Today, in response to a nationwide attack on public education, supporters of high-quality, democratically controlled, neighborhood public schools are holding events at the first presidential debate in New York, demanding that the candidates respond to concerns about school privatization and unfair funding, and releasing a national public education platform.

The organizers of the debate protests belong to Journey for Justice Alliance (J4J), a national network of more than 40,000 active members of grassroots community organizations led primarily by people of color in twenty-four U.S. cities. The presidential debate events are co-sponsored by the Network for Public Education Action, a national organization led by Diane Ravitch.

Journey for Justice will host a press conference at Long Island’s Hempstead High School, sponsor a Public Education Nation meeting at SUNY Old Westbury and then hold a rally and march to Hofstra University where the first presidential debate is being held.

Journey for Justice Alliance members who march for equity on Monday are calling for a national equity assessment for public schools in the United States. Funding inequity is readily apparent in public schools in the United States—wealthy neighborhoods usually have better funded public schools—the Alliance also demands a national assessment that considers “curriculum, teacher supports, wraparound supports, student climate and community engagement.”

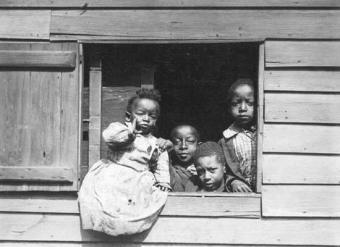

The Journey for Justice Alliance events at the first presidential debate on Monday in New York underscore community-based opposition to the destruction of community public schools and the rise of publicly funded, privately operated charter schools, school takeovers, and over-testing. The events surrounding the first presidential debate are the latest salvo in a black civil war between those who believe in privately operated, market based school choice and those who are are demanding high-quality, properly resourced, democratically controlled, neighborhood public schools.

Make no mistake: there is a civil war going on in the black community. On the one side are charter operators, billionaire foundations, and their acolytes who support the private control of public schools, as envisioned by economist Milton Freidman in the 1950s. On the other side are parents and other stakeholders who are demanding true equity and democracy in our public schools.

National civil rights organizations are divided over this issue. The National Urban League, United Negro College Fund, NCLR and other civil rights groups have typically aligned themselves with market-based school choice proponents. On the other side, the NAACP has passed three national resolutions critical of charter schools over the past six years (the most recent resolution critical of charter schools is awaiting a vote by the NAACP National Board). Black Lives Matters coalition, our nation’s newest national civil rights umbrella group, also released a platform of policy demands critical of charter schools this past summer.

Recently, both sides in the education civil war have focused on communicating to policymakers and the public that they are representing the interests of black families whose communities have been deliberately left behind. Last week charter school owners and their supporters released a letter saying they represent the interests of tens of thousands of black students and bemoaning the NAACP’s most recent resolution criticizing charter schools.

Market-based school choice proponents’ primary agenda has been to promote privately operated “school choice” as the fix for the education of poor children. In contrast, the Journey for Justice Alliance believes that the conversation should be refocused the inequities in our nation. In their platform, they cite lack of equity in public schools as the “major failure of the American education system.”

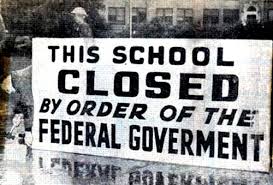

The Alliance’s platform calls for a moratorium on school privatization. That is also the NAACP’s position in a 2016 national convention resolution that calls for a moratorium on new privately operated charter schools.

Over the past two decades, the U.S. Department of Education has spent billions of taxpayer dollars on privately operated charter schools. The alternative vision presented by the Alliance is a federal funding request for 10,000 sustainable community schools. The Alliance’s platform also calls for an end to zero tolerance discipline policies, (also called for by the NAACP’s 2016 charter school convention resolution). The Alliance and the NAACP cite school discipline research by the UCLA Civil Rights Project that found charter schools are even worse than traditional public schools for black and brown students. The Alliance is also calling for ending mayoral school takeovers and appointed school boards and the overuse of standardized tests to justify school takeovers.

Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump may not have much to say on the subject, but equal access to education is a crucial to our democracy, to the American ideal of equal opportunity, and to civil rights.

Julian Vasquez Heilig is a professor at California State University Sacramento and West Coast Regional Progressive Education Fellow. He blogs about education and social justice at Cloaking Inequity.

This article appeared here first at The Progressive Magazine.

We have even come to the point where discussions have occurred that would essentially close entire districts and turn them over to top-down, private control— similar to New Orleans. Dallas and more recently Los Angeles have considered this option.

We have even come to the point where discussions have occurred that would essentially close entire districts and turn them over to top-down, private control— similar to New Orleans. Dallas and more recently Los Angeles have considered this option.

First I’ll discuss Chicago. The problematic outcomes of school closure are readily apparent in the data from Chicago and has been fairly consistently bad news over time. For example, the Chicagoland Researchers and Advocates for Transformative Education (CReATE) found that school closures have historically had a negative impact on children’s academic performance. Analyses of school closures in Chicago reveal that 94% of students from closed CPS schools did not go on to “academically strong” new schools. School closures have not historically resulted in the savings predicted by school officials. Closure-related costs have consistently been underestimated or understated by officials. School closures have exacerbated racial inequalities and segregation in Chicago. Approximately 90% of the school closings have impacted predominately African American communities according to CReATE’s data.

First I’ll discuss Chicago. The problematic outcomes of school closure are readily apparent in the data from Chicago and has been fairly consistently bad news over time. For example, the Chicagoland Researchers and Advocates for Transformative Education (CReATE) found that school closures have historically had a negative impact on children’s academic performance. Analyses of school closures in Chicago reveal that 94% of students from closed CPS schools did not go on to “academically strong” new schools. School closures have not historically resulted in the savings predicted by school officials. Closure-related costs have consistently been underestimated or understated by officials. School closures have exacerbated racial inequalities and segregation in Chicago. Approximately 90% of the school closings have impacted predominately African American communities according to CReATE’s data.

You must be logged in to post a comment.