Yesterday I was on campus at the University of Michigan for a VIP event and announcement that gathered faculty, students, and alumni in a celebration. However, it’s not public yet, so I can’t announce it here.

The air in Ann Arbor carried that crispness that only early autumn seems to hold, a mix of clarity and calm that makes even familiar places feel new. Before the ceremony, the speeches, and the free food that followed, I sat down at a table across from Matthew Solomon, a professor of film at the university. Hoping to begin an easy conversation, I asked what I thought was a simple question: “What’s your favorite film?” The moment I said it, I realized he had probably been asked that question thousands of times before, just as people constantly ask me what I teach. Oooops.

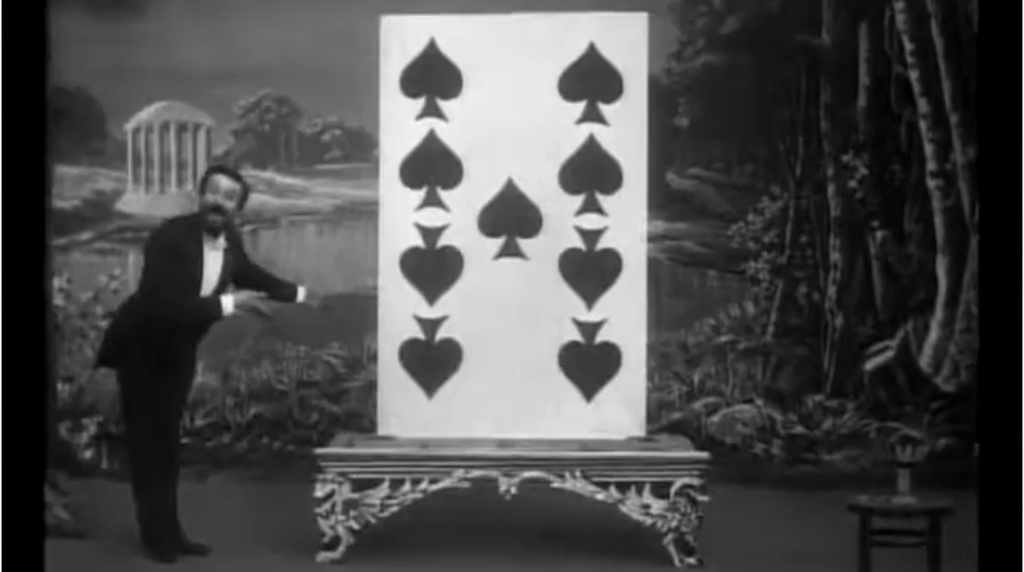

He smiled patiently and answered without hesitation. His favorite film, he said, was The Living Playing Cards by Georges Méliès. The choice surprised me. I had expected a more conventional answer, maybe a golden era Hollywood classic or something from the modern drama canon, not a short silent film made more than a century ago. Then he insisted that I take three minutes right there at the table to watch it so we could discuss it properly. I was game. As the buzz of conversation filled the room, I opened my phone, found the short, and pressed play. Here it is.

Three Minutes of Magic

The film unfolded in silence. In a small theatrical set, Méliès appeared surrounded by giant playing cards. Through clever camera and editing tricks, the cards spun, transformed, and turned into people who danced, bowed, and disappeared again. The illusions are simple by modern standards, but they carry an unmistakable sense of play and wonder. It was as if the filmmaker had discovered a new technological language and was learning to speak it one image at a time. When the film ended, I understood why Solomon loved it. It was not about plot or characters. It was about the joy of invention. Méliès had turned the camera into a tool of imagination rather than imitation. Solomon told me I could watch the film a thousand times and learning something new each time.

I sat for a moment thinking about the significance of that three-minute experience. Méliès began as a stage magician, but his curiosity led him to experiment with the camera, which was a new technology in his time. He used it not to document reality but to reshape it. His art was not about spectacle but about discovery. He revealed that every new tool carries within it the potential to extend human creativity. Watching his film, I could feel that early energy of experimentation that still drives film makers, artists, and innovators a century later.

The Problem of Learning Without Learning

That brief encounter with Méliès’s world made me think about my own work in education. We are living in a moment when technology can produce near-perfect results with very little human effort. I recently heard stories about accounting students finishing college without truly knowing how to perform accounting tasks because they had farmed their work out to AI systems. It struck me as a quiet tragedy. These students graduated from college with the ability to get answers but not the understanding of how those answers were formed. They totally missed the process of struggle that deepens comprehension and would make them competent accountants. The technology, which should have been a tool for insight, had become an obstacle to genuine learning.

The ease of automation tempts students to substitute efficiency for engagement. I know this intimately from my teens. But real learning requires time, patience, and the willingness to make mistakes. It depends on the same kind of persistence that Méliès brought to his experiments. He worked within limitations, using film stock that was fragile and unpredictable, yet those constraints became the source of his creativity. In the same way, the limits of human effort and the imperfections of manual learning give rise to understanding. When students let AI handle the work, they lose the discipline that leads to mastery.

Design Thinking and the Human Element

In my own classroom, I have been working to counter this AI-induced problem by focusing on design thinking and active learning. Design thinking invites students to approach challenges with empathy, curiosity, and experimentation. It values iteration over perfection and encourages collaboration over isolation. When students prototype, test, and revise their ideas, they rediscover the satisfaction of discovery. The goal is not to eliminate AI from the classroom but to place it in the background, as one tool among many. What matters is not how sophisticated the software becomes, but how thoughtfully it is used.

When students learn through design-based activities, they cannot simply hand their thinking to an AI or machine. They must engage their senses, work through problems, and communicate with one another. The classroom becomes a workshop for curiosity rather than a production line for output. It reminds students that creativity is not an act of consumption but an act of construction. The more they experiment, the more they see that knowledge is something we make, not something we buy.

Innovation and the Unknown

Watching The Living Playing Cards reminded me that every technological breakthrough begins with uncertainty. The first time Méliès saw a camera, he did not know exactly what to do with it. He experimented until he discovered that stopping and restarting the film could create the illusion of transformation. What began as a experiment became a method. The same process is now unfolding with artificial intelligence. AI is learning to create, to synthesize, and to simulate, yet we do not fully understand how it learns. In the post AI Code Red: The Mystery and Power of Emergent Behavior I reflected on Bill Gates’s admission that we do not truly know how AI teaches itself, it’s emergent behavior. That mystery still lingers. We have unleashed something that mimics intelligence but operates in ways that exceed our comprehension.

This uncertainty is both revolutionary and dangerous. Like Méliès’s experiments, AI’s capabilities often reveal themselves by accident. The challenge is to manage that unpredictability with purpose. Innovation must always be balanced with introspection. If we fail to understand what our tools are doing, we risk losing sight of why we use them. Méliès’s art succeeded because he paired experimentation with intention. Each trick was designed to surprise, to delight, and to expand what audiences believed was possible. AI will require the same kind of human guidance. Without it, creativity could drift into automation without accuracy or meaning.

Technology and the Measure of Progress

The event yesterday celebrated progress, and the word itself seemed to echo through everything I saw and heard. Progress, however, is never neutral. It reflects the values of the people who define it. The printing press, the camera, the computer, and now AI have each transformed the way humans share knowledge. Yet every leap forward comes with the risk of losing the personal connection that makes knowledge meaningful. The question is not whether AI will change the world. It already has. The real question is whether we will use it to deepen our humanity or to distance ourselves from it.

Walking across the campus to my car after the event wound down, I thought again about Méliès and his short film. The sunlight filtered through the branches of the turning trees, painting the paths in shades of amber and gold. It felt like a scene that could have come from one of his sets, fleeting but vivid. Creativity, I realized, is always seasonal. It requires patience, reflection, and a willingness to let old methods fall away so new ones can take root. Autumn, with its quiet transformation, is the perfect metaphor for the moment we are living in now. AI is part of that transformation, and like the season itself, it asks us to embrace change while remembering what must endure.

The Lesson of Groundhog Day

As I drove away from campus in bumper to bumper rush hour traffic, I thought about my favorite film, Groundhog Day. It tells the story of a man trapped in time who learns that repetition can lead to renewal. Each morning he wakes to the same world, but each day he has the chance to live it differently. That story has always spoken to me as a metaphor for learning and creativity. Innovation, like life, often feels repetitive. We encounter the same challenges again and again, but each time we bring a little more understanding to them. Progress is not about escaping repetition. It is about transforming it into wisdom.

The connection between Groundhog Day and The Living Playing Cards feels clearer now. Méliès captured the excitement of creation, the first spark of imagination that technology can ignite. Groundhog Day captures what follows, the long process of reflection that turns invention into insight. Both are about time, patience, and the art of seeing familiar things with new eyes. AI belongs in that same continuum. It will not replace our capacity to create or to learn. It will only magnify whatever mindset we bring to it.

If we approach it carelessly, we will repeat the same mistakes in new forms. But if we approach it thoughtfully, with the curiosity of Méliès and the perseverance of Phil Connors, we can turn this moment into one of genuine renewal. The challenge of our time is to balance speed with reflection, capability with conscience, and repetition with revelation. Each day offers another chance to learn, to refine, and to see differently. That, perhaps, is the truest form of progress.

By the time I reached the edge of Ann Arbor, the last light was slipping through the trees, and I felt grateful for the unexpected conversation that had led me to an old film and a new perspective. Méliès’s magic trick and Groundhog Day’s cycle of renewal had merged into a single idea: technology is only as creative as the intention behind it. The future will belong to those who use it not to escape thought but to think and experience more deeply.

Please share

Julian Vasquez Heilig is a nationally recognized education policy scholar, public intellectual, and advocate for equity in learning and leadership. His writing explores the intersections of innovation, imagination, and justice in education and public life. Beyond policy, he enjoys writing about culture, film, and the stories that reveal how creativity connects human experience across time and technology.

Leave a comment