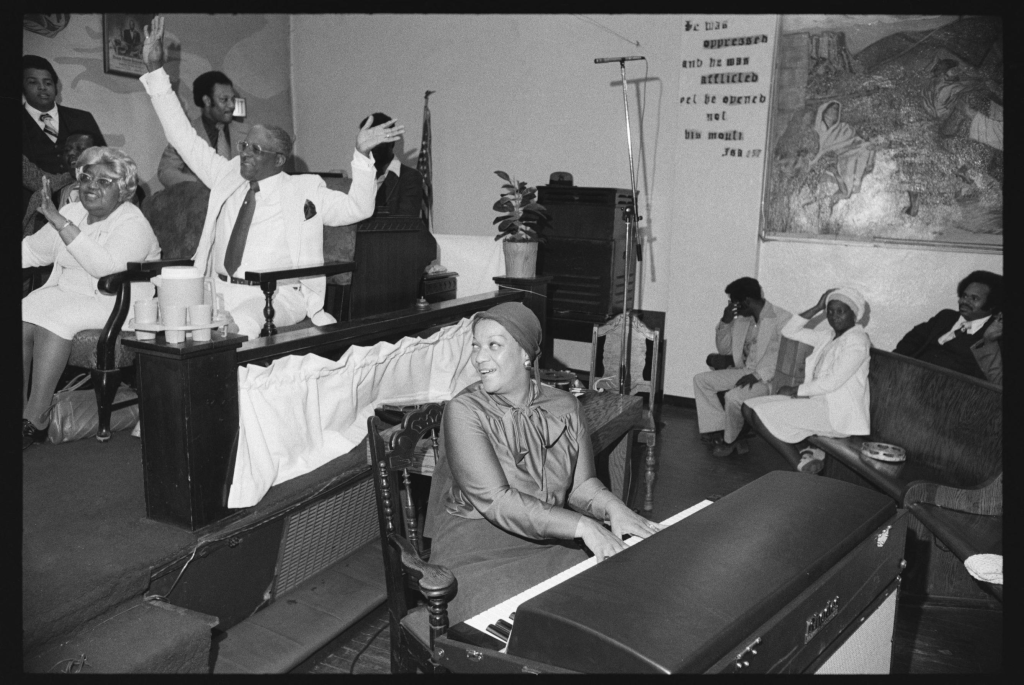

I remember hearing “This Little Light of Mine” long before I truly understood it. I was a small child in a church in the early 1980s, surrounded by families who carried both joy and heaviness in their voices. The song moved through an upstairs room in a way that felt familiar even before I could comprehend its message. It gave me a sense of belonging that did not require explanation or credentials. It was part of the emotional language of the community that raised me.

Those early memories did not fade as I grew older. They followed me into classrooms, into leadership roles, and into difficult professional spaces where the stakes were higher and the pressures heavier. Even when I did not consciously think of the song, something about its message lived inside me. It taught me that strength did not always shout. Sometimes strength simply refused to disappear. The song’s quiet clarity shaped my understanding of what it means to persist.

Years later, as Dean of the College of Education at the University of Kentucky, I found myself returning to this song again. Not out of nostalgia, but out of necessity. In rooms where we met to discuss equity, courage, and institutional transformation, the song became a compass. It guided decisions that were often complex and sometimes contentious. The message was simple but not simplistic. Leadership is not about grandeur. It is about light. “There’s something about people who are motivated to make the world better.”

The Rumors, The Research, and the Record: What Snopes Found

For many years, people have said that “This Little Light of Mine” was a slave spiritual. The rumor has circulated in newspapers, classrooms, community conversations, and even in church settings. It seems believable because the song carries the emotional weight often associated with spirituals. The melody had the kind of resonance that makes listeners assume the song came from the deepest corners of African American history. Yet when Snopes conducted a detailed historical investigation, the evidence for this has not yet been found.

Snopes reviewed old hymnals, newspaper archives, spirituals databases, the Library of Congress, Stanford University collections, and other authoritative sources. They did not find any record of this song existing during the era of slavery. It did not appear in published lists of slave spirituals or known catalogs of antebellum music. It did not match the archival traces that usually accompany songs from that era.

Several sources they found suggested the song may have originated in the 1920s. However, Snopes noted that even this decade is not firmly established. Some hymnals referenced “circa 1920,” but those texts are difficult to access today. The earliest newspaper reference Snopes found was from 1931, when the Mt. Olive Missionary Baptist Church in Los Angeles listed the song in a service announcement. The article described the song as a blessing to the congregation, showing that it was already circulating within Black worship spaces by that time.

Part of the confusion stemmed from the longstanding belief that Harry Dixon Loes composed the song. Loes was a white gospel musician who taught at Moody Bible Institute and arranged hundreds of Christian pieces. While he popularized a version of the song, researchers at Moody said they found no evidence he wrote the original. Old articles from the early twentieth century discussed Loes’s work without mentioning the song. This suggests his role was one of arrangement and distribution rather than creation.

A Song Without a Single Author but With a Collective Soul

The absence of a clear historical origin does not weaken the song’s significance. If anything, it reveals something deeper about the way music moves within Black communities. The fact that “This Little Light of Mine” may not be a slave spiritual does not mean it was disconnected from the spiritual tradition. Black communities have adapted it, transformed it, and infused it with the emotional and theological weight of our lived experiences. In that sense, the song gained its soul not from its composer but from the people who carried it.

Music within African American life has never been confined to sheet music or formal authorship. Songs moved by oral tradition. They were shaped by gatherings, revival meetings, kitchen-table harmonies, and the private moments when people needed something to hold onto. Music was a way to carry theology without textbooks. It was a way to carry grief without breaking. It was a way to preserve memory without written archives. Songs often took on new layers of meaning as they passed from voice to voice.

“This Little Light of Mine” entered that tradition and found a home there. Whether it began in a Sunday school classroom or a small church publication, it became a spiritual in practice even if not in origin. Black people made the song what it is. They interpreted it through the lens of survival. They added harmonies shaped by struggle. They infused it with hope that refused to collapse under pressure. The song traveled from worship spaces to schools, community programs, and eventually to the very heart of the Civil Rights Movement.

No matter who wrote the first version, the song’s deeper authorship belongs to the people who used it as fuel for liberation. Its life did not start on a page. It started in the hands of a community that understood how to turn simple language into spiritual force. The song carries that inheritance more faithfully than any historical record could.

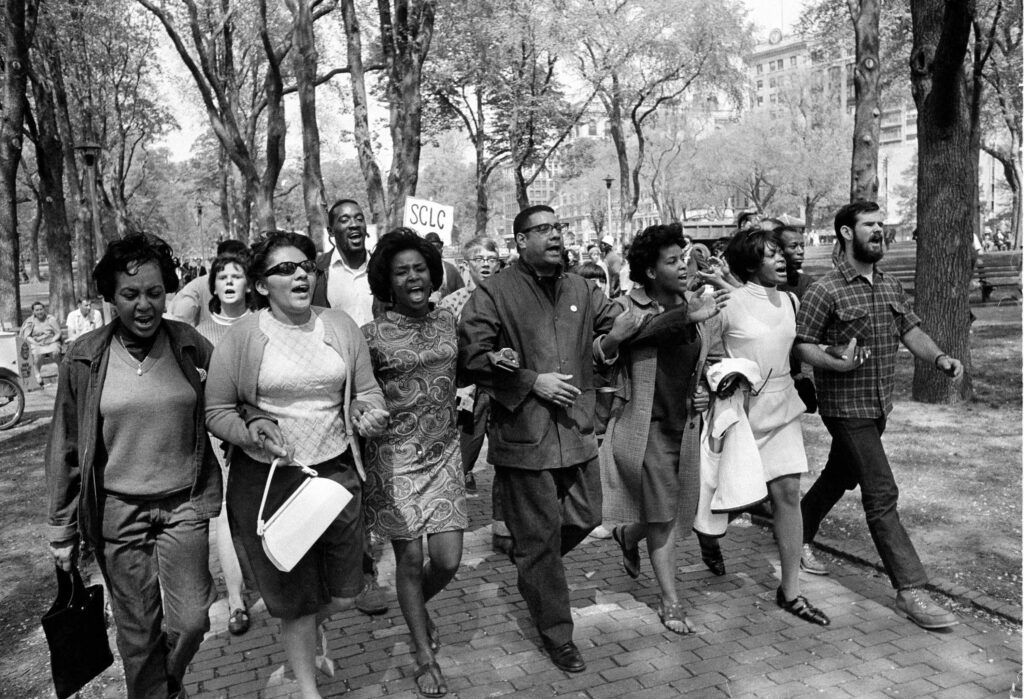

From Church Pews to Freedom Marches

“This Little Light of Mine” became a freedom song not through publication but through practice. During the Civil Rights Movement, the song appeared in marches, mass meetings, sit-ins, and jail cells. Young people used it to steady one another during violent confrontations. Adults used it to prepare their spirits before facing police and mobs. Children sang it while walking into segregated schools. Its simplicity made it accessible, and its message made it indispensable.

Fannie Lou Hamer sang the song with a kind of clarity that could anchor a room. She sang it after being beaten by police for attempting to register to vote. Her voice carried the song into national consciousness because she refused to let suffering silence her. Bernice Johnson Reagon and other movement leaders used the song to open gatherings and activate collective energy. It created unity in moments when individuals could have easily become overwhelmed.

During the 1963 Children’s Crusade in Birmingham, students arrested for nonviolent protest filled jail cells with the chorus. Their voices echoed off concrete walls, forming a shield against despair. The song gave them something to claim at a moment when the state attempted to strip them of identity and dignity. This was not entertainment. It was strategy. The song offered a stable center in unstable environments.

The reason the song worked so powerfully is that it affirmed something essential. It reminded people that their light still had value even when the world insisted otherwise. It told them that oppression could not extinguish what had been placed within them. The song became a declaration that dignity survived every attempt to erase it. That declaration helped people hold the line in moments where surrender would have seemed easier.

Why the Song Still Endures

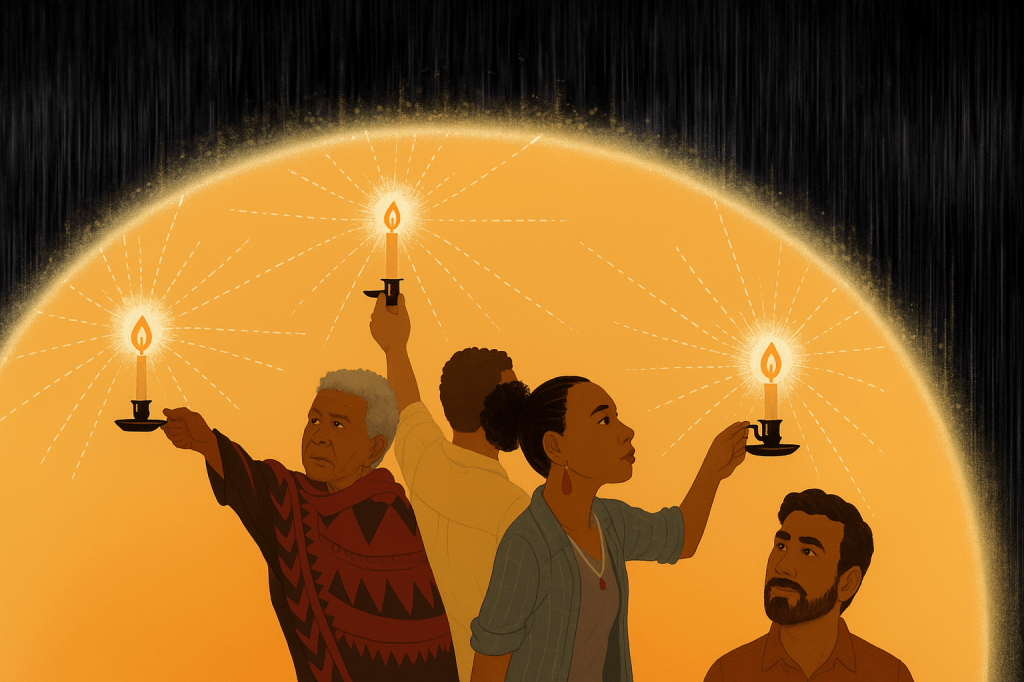

“This Little Light of Mine” has lasted because it speaks truths that remain relevant. The first truth is that every person carries a light. This message does not depend on rank, wealth, or social position. It affirms inherent worth at a time when society repeatedly attempts to categorize value. The song offers a corrective to structures that elevate a few while limiting many. It insists that every life contains a spark that is meant to be honored.

The second truth is that light is meant to be shared. Light confined to a corner does not fulfill its purpose. When people extend their light toward others, they expand possibility and connection. The song teaches that the world becomes brighter when more people participate in its illumination. Sharing light is a communal act rather than an individual performance. It invites people to contribute to a collective good.

The third truth is that shining is a form of resistance. In environments that reward silence, shrinking, or conformity, choosing to shine expresses a different kind of power. It does not require aggression. It requires clarity. It does not require perfection. It requires presence. It confronts systems designed to diminish certain voices by refusing to disappear. That refusal has shaped every major movement for justice in this nation.

These truths are why the song continues to matter. They are why children still learn it, churches still sing it, and activists still invoke it. The song carries a moral orientation that transcends its origin story. It calls people to live with purpose even when circumstances make that difficult.

The Light We Need Now

We live in a period that demands renewed attention to light. The pressures that silence truth have evolved in our political envornment, but the impact of that silence is no less destructive. Communities still face inequitable policies from ICE, banks, police, courts, and other actors as institutions still struggle to confront their histories. People still encounter pressure to soften their convictions for the sake of comfort. In such a moment, the message of this song becomes deeply relevant again.

There are conversations that cannot be postponed. There are injustices that cannot be overlooked. There are young people who need to know that their contributions matter. Light becomes both a metaphor and a method for how we navigate the present. Shining requires intention because the forces of distraction and division remain persistent. It requires humility because leadership rooted in ego rarely produces lasting change. It requires courage because telling the truth often carries consequences.

Yet we are part of an American lineage that has faced greater challenges and still carried light forward. Every generation before us confronted forces that tried to dim their brightness. They responded with resilience shaped by community rather than isolation. They did not allow fear to define their contribution. They honored their light by using it. That history is not distant. It is an inheritance.

Lighting a Fire in Every Heart

This is why I return to this song. It strengthens my belief in what the United States should be. I want to help create conditions where every person feels empowered to shine rather than pressured to withdraw. I want to support students who bring vision and courage into spaces that were not built for them. I want to contribute to communities that prioritize integrity over convenience.

Imagine a society that celebrated the light in every person. Such a society would support creativity rather than suppress it. It would value truthfulness in politics and public leadership. It would cultivate environments where young people feel free to explore their gifts and values without fear. It would recognize that the purpose of power is to illuminate rather than overshadow. This vision is not idealistic. It is necessary.

Every movement for justice began with individuals who decided to shine where they stood. Their willingness to do so created pathways for others. That responsibility now belongs to us. It asks for more than belief. It asks for action. It asks for the choice to step forward even when uncertainty lingers. It asks for the commitment to use one’s light in ways that strengthen the collective.

Let this be the time in history you lift your light without hesitation. Let this be the moment you choose clarity over concealment. Let this be the season you embrace the fullness of your purpose. Let your voice, your work, your courage, and your character shine for others to see. Let it shine in every room you enter. Let it shine through every challenge you face. Let it shine because the world needs it now more than ever.

Let it shine. Let it shine. Let it shine.

Julian Vasquez Heilig is a nationally recognized policy scholar, public intellectual, and civil rights advocate. A trusted voice in public policy, he has testified for state legislatures, the U.S. Congress, the United Nations, and the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, while also advising presidential and gubernatorial campaigns. His work has been cited by major outlets including The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Los Angeles Times, and he has appeared on networks from MSNBC and PBS to NPR and DemocracyNow!. He is a recipient of more than 30 honors, including the 2025 NAACP Keeper of the Flame Award, Vasquez Heilig brings both scholarly rigor and grassroots commitment to the fight for equity and justice.

Leave a reply to Dr. Julian Vasquez Heilig Cancel reply