At some point in life, many people find themselves in a situation where something important is unraveling and the person with the most authority to address it helped cause or caused the problem. This may happen at work, on a team, in a school, in a community organization, or even in a club that promised to be fun and somehow became political. Sometimes the damage is easy to see, such as declining results, strained relationships, no confidence votes, or public embarrassments. Other times the damage shows up quietly, through fatigue, hesitation, or the steady loss of people who once cared deeply. What makes this moment especially difficult is not just the mess itself, but the growing realization that you disagree with how the person in charge wants to clean it up. That realization can sit with you for a long time, maybe months, before you say it out loud.

This situation is not reserved for executives or people with formal authority. Everyday leaders encounter it constantly because they live closest to the consequences of decisions they did not make. You may not control the strategy, the budget, or the final call, but you still feel responsible for what is happening around you. You see how decisions land on real people. You carry the emotional weight of outcomes even when you lack positional power. In these moments, leadership stops being about titles and becomes about judgment. The question quietly shifts from “What should they do?” to “How will I act inside this reality?”

One of the hardest parts of this experience is accepting the limits of your control. You cannot undo past decisions, even when you can clearly see their effects. You cannot force someone above you to see what they are unwilling or unable to acknowledge. You cannot fix a system alone that was built over time by many people. What you can do is decide how you will show up without losing your integrity. That decision matters more than most people realize, especially when circumstances are less than ideal.

Understanding the Nature of the Mess You Are Facing

Before responding, it is essential to understand what kind of mess you are actually dealing with. For example, is it a multi-millions dollar mess? Not every problem signals the same level of risk or responsibility. Some people make mistakes in good faith under pressure, stress, or incomplete information. Others avoid accountability, dismiss feedback, or repeat patterns that have already caused harm because they are managers not everyday leaders with vision. Without clarity about which situation you are in, frustration can turn into actions that worsen the problem rather than improve it. Careful observation is a form of leadership in itself.

It also helps to understand what kind of disagreement you are experiencing. Sometimes the conflict is about priorities or timing rather than values. Other times it is about fairness, honesty, or how people are treated when things go wrong. In some cases, the issue is simply capacity, meaning the plan exceeds what the people involved can realistically deliver. Each of these situations calls for a different response. Treating them all the same often leads to misplaced frustration or ineffective resistance.

Everyday leaders benefit from slowing down long enough to name what feels off. This does not require certainty, but it does require honesty with yourself. You may discover that what bothers you most is not the decision itself, but the way it was communicated. Or you may realize the strategy could work in theory but fails to account for human limits. You may also realize that the issue touches values you are not willing to compromise. Or they simply screwed up royally. Understanding these contours helps you respond deliberately rather than reactively.

Speaking Up Without Becoming the Problem

Disagreement is inevitable wherever people are trying to do meaningful work together. The way disagreement is expressed shapes whether it leads to learning or damage. Many people default to venting quietly, signaling frustration through tone, or sharing concerns only with those who already agree. While understandable, these habits rarely create change. Over time, they often reduce trust and weaken influence. Everyday leaders learn to handle disagreement with discipline and surely without yelling and intimidation.

When you choose to speak up, grounding your concerns in patterns and consequences matters. Focusing on how decisions affect people and outcomes keeps the conversation anchored in community purpose. Framing concerns around risk and sustainability tends to invite listening more than framing them around blame. Timing also matters, as does choosing spaces where honest conversation is possible. Speaking respectfully does not mean speaking timidly, but it does mean speaking with courage and care.

There is also an important moment when you realize you have said what needs to be said. Repeating the same concern over and over can shift how others perceive you. What began as principled input can start to feel like resistance for its own sake. Knowing when to pause preserves credibility and leaves space for future influence. Everyday leadership often involves restraint as much as voice.

Protecting People and Purpose Even When You Disagree

One of the most difficult leadership distinctions is separating loyalty to a person from responsibility to a purpose. Especially when you want to be loyal to the person that hired you. When decisions above you feel misguided, it can be tempting to disengage emotionally or withdraw effort also known as “quiet quitting.” That response is understandable, but it often deepens harm for those who have the least power in your community. Everyday leaders protect people even when they feel disappointed by leadership. That protection shows up in small, consistent actions.

Protecting what matters does not require pretending everything is fine. It requires maintaining standards in your own work and interactions. It involves being mindful of how your words affect morale and trust. Cynicism spreads quickly, especially during uncertain times. Leaders at every level influence culture through what they normalize and what they challenge.

There is also value in remembering how quickly narratives harden. When decline is constantly described as inevitable or comparable to the market, teams and people actually stop trying to improve things. 1,000 excuses arise or other priorities/sidetracks are taken on rather than the actual thing that is the problem. Everyday leaders resist that slide by focusing on what can still be done well. They create pockets of care and competence even when the larger system feels unstable. This quiet stewardship often matters more than public critique.

Working With Some People Who Are Solid But Not Particularly Motivated

These situations become more complicated when the people around do not desire to be especially strong performers. They may be solid, reliable, and well intentioned, but not particularly adaptable or imaginative. In calm periods, this may not matter much. In moments that require repair or reinvention, it becomes a constraint. Expecting average contributors to suddenly exceed their range often leads to frustration on all sides.

Everyday leaders respond to this reality with clarity rather than resentment. Clear routines and priorities often matter more than inspirational speeches. People perform better when they know exactly what is expected and what matters most. It is also important to recognize where growth is possible and where it is not. Some people can stretch with support and feedback. Others are already operating at their ceiling because of disinterest. Naming this honestly helps everyone involved. Avoiding the issue in the name of calm often creates more harm than addressing it directly.

Resisting the Urge to Carry Everything Yourself

When leadership above you falters and some colleagues around you are disinterested, the temptation to carry everything yourself is strong. You step in to smooth rough edges, absorb extra work, and prevent visible failure. For a while, this may keep things afloat. Over time, it almost always leads to exhaustion and resentment. It also hides the true state of the system.

Carrying everything sends misleading signals to everyone involved. Those above you may believe that their plans are working because consequences are being quietly absorbed and honest information doesn’t reach them. The organization learns the wrong lesson about what is sustainable. What feels like commitment slowly becomes self erasure. Everyday leadership requires boundaries. Knowing what you can reasonably carry is an act of self respect. Expressing and allowing strain to surface is sometimes the only way executive leaders in systems learn about reality. Durability comes from pacing, not sacrifice without limit. Leadership that is sustainable understands this difference.

Knowing When Staying Is Growth and When Leaving Is Integrity

There are moments when disagreement moves beyond discomfort and becomes a question of integrity. When you are asked to defend or carry out professional actions you believe are harmful, dishonest, or unjust, remaining in place can begin to erode your sense of self. Resisting in such moments is not a failure of commitment. It is often an act of alignment with your values. Once you concede to professional actions you know are harmful or dishonest, it rarely ends there, as each concession makes the next one easier.

Choosing to leave should be deliberate rather than reactive. It involves finishing responsibilities with care and respecting the relationships you have built. It also involves resisting the urge to make your departure a statement. Quiet exits often preserve more dignity and future credibility than dramatic ones. How you leave becomes part of your leadership story and build towards your next opportunity.

As I discussed in the post, The Seduction of Hope: Why Your Job Feels Impossible to Leave, it is also worth examining why you stay. Fear, loyalty, and habit can keep people in situations long after growth has ended. Sometimes staying teaches patience and restraint. Other times staying teaches avoidance. Everyday leaders learn to tell the difference. Integrity often depends on that clarity.

Everyday Leadership in Imperfect Systems

Most leadership does not happen in ideal conditions. It happens in classrooms, offices, teams, and communities where power is uneven, decisions are inherited, and outcomes are uncertain. Everyday leaders are often asked to work in the aftermath of choices they did not make, repairing damage without the authority to redesign the system that produced it. They do not wait for permission to act with care. Instead, they focus on how they speak, how they listen, and how they protect people when things feel unstable. These choices accumulate over time, shaping trust even when control is limited.

Everyday leadership is seldom loud or celebrated. It shows up in small, repeated professional choices made while cleaning up messes that belong to someone else. It means choosing steadiness when reactivity would be easier and choosing community well-being when convenience would be rewarded. It often involves absorbing strain, restoring clarity, and preventing further harm while knowing that credit may never come. These moments rarely earn recognition, yet they quietly shape whether others feel supported enough to stay engaged and hopeful.

Everyday leaders are not defined by whether they avoid messes or discomfort. They are defined by how they move through difficulty without surrendering their values or their humanity, even when they are fixing problems they did not create. That work requires patience, humility, and a kind of courage that does not expect applause. It is the discipline of staying grounded when others turn away. Over time, this is how everyday influence deepens into community strength and sustainable leadership, not by having the final word, but by holding the line on care, clarity, and responsibility.

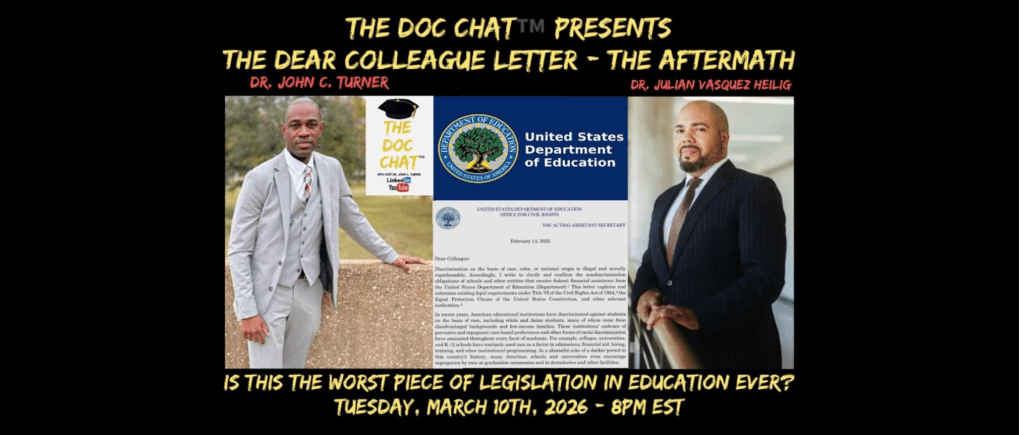

Julian Vasquez Heilig is a nationally recognized policy scholar, public intellectual, and civil rights advocate. A trusted voice in public policy, he has testified for state legislatures, the U.S. Congress, the United Nations, and the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, while also advising presidential and gubernatorial campaigns. His work has been cited by major outlets including The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Los Angeles Times, and he has appeared on networks from MSNBC and PBS to NPR and DemocracyNow!. He is a recipient of more than 30 honors, including the 2025 NAACP Keeper of the Flame Award, Vasquez Heilig brings both scholarly rigor and grassroots commitment to the fight for equity and justice.

Leave a comment