Every September, Hispanic Heritage Month invites us to honor the cultural contributions and enduring wisdom of the Spanish-speaking world. Among the most lasting gifts is the literature of Miguel de Cervantes, whose Don Quixote, published more than four centuries ago, remains one of the most influential novels ever written. Cervantes gave us unforgettable images of imagination, folly, and persistence: a noble knight mistaking windmills for giants, tilting his lance against illusions. That story, born in Spain but embraced around the globe, reminds us how narratives travel across centuries and borders, shaping how we understand human behavior and politics.

Since Miguel de Cervantes released Don Quixote in 1605, readers have laughed for hundreds of years at the image of a would-be knight galloping furiously at windmills, convinced they were giants. The scene was comic genius: rusty armor, a noble steed that looked more like a tired mule, and a hero charging at wooden sails that only spun faster with every thrust. Yet beneath the humor was a serious insight: humans often waste their strength fighting enemies that exist mostly in their own heads. “Tilting at windmills” became shorthand for battling illusions, and the phrase has never lost its bite.

Fast-forward four centuries and, oddly enough, the windmill still hasn’t caught a break. The Don Quixote of today isn’t a deluded nobleman on horseback but Don Trump at a podium, railing against turbines as if they were plotting global conquest. The rhetoric is passionate, dramatic, and, let’s be honest, still downright funny. At times it sounds less like energy policy and more like Cervantes’ novel brought to life.

Take this declaration from Don Trump about them: “It is the worst form of energy, the most expensive form of energy, but windmills should not be allowed.” That’s not a punchline from Monty Python. It’s a serious statement. Cervantes might have blushed with pride: four hundred years later, an American presidents is still charging against windmills with the same fervor as his knight errant.

The attacks don’t stop there. A Don Trump promise: “We will not allow a windmill to be built… they’re killing us.” Killing us! Picture for a moment a 200-foot turbine sneaking into your backyard like a Scooby-Doo villain. It is almost too perfect an echo of Quixote shouting, “Giants! Giants!”

Don Trump’s imagery becomes even more cinematic: “You see these windmills all over the place, ruining your beautiful fields and valleys and killing your birds, and if they’re stuck in the ocean, ruining your oceans.” In one sentence, the poor turbine is transformed into an ecological menace, a vandal of valleys, and a pirate of the high seas. Cervantes would have applauded the plagiarism. If he were alive today, he might even sue for royalties.

Don Trump’s list of grievances goes on with admirable thoroughness: “It kills the birds, ruins the look, they’re noisy… If you see them from your house, your house is worth like 50 percent or more less… In every way, it’s bad.” Note the Quixotic rhythm here: keep piling on reasons until ordinary machinery begins to look like an apocalyptic threat. Quixote thought he was defending the honor of ladies; today’s critic is defending property values. Different era, same silly energy.

Then comes Don Trump’s grand flourish: “Windmills are ruining our country, they’re ruining everyone.” Not just inconveniencing us—ruining everyone. That’s a lot of damage for a machine that looks like a giant pinwheel. Quixote once believed windmills threatened the very future of chivalry. It seems the tradition lives on.

And for the encore, we get the all-caps social media rant: “STUPID AND UGLY WINDMILLS” are responsible for high energy prices, electricity shortages, whale deaths, bird deaths, environmental devastation, and even cancer. You almost expect a footnote blaming them for Houston traffic jams, cement porch stubbed toes, and the cancellation of The Apprentice. Cervantes, if he were editing his thoughts, might suggest tightening the prose, but only after he stopped guffawing.

What makes this all so “Quixotic” is not just the content but the level of nonsense. Like the knight of La Mancha, the speaker turns ordinary objects into villains through sheer force of imagination. A barber’s basin became the Golden Helmet of Mambrino. Peasant girls became noble ladies. Windmills became giants. In our age, turbines morph into serial killers of birds, destroyers of oceans, and harbingers of national collapse. It’s the same transformation, just with modern props.

Humor aside, there’s a deeper lesson. Cervantes wasn’t writing about windmills per se; he was writing about obsession. Quixote needed enemies to justify his role as a knight. Without monsters, there was no quest. In the same way, railing against turbines isn’t really about energy—it’s about Don Trumps constant need for a visible villains. The windmill becomes a stage prop, something to attack with gusto so the audience can cheer.

There’s also the question of performance. Don Quixote had Sancho Panza trailing behind him, bewildered but loyal, and a host of villagers watching with a mix of pity and amusement. Today’s anti-windmill crusades are also staged: microphones, cameras, headlines, Fox News and social media echo chambers. The windmill is less an energy source than a backdrop for left wing drama. It provides scale, literally towering, against which the speaker can appear heroic.

The modern crusader against windmills is seen by followers as bold, unafraid to shout what others only whisper. To supporters, railing against “stupid and ugly windmills” isn’t absurd at all, it’s courage. To critics, it looks like jousting with pinwheels.

So where does that leave us? The original lesson of Cervantes still stands: when we spend our strength battling illusions, we miss the real giants, usually on purpose. The problems that demand attention—climate change, the economy, unprecedented technological transition—don’t vanish because we’ve declared war on spinning blades. In fact, Don Trump obsessing over imaginary foes and stupid makes our nation less prepared for the real challenges.

Cervantes, like many of us today, would likely chuckle and then cry. He might even write a sequel: Don Quixote 2.0: The War on Wind Turbines. In it, the knight would swap his horse for a podium, his lance for a microphone, and his armor for a suit and tie. The giants haven’t changed, only the costume of the man charging at them.

The truth is, giants don’t live in fields or oceans. They live in Don Trump’s political strategy and machinations—summoning fear, sustained by obsession, and given life by constant repetition. The windmill remains what it has always been: a machine turning in the breeze. The fight is not against windmills but against the lies that make them giants.

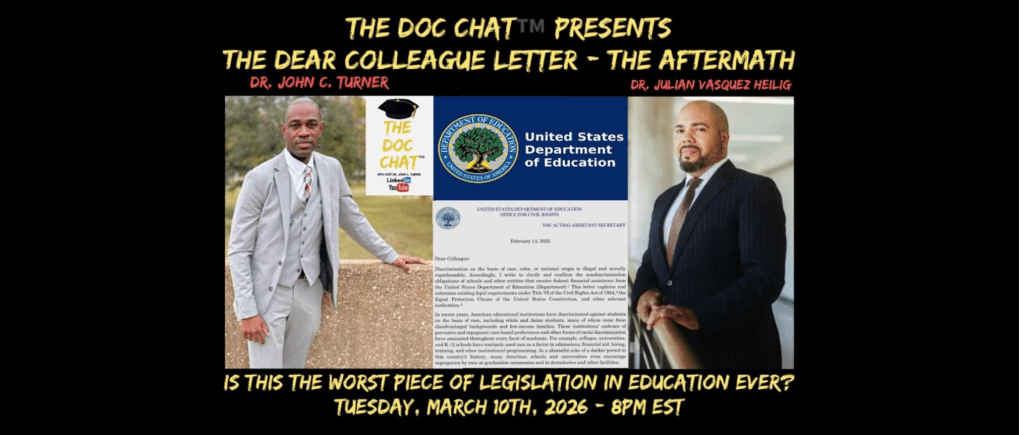

Julian Vasquez Heilig is a nationally recognized policy scholar, public intellectual, and civil rights advocate. A trusted voice in public policy, he has testified for state legislatures, the U.S. Congress, the United Nations, and the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, while also advising presidential and gubernatorial campaigns. His work has been cited by major outlets including The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Los Angeles Times, and he has appeared on networks from MSNBC and PBS to NPR and DemocracyNow!. He is a recipient of more than 30 honors, including the 2025 NAACP Keeper of the Flame Award, Vasquez Heilig brings both scholarly rigor and grassroots commitment to the fight for equity and justice

Leave a comment