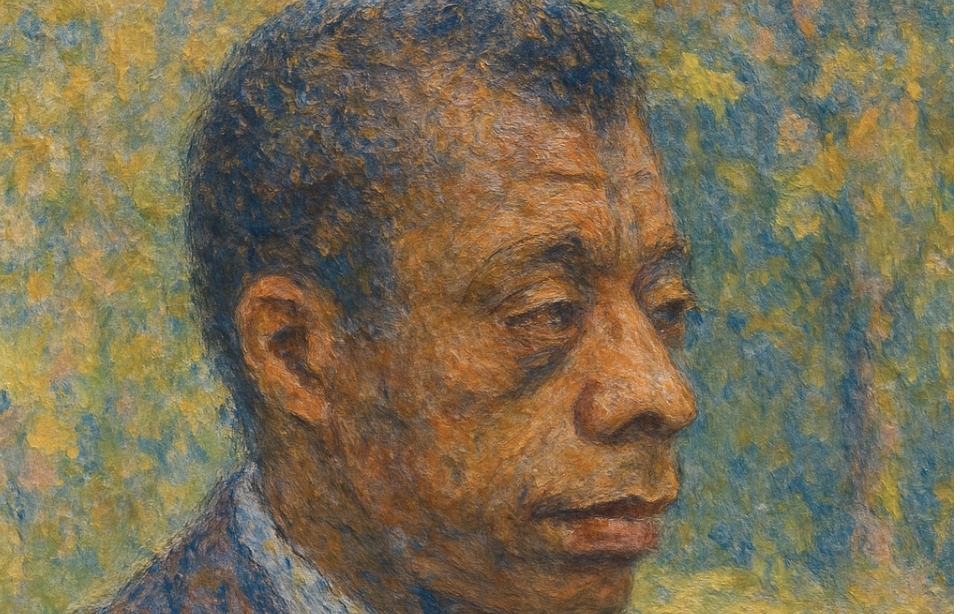

“We are living through a very dangerous time.” James Baldwin began A Talk to Teachers with those words in October 1963, addressing a group of New York City educators just weeks after some of the most searing events of the civil rights era. That year, Medgar Evers was gunned down in his driveway by a white supremacist in Jackson, Mississippi. That year, four little girls—Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley—were murdered when the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham was bombed by Klansmen. That year, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. Baldwin was speaking into a maelstrom.

As Clint Smith reminded readers in The New Yorker, Baldwin’s words still burn with relevance. Our own time is fraught with violence, immigration crackdowns, and culture-war battles waged in classrooms. Smith draws a straight line from Baldwin’s “dangerous time” to today’s return to school after summers of turmoil—Charlottesville’s torch-lit marches, the rolling back of DACA protections, and policies that deepen division rather than dismantle it.

And now we must grapple with a further descent: the toxic spectacle surrounding Charlie Kirk. His shooting and its aftermath have been weaponized into another culture-war circus, one that risks distracting us from the deeper truths Baldwin was trying to name. Kirk built a career manufacturing outrage, distorting concepts like free speech, and vilifying educators and students alike. The irony is stark: a man who spent years fueling division has now become a martyr in narratives that only inflame it further. The result is a public discourse trapped in reaction, outrage, and distortion—exactly the kind of dangerous time Baldwin warned us about.

Children See What’s Happening

Smith’s New Yorker piece tells of a D.C. elementary teacher whose students asked after Charlottesville, “Why was somebody so angry that they wanted to drive a car through people who were asking for their rights?” These are not abstract political questions—they are children trying to make sense of a society that promises liberty but delivers violence. Their teacher did what Baldwin urged: he created space. He sat them in a circle. He let them ask. Later, he brought them to a vigil for Heather Heyer, who was killed by that car. The children spoke, and one student said afterward: “People wanted to listen to me.” Baldwin’s insistence that young people must learn the world belongs to them was realized in that moment.

Baldwin argued that education is always political. He wrote that Black children grow up with two contradictory messages: the Stars and Stripes waving triumphantly overhead while textbooks, policies, and neighbors tell them they have contributed nothing to civilization. The Zinn Education Project emphasizes this paradox, noting that education at once liberates and constrains, awakening consciousness while attempting to police it (Zinn Education Project). Baldwin insisted that slavery was no “accident” but “a deliberate policy hammered into place in order to make money from black flesh.” Because America never faced this truth, he warned, “we are in intolerable trouble.” That trouble is clearly not only historical—it is contemporary in 2025.

A Blueprint for Teachers

Smith reflects in The New Yorker that when he was a young teacher, he often stuck to the book. He drilled grammar, pursued standards, and prepared students for exams. Meanwhile, his students were losing friends to gun violence, and the killing of Trayvon Martin hung unresolved. He kept politics at the periphery because test scores determined his evaluation and job security. Then a veteran teacher handed him Baldwin’s essay, and it shifted everything. He realized that rigorous academics and culturally relevant teaching are not opposites. Julius Caesar could sit alongside conversations about community violence. Ellison’s Invisible Man could frame immigration debates. Baldwin gave him permission to see teaching not as neutral, but as deeply engaged with life beyond the classroom.

This insight is reinforced elsewhere. WBUR’s Here and Now highlighted how Baldwin’s essay is regularly revisited in moments of crisis, reminding educators that silence in the classroom is itself political (WBUR). An essay at Philly’s 7th Ward cited Baldwin’s warning that teachers who confront racism will encounter “the most fantastic, the most brutal, and the most determined resistance,” a description that feels prescient in a time when anti-CRT laws and book bans dominate headlines and punishment for free speech criticism of Charlie Kirk dominates headlines.

Dangerous Then, Dangerous Now

Baldwin’s words compel us to ask: what does it mean to teach and live in a “dangerous time”? In 1963, the dangers were assassinations, bombings, and state violence against peaceful marchers—threats that remain all too familiar today. Now they also include children drilled in active shooter protocols, immigrant families terrorized by deportations, and educators attacked simply for naming racism or queer existence. As one mother in Washington, D.C., said at a community meeting cited in The New Yorker, “I’m tired of having to teach my two-year-old how to duck; I’m tired of having to teach my two-year-old that certain nights when we get home from school we have to sit on the floor.” That is Baldwin’s prophecy made real—the world surrounding children has been rendered criminal, and teachers are left to confront it with unflinching honesty.

In fact, the most quoted line from A Talk to Teachers is also its deepest challenge: “The paradox of education is precisely this—that as one begins to become conscious one begins to examine the society in which he is being educated.” Education is not simply about preparing students for jobs or tests; it is about awakening consciousness. It is about giving young people the tools to ask why their neighborhoods lack investment, why their schools are underfunded, why their histories are absent from textbooks, and why violence stalks their communities. For white students, it also means dismantling the myths of innocence and exceptionalism that Baldwin exposed with such clarity. This is what “woke” truly means: the courage to ask hard, critical questions about inequity and injustice. That is precisely why right-wing politicians rail against it—because such questioning lays bare both their policy failures and the deeper desires they would prefer remain hidden.

A Call to All Americans

Baldwin’s words compel us to ask: what does it mean to teach and live in a “dangerous time”? In 1963, the dangers were assassinations, bombings, and state violence against peaceful marchers—threats that remain all too familiar in America today. Now they also include children drilled in active shooter protocols, immigrant families terrorized by a militarized ICE , and educators attacked simply for naming racism or queer existence. As one mother in Washington, D.C., said at a community meeting cited in The New Yorker, “I’m tired of having to teach my two-year-old how to duck; I’m tired of having to teach my two-year-old that certain nights when we get home from school we have to sit on the floor.” That is Baldwin’s prophecy made real—the world surrounding children has been rendered criminal, and teachers are left to confront it with unflinching honesty.

So what do we do with Baldwin’s words now? First, we reject the pretense of neutrality. Every choice in education has become political, whether we admit it or not. Silence in the face of injustice is not neutrality—it is complicity. Baldwin warned that education either liberates or indoctrinates, and in this moment of national grief and anger, that choice has never been clearer.

Second, we must recognize that rigorous academics and social relevance go hand in hand. To teach Shakespeare without connecting it to questions of power, betrayal, or justice is to strip it of its vitality. To teach history without naming how oppression is constructed and resisted is to turn it into propaganda. Students deserve the truth, not a sanitized curriculum meant to appease the powerful.

Third, we must create space for student voice. Baldwin insisted that children must know the world is theirs to shape. That begins with knowing they are heard. In the aftermath of Kirk’s assassination and the waves of repression it has unleashed, from tighter surveillance of classrooms to the silencing of dissent, students see clearly that their futures are being negotiated in real time. Giving them the chance to speak, to analyze, to imagine alternatives is not indulgence; it is democracy in practice.

The New Yorker’s prescient retelling of Baldwin’s essay, alongside Clint Smith’s teaching journey, reminds us that what happens in classrooms can either replicate injustice or plant the seeds of liberation. Other sources, from WBUR to the Zinn Education Project, testify that Baldwin’s essay continues to inspire educators who refuse to separate teaching from justice. In today’s climate, when educators face harassment for naming racism, for affirming LGBTQ+ students, or simply for teaching history with honesty, Baldwin’s challenge is not academic—it is existential.

Conclusion

As 2025 enters fall, we do so in the shadow of a tumultuous reality. Americans are being hunted not for what they teach in the classroom, but for the words they speak in their spare time. The Vice President of the United States has called for Americans to be fired or disciplined simply for criticizing Charlie Kirk or the right wing more broadly. This weaponization of political power against freedom of speech is chilling, and it strikes at the heart of democracy itself.

In 1963, James Baldwin warned that “we are living in a very dangerous time.” He told teachers that their responsibility was not to produce conformity, but to help students examine the society in which they live. That prophecy reverberates across the decades. Then, Baldwin named white supremacy, political assassinations, and the bombing of children in churches. Today, the dangers manifest in the silencing of dissent, the rebranding of authoritarianism as patriotism, and the targeting of educators who dare to speak truth. The forms are new, but the threat is the same: a society that fears honest teaching because it fears honest reckoning.

Baldwin insisted that to teach honestly in such a moment was an act of resistance. That calling has never been more dangerous, never more unsafe, and never more urgent. To remain silent is to surrender to fear. And yet, there is hope. Every lesson taught with courage, every student encouraged to question, every community that rallies to defend truth-telling educators is a reminder that democracy is not dead—it is defended daily in our classrooms.

Baldwin’s charge to teachers in 1963 remains our charge now: to confront dangerous times not with retreat, but with clarity, compassion, and unflinching honesty. The world is watching. Our students are watching. And we must show them that even in danger, truth has a place, and that the classroom is still where liberation can begin.

Julian Vasquez Heilig is a civil rights advocate, scholar, and internationally recognized keynote speaker. He has served as Education Chair for both the NAACP California State Conference and the NAACP Kentucky State Conference, advancing equity for students and communities. Over the past decade, he has delivered more than 150 talks across eight countries, seeking to inspire audiences from universities to national organizations with research, strategy, and lived experience that move people from comfort to conviction and into action.

Leave a comment