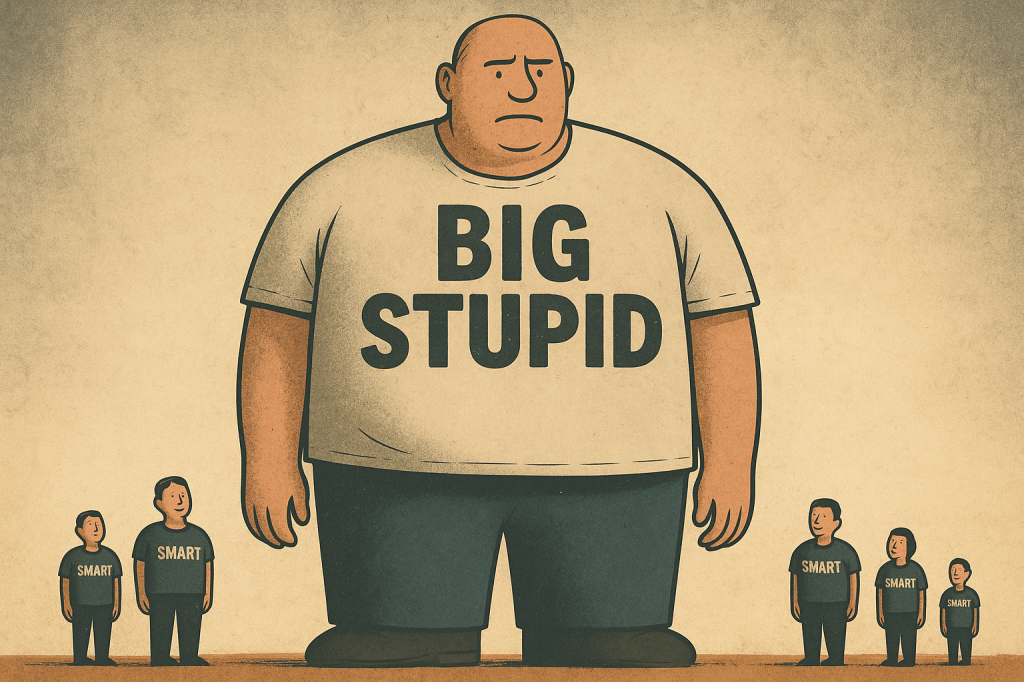

We are living through a moment that feels heavier than a cultural trend. Esquire recently described this period with unsettling accuracy by calling it an age of “Big Stupid.” The description is blunt, yet it captures a mood that is no longer hidden beneath the surface of public life. We are not simply indifferent to intellect. We are actively suspicious of it. This suspicion shapes our politics, our conversations, and our decisions about how schools should function. What once appeared as irritation toward complexity has transformed into hostility toward the very act of thinking.

The Big Stupid moment is visible across sectors and institutions. Reflection is framed as hesitation. Nuance is framed as weakness. Expertise is framed as manipulation. Evidence is framed as inconvenience. The distrust operates as a cultural script that encourages people to believe that ideas requiring thought are a kind of danger. The louder the accusation, the more likely it is to be repeated. The more complex the issue, the quicker it is dismissed. The cumulative effect is a society that treats thoughtful engagement as an obstacle to be removed.

America has always carried threads of anti-intellectualism, yet the current atmosphere has a different texture. It feels organized. It feels amplified. It feels purposeful. The result is a collective environment in which attention gravitates toward simplicity, outrage, and spectacle. The experience is disorienting because the pressure is constant. People begin to internalize the belief that careful thought is unnecessary or even suspicious. When thinking becomes suspect, the consequences for public life are profound.

How We Arrived at This Moment

The Esquire article points toward a troubling development. The rejection of intellect no longer reflects only cultural mood. Big Stupid has become a profitable model. Media platforms grow quickly by flattening every issue into simple categories that demand no curiosity. These platforms reward quick reactions instead of genuine understanding. They profit from conflict because conflict requires no explanation. They encourage people to participate in public conversation without asking for context or accuracy.

This incentive structure shapes how many people engage with the world. It pushes complexity aside because complexity takes time. It sidelines reflection because reflection requires patience. It discourages contradiction because contradiction forces people to consider they may be wrong. The entire system thrives on immediacy because immediacy keeps people scrolling. The outcome is an environment where thinking is unnecessary for participation.

Education feels this pressure intensely. Teachers encounter demands that conflict with the purpose of learning. They are asked to produce higher test scores without nurturing curiosity. They are encouraged to create classrooms that value narrow efficiency instead of open inquiry. They face scrutiny for asking students to consider ideas that may complicate political narratives. The public claim is that educators promote ideology. The quieter truth is that many educators are punished for promoting thinking.

Students witness all of this. They see adults fear books that expand understanding. They see policymakers warn against teaching history that reveals contradiction. They see parents pressured to oppose history lessons they have not personally read or discussed. Young people absorb the message that ideas themselves are dangerous. When the culture surrounding education teaches students that curiosity is a risk, the long-term consequences of Big Stupid for society are difficult to ignore.

The Politics of Rejecting Thought

Political incentives today reward people who offer simple answers to complex issues. Candidates gain visibility by expressing certainty even when the situation requires humility. They build entire followings by presenting ignorance as authenticity. The less they understand, the more their supporters view them as relatable. This creates a political environment where the performance of confidence matters more than the practice of thinking.

This environment shapes the public’s expectations. People begin to seek leaders who reassure them that problems have easy solutions. They gravitate toward those who promise resolution without explaining the trade-offs. They reward individuals who avoid contradiction because contradiction reminds us that the world requires attention. As this pattern grows, the idea of intellectual humility becomes less visible in public life.

Policy making becomes distorted by this Big Stupid culture. Decision makers lean toward whatever plays well in front of a camera. They rely on instinct rather than evidence. They evaluate ideas based on how they sound instead of whether they work. They focus on generating outrage because outrage is faster than governing. The issue is not the presence of disagreement. The issue is the absence of thought. When political culture discourages thought, the results accumulate quietly until they shape entire systems.

Schools on the Front Line

Schools remain one of the few public institutions designed to cultivate thought. They are meant to support curiosity, analysis, interpretation, and inquiry. This purpose places them at the center of conflict whenever anti-intellectual attitudes rise. When a society begins to distrust thinking, it begins to distrust the places where thinking is taught.

Book bans spread across communities with nearly identical patterns. The pressure to restrict reading lists grows louder than the discussions about why the books were chosen. Curriculum restrictions are imposed by people who view complexity as harmful rather than essential. Teachers face scrutiny for assigning material that requires students to analyze or question. The concern is framed as moral protection, even though the deeper worry often revolves around uncertainty and fear.

Students are watching the Big Stupid shifts unfold. They learn quickly that certain topics are controversial simply because adults label them so. They notice how some communities praise knowledge while others fear it. They see how educators struggle to balance honesty with caution. These observations shape how young people interpret the purpose of education. When they see adults limit thinking out of fear, they begin to question whether thinking is safe.

The Consequences of This Cultural Moment

The greatest danger of anti-intellect Big Stupid is the slow erosion of our collective ability to recognize poor decisions. Societies make mistakes. That is part of human experience. The true risk emerges when societies lose the habits that help them identify mistakes and learn from them. Thoughtful self-correction requires evidence, analysis, conversation, and humility. When these capacities are dismissed, communities drift into habits of reaction rather than habits of understanding.

The erosion happens gradually. People stop reading books and media deeply because reading disrupts quick assumptions. They rely on slogans and memes and social media reels because they feel comforting. They avoid challenging ideas because challenging ideas disrupt certainty. They lose the confidence to engage with complexity because complexity feels like confusion. When these habits become routine, public conversation loses texture. Everything becomes easier to flatten. Everything becomes easier to manipulate.

Once a society abandons its intellectual tools, it also abandons the ability to govern itself effectively. Public life requires thoughtful participation. Democracy requires informed judgment. Communities require people who are willing to ask questions and stay with difficult ideas long enough to understand them. Without the capacity to think together, we are left with noise that cannot produce meaningful solutions.

Reclaiming Thinking as a Public Value

Rebuilding the culture of thought requires more than intelligence. It requires a sustained commitment to curiosity, dialogue, and inquiry. People need opportunities to discuss ideas without fear of humiliation. Communities need spaces where disagreement does not end conversation. Schools need support to teach the subjects that strengthen reasoning. Leaders need courage to admit what they do not know.

We play an essential role in this work as we shape the culture of conversation at dinner tables, in workplaces, in community groups, and in moments of casual debate. We influence whether children see ideas as opportunities or threats. We demonstrate whether curiosity is something to celebrate or something to avoid. We create the habits that determine whether thinking feels safe.

This work begins with a simple practice. It begins when someone chooses to rise, steady themselves, and ask a question that demands more courage than convenience. A person who asks a difficult or better question signals that thinking is still possible in a Big Stupid world that often treats thought as risk. That decision becomes an invitation for others to pause, reflect, and reconsider what they assumed they already understood. It opens the door to dialogue that cannot be reduced to noise. It creates space for clarity that cannot be packaged into slogans. It offers understanding that grows through patience rather than performance.

A single question carries more power than it appears to hold. It can interrupt the patterns that sustain “Big Stupid.” It can unsettle the habits that make people fear complexity. It can remind communities that inquiry is a strength. A question asked in good faith reconnects people to the value of exploring ideas without predetermined conclusions. It becomes a moment when the culture hesitates long enough to imagine something different than Big Stupid.

Julian Vasquez Heilig is a nationally recognized policy scholar, public intellectual, and civil rights advocate. A trusted voice in public policy, he has testified for state legislatures, the U.S. Congress, the United Nations, and the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, while also advising presidential and gubernatorial campaigns. His work has been cited by major outlets including The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Los Angeles Times, and he has appeared on networks from MSNBC and PBS to NPR and DemocracyNow!. He is a recipient of more than 30 honors, including the 2025 NAACP Keeper of the Flame Award, Vasquez Heilig brings both scholarly rigor and grassroots commitment to the fight for equity and justice.

Leave a reply to Dr. Julian Vasquez Heilig Cancel reply