Every fall, new waves of university rankings hit the headlines. Media outlets trumpet which institutions rose, which fell, and which managed to hold on to coveted spots at the top. Parents share the results, institutions market them, and high school students pore over the lists as they build their application strategies. Rankings season has become part of the culture of higher education.

But a recent LinkedIn post by Jeffrey J. Selingo, the author of Dream School, reminded me of something many of us inside higher education already know but rarely say out loud: “The incumbents in any culture who already have what you might want discourage the idea that we have agency.”

In higher education, those “incumbents” are the most selective colleges and universities. Their strategy for protecting their position is simple: encourage more students to apply, while refusing to expand incoming class sizes. The math works in their favor. A flood of applications and a static number of seats produces an ultra-low acceptance rate, which becomes a marketing tool. Families then take that exclusivity as a signal of prestige, even though it tells us nothing about the quality of education, mentorship, or student experience.

The Pretzel Problem

As the Dream School author discussed with Michael Smerconish on CNN, this prestige chase contorts families into impossible shapes. Too many teenagers twist themselves into pretzels to fit what they think selective colleges want: every AP class, every club, year-round sports, summer leadership programs, service projects, and anything else that might add a line to their résumé. The goal becomes not learning or growth but manufacturing a profile polished enough to catch the eye of a school that rejects more than 90 percent of applicants. I have lived intimately as a parent.

This is not just stressful. It is distorting. It narrows the definition of success to a handful of institutions at the top of a ranking and it teaches young people that their worth is tied to a letter from an admissions office. But as Dream School points out, there are hundreds of other colleges and universities where students can thrive. These are schools where balance is possible, where faculty mentorship is central, and where opportunities for research, internships, and engagement are real. They are not consolation prizes. They are communities where students graduate into good jobs, rewarding careers, and meaningful lives.

The book includes a fascinating statistic: fewer than 20 percent of parents said they personally cared about rankings. More than 60 percent admitted that their friends and community cared. Translation: the obsession with prestige often is not about what parents themselves want but about what the neighbors will think. It is about the bumper sticker on the back of the minivan or SUV: “My kid goes to [Insert Selective College Here].” That sticker becomes a symbol of pride, proof of belonging in a certain social circle. Families may not say it out loud, but the pressure is real. College choice becomes less about fit and more about social signaling.

Inside the Rankings Machine

From the outside, college rankings present themselves as neutral, objective measures of institutional quality. Parents, policymakers, and students often assume that a number beside a university’s name reflects careful analysis, a trustworthy shorthand for excellence. From the inside, however, the process looks very different. I know this because for the past six years I have served as a voter in both the QS World University Rankings and the U.S. News & World Report rankings. What I found was not rigor and nuance, but an exercise in simplification that often bordered on the absurd.

Each year, I was asked to rate hundreds of institutions on a simple scale, usually from one to five. That meant reducing enormously complex universities with distinct histories, missions, and student populations to a single digit. Think about that for a moment: how could one number possibly capture the difference between a flagship public university serving tens of thousands of first-generation students and a small liberal arts college devoted to intimate mentorship? How could it fairly weigh the global research output of a powerhouse institution against the transformative community impact of a regional university? The survey asked us to collapse nuance, texture, and lived reality into a single point on a scale. The results were later transformed into rankings that parents and students consumed as if they were gospel.

The pressure to influence those numbers was constant and unrelenting. Each fall, as the survey period approached, my office became ground zero for a flood of glossy brochures, curated marketing packets, and even small gifts sent by institutions eager to stand out. The goal was not subtle. Universities wanted to make sure they were top of mind when I sat down to complete the survey. My inbox filled with messages touting new programs or star faculty hires. My mailbox overflowed with photo-laden magazines, letters from presidents, and promotional material that blurred the line between information and lobbying. Rankings season felt less like an exercise in evaluating quality and more like a marketing blitz aimed at shaping my memory.

This dynamic raises a troubling question: what could universities achieve if all that time, money, and energy went into students instead of rankings theater? Many of the institutions sending me packages were resource-strapped. They could have used those funds for scholarships, faculty development, or expanding student support services. Instead, they invested in glossy reminders designed to nudge my vote. In some cases, a university’s place in the rankings hinged less on its actual educational quality than on how effectively it could insert itself into the minds of survey respondents like me. The reality says more about the rankings industry than it does about the substance of higher education.

The survey system itself was flawed from the start. It forced voters to simplify institutions that defy simplification. A single score could never capture the full range of what universities actually do: educate diverse populations, generate research, serve communities, and prepare graduates for life and work. Yet those simplified numbers carried enormous weight once they were aggregated. They shaped perceptions for families deciding where to send their children, for policymakers allocating resources, and even for employers judging the quality of degrees. The oversimplification of the rankings machine created ripple effects across the entire ecosystem of higher education.

The criteria that rankings reward tell their own story. Institutions are judged by test scores, endowment size, alumni giving rates, faculty publications, and research output. Selectivity is prized, so the fewer students a university admits, the more prestige it accrues. These measures privilege incumbents, the already wealthy and well-known institutions that can afford to be selective and resource-intensive. By contrast, universities that open doors to first-generation students, that serve regional economies, or that prioritize teaching and mentoring often find themselves penalized by the very system designed to measure excellence. Rankings reinforce the old hierarchies instead of challenging them.

This is where the critique becomes most urgent. Families consult rankings because they want assurance. They want to know their investment will pay off, that their children will have access to opportunity. But the rankings do not actually measure those outcomes. They measure inputs like opinions, test scores and endowment dollars. They measure exclusivity and wealth. They rarely measure how well a university supports first-generation students or whether graduates thrive after leaving campus. By emphasizing selectivity, they reward universities that turn students away, rather than those that expand access. That inversion of values is baked into the system.

Over time, the rankings machine distorts behavior across the higher education landscape. Universities learn to play the game. They allocate resources to raise SAT averages, to boost faculty publication counts, to manage acceptance rates strategically. In media we have seen reports that some even manipulate data outright, submitting inflated statistics on class sizes, financial resources, or alumni giving. The scandals that occasionally surface are not anomalies. They are the logical outcomes of a system that incentivizes appearances over substance.

The rankings process also creates perverse incentives in governance. Boards of trustees and university presidents at selective universities, under pressure from parents and alumni, set goals tied explicitly to climbing in the rankings. Fundraising campaigns promise to move institutions into the “top 50” or “top 25.” The rankings become a performance metric not just for universities but for their leaders. Success is measured not by how well an institution fulfills its mission but by how it compares to a shifting list produced by media companies. The distortion is systemic and powerful.

At its heart, this system reduces higher education to a market competition rather than a public good. Universities compete for prestige because prestige attracts applications, donations, and political influence. But in that competition, the deeper purposes of education: equity, civic responsibility, human development—fade into the background. The survey I filled out each year became one small part of that larger system. A single number from me contributed to rankings that shaped national debates. .

This is the inside of the rankings machine. It is overwhelming, reductive, and driven as much by perception management as by substance. It rewards institutions already rich in resources while marginalizing those doing some of the hardest, most important educational work in the country. It pressures universities to perform for voters rather than invest in students. And it asks evaluators like me to make difficult comparisons that erase the diversity and nuance of higher education. From the inside, it is clear: rankings are less about measuring quality than about reinforcing hierarchies.

The Honest Truth: I Felt the Pressure

I will be honest. When I served in senior leadership roles, I felt the pressure to improve rankings. No one ever ordered me to do it. But I understood that families and students pay attention to rankings, and those numbers influence not only individual choices but also institutional reputation. I also knew that rankings affect whether a student applies, whether a parent feels confident, and even whether an employer views graduates as desirable. I never saw rankings as the ultimate measure of success, but I could not ignore their power.

At Western Michigan University, we worked deliberately to improve outcomes that mattered, and hope that the rankings would reflected it. In the 2025 U.S. News Program Rankings, our undergraduate online programs climbed 32 spots, entering the Top 100 nationally for the first time in school history. Student engagement scores jumped 65 spots, and we moved up 20 places in the veteran ranking category. Graduate education online programs rose as well, securing a Top 12 position in Student Excellence. These improvements were not cosmetic. They came from focusing on the things that actually matter: raising graduation rates, increasing student survey participation, and focusing on affordability and indebtedness. The rankings validated real progress that improved the lives of students.

We did the same at the University of Kentucky. During my time there, we achieved our highest-ever U.S. News rankings in the history of the college. In 2020, the College of Education broke into the Top 30 among public institutions. In 2021 and 2022, UK’s online education programs reached the Top 15 nationally. These achievements were not about chasing prestige for its own sake. They were about ensuring that families could see that we were investing in the quality of the programs our faculty and staff had worked so hard to build.

Two Truths About Rankings

Here is where I land. Rankings are not destiny, but they are not irrelevant either. They are part of the language of higher education, and ignoring them altogether would be naïve. At their best, they can highlight progress in areas that are important like student engagement, access, and affordability. At their worst, they entrench privilege, celebrate exclusivity, and drive families toward bumper sticker logic. That is why I believe we need to hold two truths at once. First, rankings can validate institutional progress and help families navigate an overwhelming landscape. Second, rankings can distort priorities and reduce education to a prestige contest.

For parents, reclaiming agency means asking deeper questions than “Where does this school rank?” It means asking: Where will my child thrive? Who will mentor them? How will this institution prepare them not just for a first job but for a lifetime of learning? For students, reclaiming agency means remembering that your value is not determined by whether you get into a school that admits 5 percent of applicants. Your worth is not measured by whether your parents can put a bumper sticker on their car. For institutions, reclaiming agency means improving the measures that matter most for student success and being transparent about them, whether or not they move the needle in U.S. News.

Conclusion: Beyond the Scoreboard

Prestige may dominate headlines, but higher education is not a sport. Students are not statistics. Families are not fans. Universities are not competing for a championship trophy. Education is about transformation: developing minds, building character, and preparing citizens to lead meaningful lives.

Rankings can attract students, but they do not give them a good educational experience. College and universities have to do that class by class and experience by experience. That is where the real work happens, and that is where institutions prove their value. Rankings can tell part of the story, but can’t let them pervert education. And the sooner we remind ourselves, as parents, students, and leaders, that agency lies with us and not with ratings or bumper stickers, the better off our higher education system will be. Because your kid is not a ranking. And they are certainly not a bumper sticker.

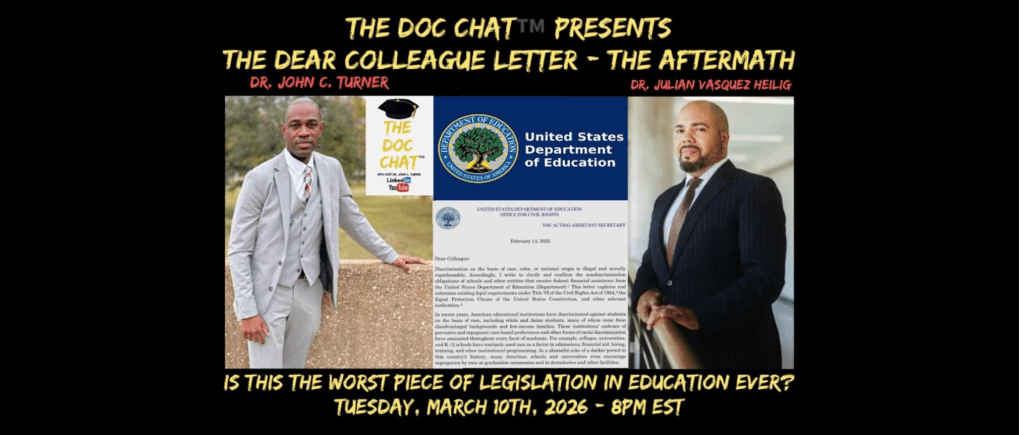

Julian Vasquez Heilig is a nationally recognized education leader, scholar, and advocate for equity whose career spans seven senior leadership roles in higher education, including dean and provost. Known for driving innovation and measurable results, he has led institutional transformations that strengthened academic programs, advanced diversity and inclusion, expanded community partnerships, and elevated national rankings. His leadership is grounded in the belief that true progress requires both bold vision and fearless action.

Leave a comment