Teach For America recently announced that they were sending more teachers of color than ever before to teach for short term stints in America’s schools. They expect to be lauded for this.

What is Teach For America? Read here.

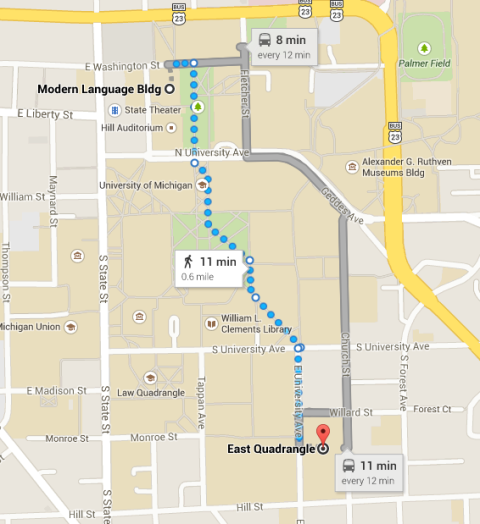

Have you ever experienced a situation where you were knowingly or unknowingly unprepared? How did it make you feel? My first year at the University of Michigan Ann Arbor was a rough year. I had an introduction to psychology course in the Modern Language Building (MLB) building which was on the other side of campus from my East Quad dorm.  Now I realize that the google map above says its only an 11 minute walk, but Michigan weather is not the most hospitable in January and February. The first day of class, the professor (whose name I still remember), told us that we didn’t have to go to his weekly lectures, we could read the book (which he had authored) and do fine on the midterm and final exam— the only metrics important for the grade in the class. So, two weeks into the class the 300 person lecture hall was basically empty. By week three, it was only myself and about 20 other students who would actually attend lecture. By February I stopped going because it was just too cold. Well, the professor changed his mind in the middle of the semester and declared that he would now include questions on the tests that would only come from information given in lecture. I was in shock. The midterm was the following week and I hadn’t attended lecture in a month because the professor had told the class during the first meeting that it wasn’t necessary. Was this some sort of psychology experiment? It wasn’t. I received a C on my midterm because I was not able to answer the questions from the newly required lectures. I felt guilty that hadn’t gone to lecture. I felt like a failure because it was the first C I had ever received in my life on an exam at any level of education. In essence, I was set up for failure.

Now I realize that the google map above says its only an 11 minute walk, but Michigan weather is not the most hospitable in January and February. The first day of class, the professor (whose name I still remember), told us that we didn’t have to go to his weekly lectures, we could read the book (which he had authored) and do fine on the midterm and final exam— the only metrics important for the grade in the class. So, two weeks into the class the 300 person lecture hall was basically empty. By week three, it was only myself and about 20 other students who would actually attend lecture. By February I stopped going because it was just too cold. Well, the professor changed his mind in the middle of the semester and declared that he would now include questions on the tests that would only come from information given in lecture. I was in shock. The midterm was the following week and I hadn’t attended lecture in a month because the professor had told the class during the first meeting that it wasn’t necessary. Was this some sort of psychology experiment? It wasn’t. I received a C on my midterm because I was not able to answer the questions from the newly required lectures. I felt guilty that hadn’t gone to lecture. I felt like a failure because it was the first C I had ever received in my life on an exam at any level of education. In essence, I was set up for failure.

This story brings me back to Teach For America, which sends well-meaning college graduates and other non-traditional teachers into the the classrooms of poor students of color and whites for a two year teaching commitment. The Teach For America model has been to provide five weeks of training before these inexperienced teachers hit the classrooms in some of the most impoverished neighborhoods in the United States. They call their approach and the recruitment of short term teachers of color “civil rights”…. but is it? I recently received this message from a Teach For America alumna:

My name is Annie Tan– I’m on your Facebook page and have been reading your blog for a number of years now. I’m responding to your post on Facebook about people of color in TFA feeling guilty/guilt. (As an aside, thanks for talking to the democrats in Texas a few days ago- your video was on point, respectful but holding no punches.) I’d like to share my thoughts about my TFA experience, specifically from the lens of a person of color. Forgive me for the long email I am about to send, but I feel it’s imperative to send you a background of my own relation to my identity as a person of color before I can share my experience with Teach For America. I am sharing lots of aspects on diversity that were explicit in TFA training and within my own teaching, and I hope I don’t go on too many tangents. I put so much detail because I have been thinking about these issues for three years and hope they can be useful.

(I would love for you to blog your Teach For America story too, email me at jvh@alumni.stanford.edu. It can be anonymous if you suspect that Teach For America will punish you)

Here is Annie Tan’s story:

Introduction

I was an urban studies major and elementary education program member at Columbia University. I knew there was a hiring freeze going on in NYC public schools, and I also realized I no longer wanted to teach elementary education. Not wanting to go through another program, I decided TFA was a viable route for me. I thought I would be replacing someone who would not know as much about education as me (after all, I’d gone through an ed program!). I also thought having a strong Asian in the group would be a good thing. (TFA was recruiting heavily amongst groups of color such as the Asian American Alliance on campus, so I knew I had a good shot of getting into the corps).

I have had my gripes about TFA from sophomore year of college. Learning about the neoliberal education reform movement, lack of teachers of color in the profession, TFA’s support of charter schools, funding from questionable sources who may have ulterior motives in education other than the education of all students, factored into my criticism of TFA. I didn’t want to be a savior in education- I just wanted to teach. But I guess I did fall into a savior mentality as I joined- I thought I was going to be so much better, that I was going to save my students. I was very smug about it, until the realities of the first year beat me down.

I have never really identified with TFA. As a teacher, I never said to parents I was a TFA teacher. Teachers in my building knew, which helped gain sympathy in the beginning for my lackluster ways, but increasingly less so. I never put it on my resume (except during hiring time at Institute, where we were all required to). I thought TFA was doing an injustice to students, but I thought, being a lone teacher, that I was making the difference I wanted to. I went into it thinking TFA had no tie to my school community. However, I was wrong when I realized 2/3 of teachers in my school were TFA corps members or alum. I tried to shy away from it, but being in TFA was an essential part of my identity as a first-year. And the students knew- “Ms. Tan, will you be our teacher next year?” Were the first words I heard from a student, hinting at the high turnover at the school.

I worked in a black neighborhood, in a school that had occupied the space of a neighborhood school before it. I constantly felt guilty about being a teacher at a charter school replacing this beloved school. I heard from parents all the time, ” I like the school, but I hate how the teachers always leave.” I always wondered if the teachers would leave if they were part of the community. I also heard, “We all went to Hardigan back in the day. Now we don’t have that sense of community.” Our charter school, with its high turnover and many TFA teachers who didn’t come from the community, we’re making it tough for this community to feel solidarity.

The Experience

I felt strange and guilty being a person of color from an Asian perspective. While I am a low-income, bilingual, daughter of immigrants who don’t speak English, and born/raised in a segregated Chinatown in NYC, I also had lots of privileges growing up that the students I taught my first year with TFA did not have. I was Chinese, meaning people thought I was good at math and saw me as someone who could succeed. People have always pushed me forward, giving me the academic language to push forward and achieve what I have. I ended up at Columbia, but that furthered a self-hatred of my low-income, born of immigrants background. It was when I was at Columbia though that I discovered the term social justice, became a part of my Asian American Alliance, took ethnic studies courses, hosted our own versions of Freedom Schools at a social justice house, and lived in an intercultural resource center on campus for three years. I also was lucky to study under professors who believed in social justice- I went through an elementary teacher program through the Barnard-Columbia program and went to Central Park East II, a school which I believe was started by Deborah Meier.

I think the largest part about being Asian in a country like this is that we Asians are always cast aside in major conversations about race. I’m always deemed to have the best of POC worlds- I look the most white, speak white, can pull it off, because I’m a model minority. I don’t believe this, of course, but I need to know what others view me as in order to walk in the world. All of that affects how I interacted with others and my own identity as a TFA corps member.

When I started TFA in Chicago, I was new to the city- I had some background about Chicago due to my urban studies major at Columbia where we studied Chicago extensively. I had decided to switch to special education while student teaching at Columbia because I felt a greater rapport with special needs students. On the first day, we were welcomed- we were going to be the teachers of high expectations, and that’s what kids on the south and west sides of Chicago didn’t have- teachers who would hold them to high standards and expect the most of them. Problem was, there was no context given about Chicago- its history, its development, nothing. Everyone clapped, including me- I knew we were in for a ride and I couldn’t afford to ask questions then about what Chicago looked like because we only had five weeks to train. I would learn about Chicago race relations later, I told myself. It wasn’t TFA’s responsibility. Right?

Another thing in the first day of institute were these strange tables they had us arrange in. We were to tell these complete strangers why we were here, major struggles we had, and tell a major part of ourselves. Story after story of white privilege and savior complexes, in my mind, abound. Then I told my story- about my childhood, how my uncle was Vincent Chin, who was killed in a hate crime, and how I knew I wanted to make sure his legacy was to push for an anti racist society. I didn’t shut down conversations, but I didn’t call people out, either, at these sessions.

There were also these DCA sessions we were involved in, talking very generally and broadly about race- they were constantly white/black conversations with no context of Chicago, no real mentions of Latinos or Asians, let alone even more marginalized communities. These were tedious for everyone. We knew these conversations about race were extremely superficial but we never called them out. We were too focused trying to learn how to teach. To this day there are diversity town halls to address the issue of race openly in a discussion format, but that’s only for members seeking information, clarity, and answers to diversity questions in the corps and not necessarily addressing diversity across TFA.

Affinity groups were one way TFA tried to get people who identified as black, Latino, queer, and Asian in small groups and talk about their experiences. I met a number of Asians here and was generally on the lookout for people of color to be allies with me during the first year of teaching. I had read Sonia Nieto and others’ works- I knew being a teacher of color was going to be hard work, and I was going to need allies.

By the end of institute I had met twenty people of color who would be in the Chicago corps. Of those twenty, though, ten had left by the time institute ended. (I, along with at least five more teachers of color I would later meet, were fired or let go from our teaching positions by the end of the first school year.) Something I have always wondered is attrition rates in TFA and how many of those people are teachers of color. I imagine they would be much higher rates of attrition for people of color than for non-POCs.

Then I began as a charter school special ed elementary teacher for grades K, 2, 3, and 4, adding 1st grade by the end of the school year. I was an inclusion teacher as well as a resource teacher for reading and math. While teaching that first year I thought my POC status and my low-income status as a kid would help me understand and build rapport with my students. I did generally have a good rapport with my students, but to the point, at least in the terms of admin and co-teachers, that I was having low expectations from my special education students. I’m sure I had low expectations partly because I was teaching five grade levels with little/no training in special education. I think though that my experience as a POC with low income made me realize more realistically what my students could and could not accomplish and how I could get them to where they needed to be- WHILE also accommodating for social, emotional, and behavioral needs. I was feeling very guilty about lowering my expectations, according to the people I was working with- was I really to blame here, or am I just seeing what is on the ground and actually advocating for my students by meeting their needs? This was the constant fight that year, alongside having a ridiculous work load and going to graduate school at nights.

But then, as an Asian, even if I were low-income, how could I possibly relate to my students? I was never told by anyone that I wasn’t like them, but I always had this internal monologue going in my head, saying, “Annie, you are not black or Hispanic- this is a different experience.” I constantly doubted the legitimacy of my own experience as a person of color- and then doubted my ability to feel empathy, solidarity with other people of color. I didn’t live on the South Side, I didn’t grow up in Chicago, so how could I relate? And how could the kids relate to me? Part of it was that I put up a barrier- no one at school knew this background of mine, and I didn’t open up. I was so scared that I wouldn’t look legitimate to my students- I was this big fake of a person of color, and I had so much more privilege and capital than them, even while growing up as a poor Chinese kid.

I was also pretty miserable in Chicago that first year. I had no real friend base, drinking heavily with other corps members, mostly white. Dad always calls every day, wherever I am, and the habit formed- he would constantly tell me how much he wanted me back home after my two-year stint, that the family needed people at home to translate, to provide rent, to provide money so my parents could finally retire. I was 700 miles away from home and felt so far. Why was I in Chicago? Because of some stupid hiring freeze in NYC? To try to avoid teaching in a charter school in NYC only to be placed In a charter school in Chicago? Not only was I not a great teacher, but I was disappointing my immigrant family who needed me, a boyfriend who needed more support from me (we broke up six months into me moving to Chicago), and my friends back home. I’m still tied to NYC, and my parents still want me home. I still wonder when, not if, I’ll move back there.

To be a teacher of color who believes in social justice in the classroom, I had to open up and call out what I thought was racist. At least, I felt I did, as a person of color who was aware. But how could I when I was, and am still, in my current teaching job at a neighborhood public school, the only (East) Asian teacher in my school? Would I be oversensitive when a kid asked me to speak Chinese, Japanese, to raise my eyelids, to show some Karate moves (all of which students have asked me in the past). Would I call out my colleagues who thought I was born in china? Would I call out teachers who I thought were being racist against students in the classroom? As someone who was hyper-aware of race, I felt myself overthinking it in the classroom, and realized I just needed to step up.

But that was a lesson too late in my first year of teaching, and I was fired before I was able to put that into action. The charter school fired me first, then TFA claimed it was my fault for not doing enough in my classroom to succeed- the charter school, they alleged, gave me enough support to succeed.

I am a teacher now in my own right, after getting a masters last year and teaching in a public school with a union (!!). I still face many of these issues, but after that first year of teaching I share where I am from, what my background is, and how that shapes me as a person. I still feel hyper-aware of race, especially when my race is not the race being discussed in Chicago (it’s a black and brown issue, after all). I find myself having to learn more by myself and asking a lot of questions in order to feel good about talking about race, like I will have to represent being Asian at some point and that I will need to feel ready at any moment to represent my race. (I hate that so much! the idea of representing my race.) I read much on black and Latino relations to make sure I am being respectful while also holding those realistic high expectations. I still struggle with much of this stuff, but I’m over the initial hurdles. Teaching is extremely rewarding now.

I do feel guilty now about being an example of someone who got into my current teaching through an alternative certification route. I know I was complicit in the firing of teachers from neighborhood schools, many of who were black veteran teachers, through my joining of TFA. I wondered in my first year if I should go back and get a real education before teaching. Maybe I should go back home to Chinatown, NYC, and teach in my home. The reality is that jobs are hard to get, and I felt I needed to stay in order to have a job. I hate that I had to go through TFA to get a job.

Today I am a teacher in my own right and I don’t identify at all with TFA. I do not feel bad about that.

Thanks for reading,

Annie Tan

I once heard that Teach For America alums finish their two year stints with “hubris” or “humility.” Thank you Annie for sharing your very personal experience with the readers of Cloaking Inequity. For all of Cloaking Inequity’s posts on Teach For America click here. Oh, and about that “undeniable” evidence of “positive” impact of Teach For America, read this and this.

Please Facebook Like, Tweet, etc below and/or reblog.

Want to know about Cloaking Inequity’s freshly pressed conversations about educational policy? Click the “Follow blog by email” button in the upper left hand corner of this page.

Twitter: @ProfessorJVH

Click here for Vitae.

Please blame Wendy Kopp for any typos. 🙂

It’s very interesting that Ann, a former TFA corps member viewed her “university classes as a complete waste of time,” and a means by which her debt was increased.

That same sentiment has been echoed by several Teach For America corps members that I have come to know, especially those who are first generation college graduates from lower to middle class families.

#1. Universities that partner with Teach For America somehow are viewed as the anchor of legitimacy– demonstrating that corps members are proactive and diligent in securing the education coursework, that they did not bring into the classroom when they were hired to teach.

#2. The idea that classes in the evening are going to replace practice in the classroom goes against the research literature. Debra Britzman’s (1991) Practice makes Practice (SUNY Press) notes that only consistent and supervised practice in multiple classrooms that offer several opportunities to teach small groups, large groups, differentiate instruction, manage behaviors, manage teaching time, plan multiple lessons, plan for accommodations of those lessons, assess student learning, revise how you teach the first time (when you wonder why students don’t understand your lesson), communicate with parents, communicate with other teachers, understand the culture of the community (which might be different from the one you were raised in) takes time in developing teachers. This differs from TFA’s 5-week’s of Corps Training Institute.

And, it differs from state regulations that mandate 12, 15, or 18 weeks required by aspiring cosmetologists who cannot practice without a license (AZ, CA, WA, ID, IL, CT, TX, …..)

#3. Teach For America’s partnerships are financial boosts for Colleges of Education that offer licensure after completion of a graduate program of study that coincides with the two-year teaching commitment of corps members, who are working on all cylinders during this time.

#4. Depending upon the partnership university’s tuition scale, it’s a matter of location, location, location for corps members’ course fees. Many will carry very large debt in the form of student loans for graduate courses. For example, CM’s who attend the University of Pennsylvania, share that they are leaving with a UPENN grad degree in education that leaves them with about $40,000 in debt.

#5. The AmeriCorps stipend comes to about $22,000 after two years, and that still leaves $20,000 in graduate student loans. Many applicants and corps members are surprised to hear that their graduate study is not free, because they participated in TFA. They thought that’s what they understood from the TFA recruiter. Many believe that all of their undergraduate student debt will be wiped away, but this is not the case. Some don’t realize that they will incur additional graduate student debt for education courses on top of undergraduate debt.

#6. During a dinner last weekend, a guest noted that her niece was graduating from NYU in May, and will be getting a “job with TFA, because it’s a stepping stone to law school.”She was under the impression that law school would be paid for, it its’ entirety because of her niece’s two-year teaching assignment in Philadelphia with TFA.

#7. Some state universities that partner with TFA offer in-state tuition as a benefit for novice Teach For America corps members teaching in their state. The fact that many states are now facing fiscal crunches, undermines whether that decision is prudent. I’m often asked if certified teachers who arrive from out-of-state to teach, would receive the same in-state tuition perk that TFA receives. Unfortunately, residency requirements apply to credentialed and experienced teachers who are seeking advanced degrees.

#8. Many faculty have noted that they can not address some of the burning questions that their TFAers bring to their education classes, because:

a) Formatted PowerPoint slides are given to faculty, prepared by Teach For America, that presents the course content for corps members;

b) Corps members are reticent to discuss some of their realities and concerns with practice¬– teaching special-education, literacy, diversity, differentiation of instruction, classroom management—in a public forum with the education faculty because other class members (Corps members themselves) are likely to share what is said in the context of their education classes, with TFA’s managing directors.

#9. Corps members report that they always excelled in their classes as undergraduates and expect to know that their assignments, readings and graduate course requirements can be compartmentalized. They recall how compartmentalization offered a work/university life balance. But life as novice corps member means that you are juggling your school’s expectations, classroom preparation, TFA’s requirements and e-mail blasts, and university classes. So, free time? Seriously? School realities are often unpredictable and consuming. Days and nights for beginning TFA teachers are often a blur.

#10. Most admit that they never felt so exhausted, have no social life, don’t call home, and have let themselves go (gained weight from food at TFA events) and because they “can’t fit in the time to exercise.”

University classes are viewed as “one more thing that siphons away my time.” The courses and professors teaching become, for some, the one target that they can publicly criticize during their program, without personal repercussions. Publicly critiquing the TFA organization, as an active “corps members,” is not viewed as complying with expectations and doesn’t bode well for those considering post-TFA 100K jobs in leadership and within education reform.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Lloyd Lofthouse and commented:

Discover the real TFA through the story of one of their recruits.

LikeLike

TFA seems to operate for reinforcement of priviledge, thus your discomfort as you bring social awareness to your TFA role. While TFA alum fill administrative roles in all levels of the education field, the relationship between teachers and administrators becomes more destructive. Any depth of experience in educating young people of color becomes a liability, as those relationships are seen as a negative influence. A priviledged person has had ‘expectations’ placed upon them by family and society, while persons of color are steeped in a culture of ‘victimhood.’ Therefore their experience and perspective is toxic to their achievement, and ignorance of that experience is the qualification for your role of savior. Relationships (the foundation of educational experience) become a threat to expectations, as in your experience. So does empathy, and reality.

If awareness of racial injustice and commitment to a community and a neighborhood school cause a teacher to poison their students with ‘low expectations,’ ignorance of social inequity becomes your ticket to success. In this paradigm, members of a low-income community of color are not legitimate role models for their own children. Enter TFA ‘saviors.’ It is an argument for the priviledge to maintain its dominant status, education is only one arena where this toxic (and tragic) dynamic plays out.

LikeLike

Union friendly post-great article! This data/411 can be a terrific validation in the National Education Association.

**Teachers are low paid per educational hours and multiple course enhancements and trainings per other career paths with equal societal impact

**Teach of America professionals EVEN lower pay – with less respect. It is time to stand up an make a change. To be honest, the disrespect is so widespread. Thank you for your post

LikeLike

Thanks Dr. Heilig,

TFA’ “Campus Coordinator” just emailed me to see if they can speak to my undergraduate Research in Urban Education class at Georgia State University. This might be something I can share with them.

I was one of the 7,500+ educators in New Orleans replaced by mostly white TFAs, so I clearly understand what they are about. It’s just a matter of how to present this to undergraduates without coming off as biased.

LikeLike

There is also a primer for engaging TFA supporters written by another TFA alum. See: http://wp.me/p2D92I-1UR

LikeLike

Thank you Ms. Tan. We need more honest stories, and lessons such as yours. From a policy point of view it just jumped out at me how many TFA teachers of Color did not even finish their two year commitment. It also raised the question as to how many teachers of any color who might have built a career at a traditional school in the community as was replaced would be there now?

LikeLike