barriers to entry through licensure exams and biased hiring, marginalization once in the classroom, and burnout that leads too many to leave. The crisis is not a failure of Black teachers. It is a failure of the system to honor, support, and sustain them.

After the Awakening: George Floyd and Black Lives Matter

The murder of George Floyd in 2020 forced millions of Americans to confront racial injustice in ways that could no longer be ignored. Streets across the nation filled with protestors demanding accountability, transparency, and transformation. Corporations pledged billions toward racial equity. Universities issued public commitments to diversify faculty and confront their own complicity. Many spoke of a “racial reckoning.”

For a moment, it seemed like the tide might be shifting to a more accepting society. But the backlash came quickly, and forcefully. What Bristol calls the “second nadir” hit us in the face, like a pendulum swinging back harder after being pulled in the other direction. Anti–Critical Race Theory bills swept through state legislatures. Books about Black history were pulled from shelves. Teachers faced gag orders on how they could discuss race, identity, or even slavery.

The movement that sought to name and repair injustice was recast by politicians as a threat to White America. Those who marched for justice were caricatured as dangerous. Black teachers, often the very people positioned to carry forward lessons from this “awakening”became lightning rods for political attacks. The paradox is striking: in the wake of a global demand for racial justice, the institutions best equipped to nurture it, the classroom and its teachers, are under siege.

A Historical Throughline

The story of Black teachers in America has always been one of resistance against systemic odds. In segregated schools of the Jim Crow South, Black teachers nurtured excellence so their students could one day compete in an integrated society. They built rigorous, culturally sustaining classrooms in the face of institutional hostility.

That tradition continues today, but in an era of politicized culture wars, the pressure is immense. Black teachers find themselves targeted for simply telling the truth about history, for affirming the humanity of Black children, for refusing to shrink in the face of censorship. The very qualities that make them indispensable, honesty, cultural responsiveness, and high expectations, are now recast as liabilities by political forces intent on rewriting the narrative.

Choosing What Comes Next

We are indeed living through a nadir, and history tells us it will not last forever. But whether the pendulum swings forward or backward depends on collective will. Will we allow racial division to be continually engineered as a political tool? Or will we recognize that the struggle for equity requires not just naming injustice, but sustaining those who stand on the front lines—our Black teachers, our community leaders, our truth-tellers?

This moment is not just about classrooms, but about democracy itself. The same forces pushing Black teachers out of schools are the forces rewriting history, limiting access to the ballot, and stoking racial resentment for short-term political gain. If the second nadir has been engineered, it can be dismantled. But only if we confront its architects, defend the educators and communities under attack, and build anew. Because when Black teachers leave, we don’t just lose professionals, we lose a vital counterweight against the politics of division. We lose a piece of democracy we must claim and cherish.

Julian Vasquez Heilig is a nationally recognized policy scholar, public intellectual, and civil rights advocate. A trusted voice in public policy, he has testified for state legislatures, the U.S. Congress, the United Nations, and the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, while also advising presidential and gubernatorial campaigns. His work has been cited by major outlets including The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Los Angeles Times, and he has appeared on networks from MSNBC and PBS to NPR and DemocracyNow!. He is a recipient of more than 30 honors, including the 2025 NAACP Keeper of the Flame Award, Vasquez Heilig brings both scholarly rigor and grassroots commitment to the fight for equity and justice.

Leave a comment