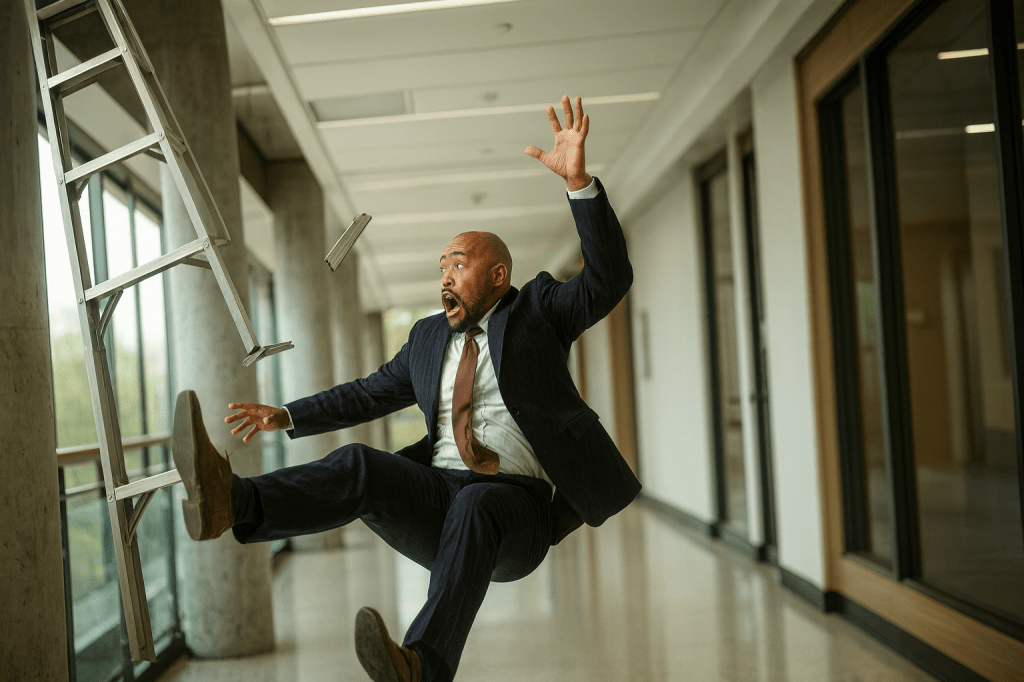

Climbing ladders in life is supposed to be the surest way to more impact. For example, in universities, the ladder is mapped out with precision: start as an assistant professor, earn tenure, advance to associate professor, then full professor. From there the rungs shift to leadership—program chair, department chair, dean, provost, and if you’re lucky, president. Each step is advertised as progress, prestige, and engagement.

But anyone who has actually climbed the career ladder knows the view rarely matches the brochure. The rungs don’t always rise. Some bend. Some break. And some leave you more exposed than elevated. I know because I’ve lived it. I was a program chair and vice-chair at the University of Texas at Austin, director at California State University Sacramento, dean at the University of Kentucky. Later, I became provost at Western Michigan University. And here’s the truth most people will never say out loud. We’re told the ladder is always worth climbing. Keep moving up, keep reaching higher. The next rung must be better than the last, right? But the higher you go, the less true that becomes. Sometimes the climb brings more pressure, more conflict, stress, and less fulfillment.

Take universities as a case in point. On paper, provost looks like the ultimate power position, second only to president. But the reality is different. Deans are insulated in ways provosts are not. Deans have direct, visible impact on students and faculty. They can build legacies that endure. Provosts, by contrast, are structurally exposed, pulled into unending conflicts, and almost always destined for a falling out with their president.

This isn’t about competence or ambition. It’s about insulation, impact, and sustainability. The truth is simple: climbing the ladder in life doesn’t guarantee a better view. And sometimes the rung you left behind was the stronger, wiser, better place to stand all along.

The Energy of the Deanship

When I was dean at Kentucky, I felt energy every day. The job was demanding, but it was rewarding. I could recruit faculty and watch their scholarship transform departments. I could design programs that attracted students and addressed community needs. I could forge partnerships with schools and nonprofits and see doors open for students in real time.

The scope of responsibility was large but bounded. I knew where my accountability began and ended. My job was to lead the college. Success was measured by student enrollment, faculty growth, fundraising, and community engagement. The wins were visible. The feedback loop was short. When something succeeded, everyone in the college felt it. When something failed, we learned and adjusted.

That clarity gave me energy. I could lead with vision and see it take shape. I could advocate fiercely for my faculty and students without being crushed by competing institutional priorities. The insulation of the dean’s role mattered.

The Provost’s Reality

Becoming provost at Western Michigan seemed like the natural next step. The title suggested authority. The scope suggested influence. I was, after all, the chief academic officer of the university. But the reality was very different.

The provost sits in a perpetual crossfire. Presidents and trustees push for growth, visibility, and metrics. Deans push for resources and autonomy. Faculty push for governance and investment. Vice presidents push agendas for their own divisions. Every constituency sees the provost as their champion or enemy.

The job is structurally designed for conflict. You do not have the insulation that a dean enjoys. You do not have the autonomy to act without constant negotiation. What looks like leadership on paper becomes crisis management in practice. Much of the work is about mediating disputes, enforcing policy, and defending and taking heat for decisions that were not your own.

The President–Provost Trap

Here is the truth that higher education rarely says out loud. Almost every provost eventually falls out with their president. It is usually not because provosts are incompetent— they rose through the ranks very competently to get there. It is because the relationship is fragile and not real by design.

Presidents do not see provosts as partners with independent vision. They see them as extensions of their own agenda. When the provost aligns perfectly, all stays well. But alignment is never permanent. A provost who advocates too strongly for faculty or students or staff or unions is seen as disloyal. A provost who pushes equity too forcefully is seen as political or as an “advocate” as one vice president put it. A provost who questions a president or his/her/they or their VPs’ initiatives/bad ideas is seen as “difficult.”

At that point the relationship begins to fray. And when it does, it is almost always the provost who goes. Presidents survive. VPs survive. Provosts move on. I have lived this. I have watched it happen to colleague after colleague. Nearly every provost I know has had some version of this story. We whisper it to each other in conference hallways, but we rarely admit it publicly. Today I am saying it clearly.

The Equity Trap

Equity work reveals this dynamic even more starkly. As dean, I had space to advance equity. I could redesign programs, create teacher pipelines, and recruit faculty of color. I could redirect resources toward justice and innovation. The insulation of the dean’s office gave me cover to lead boldly.

As provost, equity work became harder. Every initiative had to be coordinated across colleges where deans often push back, debated in governance structures, and signed off by the president. Push too hard for equity and I risked my relationship with these stakeholders. Hold back and I betrayed my mission and calling. The balancing act was constant. The very work that energized me as dean became constrained and politicized as provost.

Prestige Without Protection

The provost’s role is assumed to carry greater prestige. It is the second-highest academic office, after all. But prestige without protection is a trap. Provosts are invisible when things go well and hyper-visible when things go wrong. Every budget gap, every accreditation issue, every controversy falls on the provost’s shoulders.

Deans, by contrast, enjoy prestige that matters most. They are the face of their college to alumni, donors, students, and community partners. They are celebrated when their programs succeed. Their accomplishments are tangible and visible.

This is also why many long-serving deans leap directly to the presidency. They don’t get caught in the provost trap. A long-serving dean already has what boards want in a president: a visible track record of growth, fundraising relationships, external partnerships, and the political capital that comes from delivering results people can see. The presidency rewards outward-facing leadership, vision, and resource generation, skills deans practice every day, while the provostship often functions as nakedly exposed middle management, absorbing conflict without the insulation or authority to match. For a seasoned dean, the straight line to president can be safer, saner, and ultimately more impactful than a detour through the provost’s office.

Why I Love What I Do Now

But honestly, I love what I am doing right now even more than either dean or provost. My work feels urgent, purposeful, and connected to the communities I care about most. I am advocating for equity in ways that ripple beyond a single campus. I am preparing to teach my classes, which grounds me in the very reasons I entered higher education in the first place: the joy of helping students think differently, imagine boldly, and act with courage.

I am giving keynotes that reach thousands of educators, leaders, and policymakers across the country, sparking conversations that matter. I am consulting with organizations that want to center equity not as a slogan but as a practice, embedding justice into their programs and strategies. I am working alongside community organizations that are on the front lines of change, supporting them as they build capacity and resilience.

Beyond that, I am contributing to national media, appearing on podcasts, and giving interviews to print outlets that amplify these ideas to wider audiences. I am shaping narratives that influence public understanding of education, equity, and leadership. And I am even exploring a modest collaboration with former Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona, a project that underscores how this work resonates at the highest levels of national dialogue.

This season of my career is more than a professional pivot. It is a return to purpose. It is 1000% more fulfilling and 1000% less stressful than life as a provost. I no longer spend my days in bureaucratic tug-of-wars or meetings where the outcomes are predetermined. Instead, I spend them building, advocating, teaching, and speaking, work that restores energy rather than drains it, and work that feels worthy of the climb, no matter what rung I am standing on.

The Conversation We Need about Climbing

Climbing the ladder is one of the most enduring myths in professional life. From the earliest stages of our careers, we are taught to see each rung as a marker of progress and impact. In universities, it is the move from assistant to associate to full professor. In corporations, it is the shift from manager to director to vice president to CEO. In politics, it is the slow march from local office to state legislature to national prominence. In every arena, the story is the same: keep climbing, keep reaching, never stop. The next rung is always worth the struggle.

But ladders are not built equally, and not every step leads to greater fulfillment or impact. Some rungs are sturdy and allow us to grow. Others are warped, brittle, or broken. Sometimes the climb takes us higher in title but lower in purpose. Sometimes prestige comes without protection, authority comes without freedom, and advancement comes without joy. The corner office can be lonelier than the cubicle. The cabinet seat can be more constraining than the city council chair. The provost’s desk can be more exposed than the dean’s.

The truth is that careers are not linear. They are ecosystems of possibility, full of roles and opportunities that energize us in different ways. The real measure of progress is not how high you stand on a ladder but whether the work itself gives you energy, sustains your values, and allows you to make a difference that lasts.

For some, that will mean continuing to climb. For others, it will mean staying put on the rung that feels strong, steady, and aligned with purpose. And for many, it will mean stepping off the ladder entirely, choosing instead to build something of their own, on their own terms.

The point is not whether you climb or stop climbing. The point is whether you are standing on ground with humans that empower you to thrive. What matters most is not the height of the climb but the strength of the ground beneath your feet.

Julian Vasquez Heilig is a nationally recognized policy scholar, public intellectual, and civil rights advocate. A trusted voice in public policy, he has testified for state legislatures, the U.S. Congress, the United Nations, and the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, while also advising presidential and gubernatorial campaigns. His work has been cited by major outlets including The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Los Angeles Times, and he has appeared on networks from MSNBC and PBS to NPR and DemocracyNow!. He is a recipient of more than 30 honors, including the 2025 NAACP Keeper of the Flame Award, Vasquez Heilig brings both scholarly rigor and grassroots commitment to the fight for equity and justice.

Leave a comment