For almost a year, schools, colleges, and universities across the country lived under an extraordinary cloud of uncertainty. The Trump administration did not merely criticize diversity, equity, and inclusion. It decided to use federal power to threaten institutions with the loss of funding if they continued any practices the administration unilaterally labeled as “DEI.” Through a Dear Colleague letter and subsequent certification demands, the Department of Education attempted to redefine civil rights law by fiat. To many in higher education, that effort was not subtle, and it was not cautious— it was designed to chill speech, reshape institutional behavior, and intimidate educators into silence.

I appeared on DemocracyNow! when the Dear Colleague letter was first released to discuss.

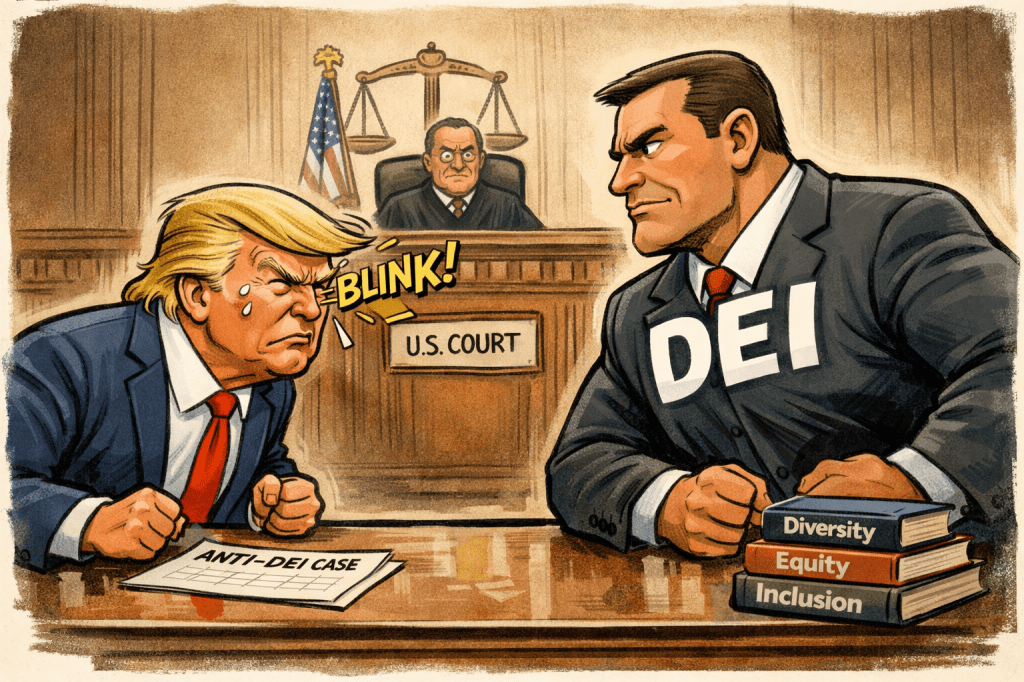

Last week, that campaign effectively collapsed for now. The administration dropped its appeal of a federal court ruling that blocked the anti-DEI guidance. In legal terms, the move leaves the district court’s decision intact. In political terms, it signals something much larger. After months of threats, investigations, and public pronouncements, the administration blinked first. The federal government stepped back from an effort that a judge had already described as unconstitutional, procedurally defective, and corrosive to free speech.

This matters far beyond the courtroom. The original guidance did not simply target admissions decisions. It cast a wide net over all aspects of student, academic, and campus life. Faculty worried about what they could teach. Administrators questioned whether mentoring programs, campus visits, scholarships, or outreach efforts could suddenly be framed as illegal. K–12 educators were asked to certify compliance with a vague and ideologically driven interpretation of Title VI. The goal was not clarity. The goal was fear.

The federal court saw through it. Judge Stephanie Gallagher concluded that the Department’s actions stifled speech and caused educators to reasonably fear punishment for lawful and even beneficial practices. The administration’s decision to abandon its appeal is an implicit acknowledgment that defending this approach was becoming untenable. When the government stops fighting for a policy it once touted as essential, it is rarely because of confidence. It is because the legal, political, and moral costs have become problematic.

Yet it would be a mistake to read this as a full retreat from the broader anti-DEI project. The Department has already insisted that it retains authority to pursue investigations under Title VI, with or without the withdrawn guidance. The rhetoric has softened, but the posture has not disappeared. What has changed is the terrain. The most aggressive effort to enforce an expansive, punitive interpretation of anti-DEI ideology through a single sweeping federal directive has failed.

This moment reveals something important about how power works in higher education. DEI efforts did not survive because they were fashionable or symbolic. They survived because educators, unions, students, and institutions pushed back using evidence, law, and collective action. The American Federation of Teachers challenged the guidance not with slogans, but with constitutional arguments and administrative law. Faculty continued to teach, mentor, and research despite the chilling effect. Universities documented the real educational value of access-oriented practices. In the end, the administration could not sustain its claims in court.

The lesson here is not that the threat is over. It is that DEI, when grounded in research and embedded in institutional practice, is far more important for student and faculty success than its critics assume. The administration’s failure underscores a deeper truth. Diversity, equity, and inclusion are not abstract ideals floating above the academy. They are operational practices tied to recruitment, retention, mentorship, curriculum, and student success. When those practices are thoughtfully designed and theoretically grounded, they are not easy to dismantle with rhetoric alone.

That is precisely why the pause on DEI attacks aligns so closely with our new peer-reviewed research. In our article, Creating Access and Opportunity: How Mid-Level Academic Leaders and Their Campus Partners Implement and Support Innovative Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Recruitment, published in the journal Professing Education, we examined how DEI actually functions on the ground at research universities. Rather than treating DEI as a set of slogans or offices, we analyzed how Associate, Assistant, and Vice Deans translate equity commitments into durable institutional practices.

Drawing on case studies from the University of Michigan, Western Michigan University, and the University of Kentucky, our research shows that access- and opportunity-driven recruitment succeeds when it is built around social and cultural capital. Mid-level academic leaders play a crucial role in this process. For example, they design campus visits that demystify higher education for students from under-resourced schools. They build mentorship networks that connect students to peers, faculty, and institutional decision-makers. They partner with K–12 schools and communities to create pipelines that extend far beyond a single admissions cycle.

What makes these efforts resilient is that they are not symbolic. They are embedded. At Michigan, outreach and mentorship programs have been scaled across colleges and aligned with undergraduate education structures. At Western Michigan, culturally affirming recruitment experiences such as Unity Weekend integrated identity, belonging, and academic exposure in ways that build confidence and institutional fluency. At Kentucky, digital storytelling and social media engagement expanded access to information, networks, and institutional knowledge for students who might otherwise be excluded from informal pathways to college readiness.

Our analysis is grounded in Bourdieu’s concepts of social and cultural capital, not as abstract theory, but as practical tools for leadership. Bridging social capital connects students to new networks. Linking social capital connects them to institutional power and resources. Cultural capital equips them with the knowledge to navigate academic environments that were not necessarily designed with them in mind. When recruitment strategies intentionally build these forms of capital, they do more than increase enrollment numbers. They transform access into opportunity.

This is why the administration’s anti-DEI effort ultimately faltered. It attempted to collapse complex, research-based practices into caricatures of “preferential treatment.” It ignored decades of scholarship demonstrating that inequity is produced structurally, not accidentally. It treated DEI as a political and ideological intrusion rather than as an evidence-based response to persistent underrepresentation. Courts are often cautious institutions, and they recognized that the government’s approach was legally and procedurally baseless.

The deeper irony is that the administration’s retreat comes at a time when the need for access-oriented leadership is more urgent than ever. Research-intensive universities continue to struggle with the underrepresentation of students from rural, urban, and under-resourced high schools. Traditional recruitment strategies still privilege students with inherited cultural capital and insider knowledge. Without intentional intervention, higher education reproduces inequality while claiming neutrality.

Our new study argues that mid-level academic leaders are essential to disrupting that cycle. Positioned between faculty, senior administration, and students, they are uniquely situated to translate values into practice. They are also the pipeline to future deans, provosts, and presidents. When they understand DEI as mission-critical infrastructure rather than optional programming, equity becomes harder to roll back in moments of political pressure.

The administration blinking first does not mark the end of resistance to DEI. It marks a reminder. When equity work is superficial, it is easy to attack. When it is embedded, evidence-based, and aligned with student, staff, and faculty success, it is far more difficult to dismantle. The courts did not defend DEI because of ideology. They defended constitutional process and free speech. Educators defended DEI because it works.

In that sense, this moment is not just a legal footnote. It is a confirmation of what many of us already knew. Access and opportunity are not luxuries in higher education. They are central to its public purpose. Attempts to govern by rule-making based intimidation usually collapses under its own weight. Institutions that invest in theory-driven, community-engaged, and human-centered equity practices are better positioned not only to survive political headwinds, but to continue expanding opportunity for all students, staff, and faculty when those headwinds shift.

Trump blinked first on DEI. The work for all communities, however, continues.

Julian Vasquez Heilig is a nationally recognized policy scholar, public intellectual, and civil rights advocate. A trusted voice in public policy, he has testified for state legislatures, the U.S. Congress, the United Nations, and the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, while also advising presidential and gubernatorial campaigns. His work has been cited by major outlets including The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Los Angeles Times, and he has appeared on networks from MSNBC and PBS to NPR and DemocracyNow!. He is a recipient of more than 30 honors, including the 2025 NAACP Keeper of the Flame Award, Vasquez Heilig brings both scholarly rigor and grassroots commitment to the fight for equity and justice.

Leave a comment