The American republic has long claimed to be a guardian of the rule of law. A nation that, imperfectly but sincerely, places due process and judicial oversight at the center of its claim to legitimacy. Yet in recent months the United States government has moved very publicly in a different direction: administering lethal force in international waters against six small vessels (known so far) off the coast of Venezuela and justifying those strikes by labeling the people aboard “drug traffickers” or “narcoterrorists.” Those initial strikes, presented as surgical interventions in the war on narcotics, have become an ongoing dangerous precedent. When the executive branch substitutes public evidence and trials with executive fiat and CNN video releases, we should be alarmed, not because of the immediate tactical outcome but because of the long arc of what this normalization of extrajudicial execution makes possible.

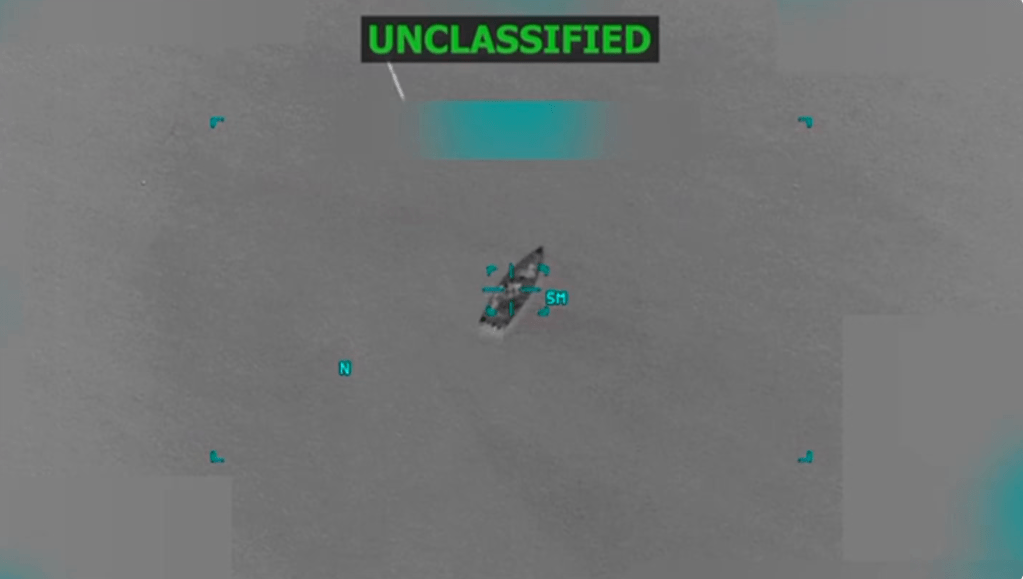

Let us be plain about what is happening. The administration has announced five maritime strikes in the southern Caribbean, the sixth and most recent was discovered by the media perhaps because there were survivors. Trump has claimed the vessels are tied to illicit narcotics networks and in at least one case asserting a link to a violent gang designated by the U.S. as a terrorist group. The White House and Pentagon have released footage of explosions and offered terse summaries of “intelligence” supporting the actions; families and foreign governments across Central and South America, meanwhile, have demanded answers about who was on those boats and what evidence existed of imminent threat. Human rights groups, United Nations experts, and a number of legal scholars have raised the alarm: killing people on the high seas in international waters without transparent evidence or an impartial judicial process is extrajudicial execution.

The Problems

There are three immediate and interlocking problems with this approach. First, the administration’s legal rationales have been opaque and ad hoc. Officials have invoked a diffuse “non-international armed conflict” with drug cartels, claimed self-defense, and pointed to executive authorities without releasing the legal memos or the specific intelligence that would allow independent verification. In the absence of such transparency, the public, and, critically, the Congress, cannot evaluate whether the strikes comport with U.S. criminal law, the law of armed conflict, or long-standing norms against assassination. In fact, we shouldn’t be evaluating at all. Judges and juries should be doing the evaluating in a court of law.

Second, the human cost of acting without public oversight is real and immediate. Families have lost relatives; foreign governments have protested; current and future independent investigators can only piece together fragments from social media videos and government political spin. Human Rights Watch and other organizations have characterized these maritime strikes as extrajudicial killings, underscoring that international human rights law does not permit governments to simply murder alleged drug traffickers. That is not an airy academic objection: it is a direct charge that the United States is abandoning principles that have historically constrained even the most powerful states.

Third, and here is where the language of “execution creep” matters — words and legal framings matter because they expand the circle of those who may be targeted. Today it is “drug traffickers” in the Caribbean; tomorrow it could be a political dissident labeled as a terrorist, a migrant boat “mistaken” for a drug smuggling operation, or a Chinese businessperson whose presence inconveniently collides with geopolitical objectives. Additionally, the Venezuelan winner of the Nobel Peace Prize could be a target of the CIA now, which makes her immediate phone call to Trump to tell him he actually deserved the award, suddenly makes sense. When a state normalizes killing abroad without presenting evidence or allowing judicial process, it lowers the institutional and moral barriers to killing with any cause in other contexts. This is not hypothetical: legal doctrines that once seemed restricted to battlefield contexts have a way of metastasizing into domestic and international political arenas when unchecked.

Execution Creep: A Sleight of Hand

We should be skeptical of the rhetorical sleight of hand that equates narcotics trafficking with an armed insurgency. Calling a criminal but fundamentally public health crisis “narcoterrorism” creates a conceptual loophole that allows traffickers to be treated as enemy combatants rather than criminal defendants. That linguistic trick is dangerous because it grants the executive branch a license to use military methods while bypassing the procedural safeguards that define the American justice system. It is precisely this framing that enables strikes in international waters without warrants, arrests, prosecutions, or trials. Whether one supports aggressive interdiction or not, the rule of law requires that lethal measures be narrowly defined, publicly justified, and subject to meaningful oversight.

Trump has now made it clear that CIA operations in Venezuela will not be hidden. He is openly escalating U.S. involvement in the region, suggesting that a president who presents himself as the “no war” candidate and even a Nobel Peace Prize hopeful is, in reality, preparing for another conflict. This is not new behavior for the U.S. government. For decades, extrajudicial actions carried out beyond public scrutiny, whether overseas or through covert domestic programs, have now been normalized and politically repackaged for domestic consumption on CNN and FoxNews. What was once secret has become spectacle, with acts of lethal force presented for cable news sound bites and partisan advantage.

Trump has said the U.S. is “looking at land now” and considering additional strikes on alleged drug cartels in Venezuela. The flurry of activity coincides with the abrupt retirement of Navy Admiral Alvin Holsey, commander of U.S. Southern Command (SOUTHCOM), which many interpret as a quiet protest against this escalation. Holsey’s jurisdiction includes the Caribbean Sea, where the U.S. has recently conducted these strikes at Trump’s direction. Yet in the same televised address, Trump told the “people of the United States” that his goal was “no war, yes peace.” The contradiction is glaring and deeply dangerous. Execution creep rarely begins with invasion; it begins with the quiet normalization of state violence that goes unquestioned until it becomes permanent.

The Drug Problem

Recognizing the threat is not the same as denying the scale of the drug problem. The flow of narcotics into the United States has real consequences. Communities have been devastated by addiction and overdose. Law enforcement and diplomacy have roles to play. But it is precisely because the stakes are high that we must insist on processes that respect legal norms. Letting the executive branch operate in the shadows, asserting “absolute and complete authority” without meaningful, independent review, is an escalating threat to American constitutionalism. The question is not only whether the strikes reduce drug supply; it is whether those tactics are consistent with the principles that separate a constitutional republic from a regime of arbitrary plenary power.

The irony is that the CIA has been entangled in this problem before. As dramatized in the Tom Cruise film American Made, U.S. intelligence agencies in the 1980s turned a blind eye to the narcotics trade, using drug profits to finance an illegal war in Nicaragua. That episode revealed how the language of “national security” can be used to justify covert corruption and violence that ultimately worsens the very crises it claims to fight. The lesson should have been clear: when agencies operate without oversight, the mission expands. What begins as “interdiction” morphs into a policy of impunity, justified by fear and executed in secrecy. To repeat that pattern today, under a president who promises “no war, yes peace” while authorizing lethal strikes and expanding CIA operations in Venezuela, is to ignore the institutional memory of our own abuses.

The Slide Toward Secrecy

When politicians normalize extrajudicial killing, they begin to look less like democracies and more like security apparats that erase opponents. Consider Russia’s record: a UK public inquiry concluded that the 2006 polonium poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko in London was “probably approved” at the highest levels of the Russian state; years later, the 2018 Novichok attack on Sergei Skripal in Salisbury was attributed by UK authorities and independent investigators to operatives of Russia’s GRU; watchdogs now track a wider pattern of transnational repression that includes multiple assassinations or attempts abroad; and the 2024 death of Alexei Navalny in prison drew swift condemnation from Western leaders who held the Kremlin responsible. These are the predictable end points when a government treats life-and-death decisions as matters for secret files rather than courts. Our charge, then, is not only to oppose any one policy but to reject the entire logic that puts unreviewable kill lists above the rule of law, because once that logic takes root, it rarely stops at the border.

Congressional Responsibility

So what should happen next? At a minimum, Congress must exercise its oversight responsibilities with urgency, and with skepticism. Lawmakers should remember how easily patriotic theater can be used to sell a war. It was not long ago that General Colin Powell was brought before Congress to present fabricated evidence about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, a performance that helped justify an invasion later revealed to be rooted as much in oil interests as in national security. We cannot afford to repeat that mistake under a new pretext.

Venezuela, too, happens to sit atop vast oil reserves. When a president who promises “no war, yes peace” begins authorizing lethal strikes and expanding CIA operations under the banner of drug interdiction, Congress should be asking who truly benefits. The American people deserve transparency, not another covert resource war disguised as counterterrorism or anti-narcotics enforcement.

Hearings should be held where classified evidence, appropriately protected, can be reviewed by the relevant committees; legal rationales should be laid before the public; and, if necessary, statutory constraints must be enacted to prevent the executive from conducting lethal operations in peacetime without clear legal authority and a narrowly tailored justification. International institutions also deserve a role: the United Nations and regional bodies should be permitted to investigate and publish findings. Human rights organizations must be free to document, litigate, and hold actors accountable, because democracy cannot survive on faith alone.

Conclusion

Finally, citizens must insist on something more fundamental than tactical resistance to a particular policy: we must insist on our democratic inheritance. Democracy is not just a system for selecting leaders; it is a set of institutional checks and cultural habits that protect the powerless from the powerful. When the state claims the right to kill on the say-so of an agency or an anonymous “intelligence” report, it undermines that inheritance. We should be able to fight crime without losing our constitutional soul.

The strikes off the coast of Venezuela are, in their immediate facts, acts of lethal force justified by national security rhetoric. But their significance runs deeper: they are an experiment in how far an executive will go before being stopped. If we tolerate these extrajudicial strikes because they feel expedient or because political theater demands a show of toughness toward theoretical bad guys, we tacitly license a broader erosion of due process. That is the lesson of execution creep, and it is a lesson we cannot afford to learn at the cost of our legal and moral standing in the world.

Julian Vasquez Heilig is an award-winning civil rights leader, scholar, and public intellectual whose academic leadership career has spanned two decades in higher education. He has served as provost and vice president for academic affairs at Western Michigan University, dean of the College of Education at the University of Kentucky, and held faculty and leadership roles at the University of Texas at Austin, and California State University Sacramento. As the first provost of color at WMU, he led major institutional transformation initiatives while championing equity, shared governance, and inclusive excellence. A national voice on education policy, leadership, and social justice, he has testified before state legislatures, advised political campaigns, and keynoted across the world. Vasquez Heilig writes the Without Fear or Favor newsletter on LinkedIn which has been read by 1.5 million people in 2025. He is the founding editor of the acclaimed blog Cloaking Inequity.

Leave a comment