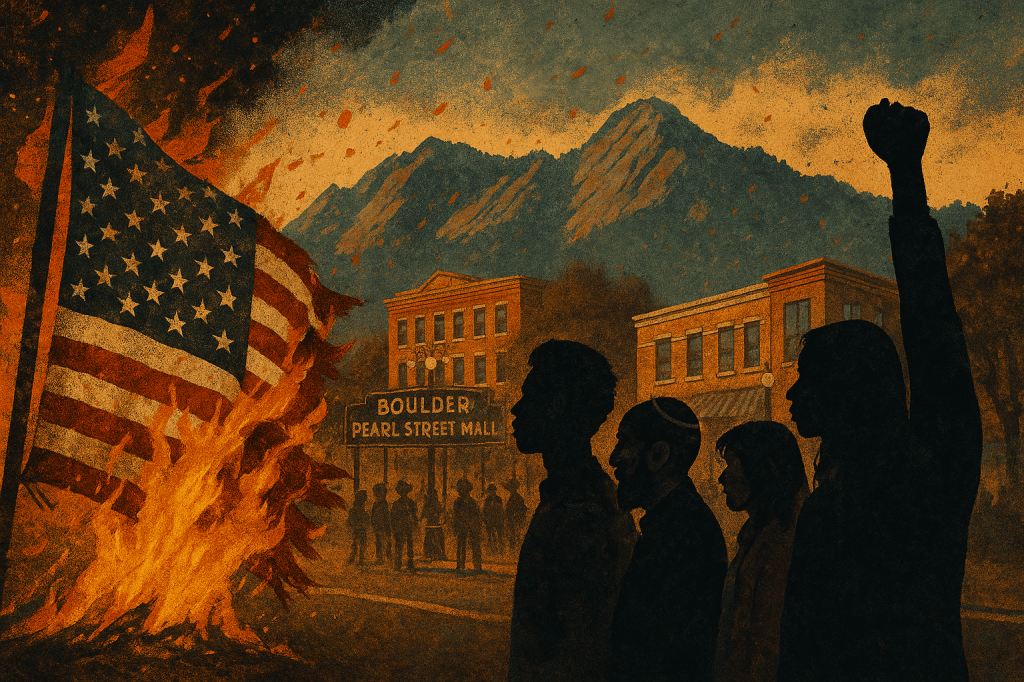

Let’s be honest about something uncomfortable. Racism is still on fire in America.

On June 1, 2025, Boulder, Colorado became the latest site of a horrific act of violence in America. At 1:26 p.m., a group of peaceful marchers—many elderly—were walking through the Pearl Street Mall in their regular weekly gathering. In broad daylight, a man identified as Mohamed Sabry Soliman allegedly attacked them with a homemade flamethrower and an incendiary device.

Eight people were hospitalized. The victims ranged in age from 52 to 88. What should have been a moment of peaceful assembly turned into a scene of terror.

This wasn’t an isolated incident. It was a flashpoint in a larger crisis—a mirror held up to our national dysfunction. A moment that reminds us how urgent it is to take hate and racism seriously in all its forms. But we cannot address that urgency with selective memory or politically convenient outrage. We must call out hate and racism no matter who it targets or who commits it. We must be clear: violent ideology is not solidarity. It is terrorism.

And this moment demands more than silence, more than soft statements, more than trending hashtags. It demands courage. It demands accountability.

Because this is not just a tragedy. It’s a warning.

It’s also a reflection of something far more widespread than we often admit: racism in America isn’t just alive—it’s on fire.

The flames didn’t start in Boulder. They’ve been smoldering in school board meetings, in campaign rallies, on cable news, in college dorm rooms surveilled for protest, and in social media echo chambers that reward outrage over empathy. They erupt when public officials court white supremacists one day and claim to defend HBCUs the next. They scorch when real pain is reduced to partisan ammunition. And they spread when we ignore them until someone, somewhere, picks up a torch.

The Privilege of Never Having to Know

To study and discuss anti-Semitism is one thing. To live it is another. You can read books on the Holocaust. You can analyze hate crime data. You can quote Elie Wiesel. But you will never feel what it’s like to see swastikas spray painted in your neighborhood. Or see your children’s synagogue under armed guard. Or have your identity publicly questioned because you dare to speak up for peace—or for Palestine or anywhere else.

I can explain it. But I cannot feel it. And that difference matters.

One of the greatest honors of my life was being invited by members of the Jewish community to participate in the March of the Living—a journey to Poland that brings together Holocaust survivors, students, and allies to walk from Auschwitz to Birkenau. I accepted with humility and deep gratitude. The invitation itself was a gesture of profound trust—an acknowledgment of shared struggle and mutual respect.

Sadly, the trip was canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. But the meaning of that invitation has stayed with me. Even though I never walked those haunted paths, I carry the weight of what it meant to be asked to witness—to be present for memory, for mourning, for moral clarity.

That experience reminded me of what I can never truly access. I cannot feel the generational pain of Jewish families fractured by genocide. I cannot know the fear that lingers in the marrow of a people who have survived pogroms, forced exile, and systematic extermination. I cannot wake each day wondering if my very identity will be used as a justification for someone else’s violence or someone else’s war.

But I do know something about hate and racism.

Recently, in broad daylight on a sidewalk in New York City, a white man looked me in the eye and called me the n-word. No context. No conversation. Just raw racism hurled like a brick. It wasn’t the first time. But it never stops stinging. It doesn’t just hurt—it hollows. It reminds you that no matter your titles or accomplishments, no matter how far you’ve come, to some people you will always be nothing more than their projection of hate and racism.

I know what it means to feel vulnerable in public. To have your body politicized, pathologized, and policed. I know what it means to have your children carry the weight of being seen as threats before they’re seen as students. I know what it means to watch justice delayed, denied, and distorted—over and over again.

But I do not know what it means to be Jewish in a world that has, over centuries, treated Jewishness itself as a target. I do not know what it is to carry Holocaust trauma in your family tree. I do not know what it is to see your faith reduced to a soundbite, or your community co-opted for agendas you never consented to.

So we must listen. Show up when we can—not just when it’s politically convenient, but when it’s hard.

You Cannot Fight Hate Selectively

What we’re witnessing right now is a dangerous hypocrisy: The same politicians who ban books about the Holocaust are now acting as if they’re the protectors of Jewish people. The same elected officials who court white nationalists, who nod along with “great replacement” conspiracies, who pander to groups that chant “Jews will not replace us”—these are the ones now claiming moral high ground.

They don’t care about anti-Semitism. They care about control.

When they say they’re against hate, ask: Against whose hate? And against whom?

Because you cannot fight anti-Semitism while platforming Islamophobia. You cannot defend Jewish students by doxxing Palestinian ones. You cannot honor the legacy of Jewish survival while silencing the cries for justice from Gaza to El Salvador.

This is not solidarity. This is co-optation.

We see the contradiction on our campuses and in our Congress. Students holding vigils for lives lost in Gaza are met with police in riot gear. But neo-Nazis marching in Charlottesville are met with permission slips and Trump’s “some very fine people” platitudes. Jewish communities are told to be grateful for support from those who align with American Nazis—so long as they denounce Palestine loudly enough.

We’re asked to pick a side. But real justice doesn’t come from choosing between who deserves empathy. It comes from dismantling the systems that dehumanize all of us.

We must not let the language of justice be twisted by opportunists. True justice requires clarity—and consistency.

The Role of Non-Jewish Allies: Less Talking, More Risk-Taking

If you are not Jewish, and you truly want to be in solidarity, we have to be anti-racist. Start doing the hard work of challenging it—in your family, your workplace, your political party. Real allyship is inconvenient. It costs you something. It puts you at odds with power, not in bed with it.

Being a true ally to Jewish communities means recognizing the full diversity of Jewish life—Mizrahi, Black, secular, Orthodox, queer—and resisting the urge to flatten them into political pawns. It means fighting anti-Semitism on the right and the left. It means condemning violence against Jews not just when it trends, but when it festers in the corners of society where you could benefit from the silence.

And it also means standing against all forms of hate—against Muslims, immigrants, LGBTQ+ people, Black communities, and others who are dehumanized and demonized to score cheap political points.

This is what Boulder should teach us. This is what history demands of us.

We can’t afford to have selective outrage anymore. The stakes are too high. The violence is too real.

The Limits of Explanation—And the Power of Action

Boulder is not just a city in mourning. It’s a mirror held up to our national failure to confront hate and racism before it ignites. It’s a reminder that unchecked rhetoric becomes real violence. That political polarization can be deadly. That silence is complicity. You can explain anti-Semitism. You can study it. Teach it. Cite it. But if you’ve never lived with it, you don’t get to define it alone. You don’t get to exploit it. You don’t get to substitute your voice for those who carry its weight every day. We need fewer explainers. We need more protectors. More listeners. More fighters who know the difference between allyship and appropriation.

So if you, like me, are someone who cannot experience anti-Semitism—but still insists on standing against it—do so with humility. With accountability. And with action that speaks louder than your explanations ever could. Because no one should have to walk down the street afraid of a slur—or a bullet. Not in D.C. Not in New York. Not in Tel Aviv. Not in Gaza. Not in Boulder. Not anywhere.

The Final Word: Moral Courage, Not Moral Cowardice

And that brings us back to what Professor Lawrence Tribe recently observed.

He said we are living in a time when anti-Semitism is rightly being condemned—but too often, not by those who genuinely care about Jewish people. Instead, it’s being used as a blunt-force political weapon. These defenders show up only when they can weaponize the pain of Jewish communities against student protestors, against Black or Muslim activists, against free speech, or against movements demanding Palestinian human rights.

Let me be clear: Racism and anti-Semitism is real. It is dangerous. It must be confronted—always. But confronting it requires something deeper than tweets and talking points. It requires a commitment to Jewish people, not just Jewish pain when it’s politically useful.

The question now is: Will we rise to that standard?

Or will we keep pretending that cherry-picked outrage is enough?

Leave a comment