The purported benefit of the Common Core State Standards over previous sets of standards is the development of critical thinking skills across all subjects, seen as a key lever for increasing American students’ international competitiveness and ameliorating the country’s lethargic economy and persistently high unemployment rates. This perception is clear in statements made by U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan and in articles about the standards (Duncan, 2013; Garland, 2013). Billed as “reflecting the knowledge and skills that our young people need for success in college and careers” (NGA and CCSSO, 2010a). Will a set of standards actually prepare students for life and career?

John Dewey’s vision of reform was a bottom-up approach that focused on the needs of the child and the expertise of the teacher. He warned against a system that relied on a lack of connection between the people in charge of planning for education and the people in charge of actually educating. What would John Dewey think of the Common Core?

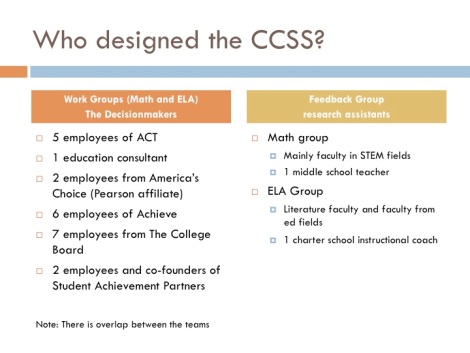

In order to draw a fair conclusion about his potential response, it is worth more closely examining the design process of the Common Core. Explicit documentation of the process that lead to the Common Core State Standards is quite difficult to find. Information from National Governors Association (NGA) press releases indicates that the writing process occurred in two phases. In the first phase, math and language arts “development work groups” worked with respective “feedback groups” to research and write the standards. In the second phase, a “validation committee” reviewed and eventually certified a final product. Members of all groups were nominated by governors and chief state school officers (NGA, 2009a; NGA, 2009b).

Who was in those respective groups? All practicing teachers and school leaders of course…errrrr….

A press release explaining the roles of the groups makes very clear that the feedback group played “an advisory role, not a decision-making role in the process” (NGA, 2009a). Decision-making powers rested with the development work groups. These groups were made up almost entirely of employees of the non-profit organizations Student Achievement Partners and Achieve, and leaders at The College Board and ACT. Among the twenty-nine total members of the teams are three higher education faculty members and one principal (NGA, 2009a).

The feedback group “[provided] information backed by research to inform the standards development process by offering expert input on draft documents” (NGA, 2009a). Members of that group were mainly university faculty from various departments along with one teacher, one charter school instructional coach, and one president of an education non-profit. The “validation committee,” that reviewed and certified the final product. Here in this final step was where teachers, administrators, and many teacher educators could be found. Their role was to verify that each standard was indeed supported by enough research – research on college and career readiness – to warrant inclusion. This group also had the opportunity to add standards provided that they could prove that they were sufficiently research-based. Or to

The lower-level groups represent some experts in academic fields and some knowledge of the classroom, but these people were not leaders in the process. A look into the organizations represented by the development work group – those in control of the process – will give a better sense of the priorities driving the standards. Pearson, The College Board and ACT are probably known to the reader as companies that design standardized tests and test-preparation materials. Student Achievement Partners and Achieve are likely less familiar even though both played central roles in the development of the Common Core State Standards. In fact, their involvement continues in the ongoing implementation process.

Achieve bills itself as a coordinator of sorts and was “founded at the National Education Summit by leading governors and business leaders” (Achieve, Inc., n.d.a) in 1996. Their work is to bring legislators, policy makers, governors, and education and business leaders in the states together to work on solutions to perceived problems. Achieve was part of the leadership in creating the Common Core State Standards and is currently leading one of two efforts to design assessments aligned to the standards. Achieve’s main donors are corporate foundations and private industry companies including many companies rumored to be contributors to the American Legislative Exchange Council (See more Smart ALEC: Education, Privatization, and the Pursuit of Profit and Update on Smart ALEC: Education, Privatization, and the Pursuit of Profit). This is important because it perhaps indicates that Achieve represents the interests of politicians and the private sector, not necessarily students. (Achieve, Inc., n.d.b; Center for Media and Democracy, 2013)

Student Achievement Partners was founded by David Coleman, Jason Zimba, and Susan Pimentel – often named in the media as architects or lead writers of the Common Core. Student Achievement Partners is dedicated solely to implementation of the standards. They have created instructional materials that are offered to educators free of charge through their website and are participating in the design of teacher evaluation tools. Some of their staff members conduct professional development sessions in schools around the country. We do acknowledge that some of these staff members may have had past classroom teaching experience and participated in the creation of the standards through their roles at Student Achievement Partners (Student Achievement Partners, n.d.).

Despite the presence of current educators in some phases of the development of the Common Core, it seems clear that the develop of the standards was external to current classroom educators and school leaders. Testing companies and their affiliates clearly had an outsized role in their development. John Dewey advocated for bottom-up school and school system design grounded in classroom and what was known about the development and interests of children. However, based on the affiliations and interests of the primary developers of Common Core, its development was a top-down approach that clearly reflects the priorities of people in power – testing companies, governors, policy makers, corporations and foundations of great means— but is being sold as Deweyan critical thinking. But is the opposite of Deweyan student and teacher emancipation. So it appears that the Common Core standard development process was not reform, just business as usual. See also Common Core: Same Exclusion, Different Century and Taylor v. Dewey: The 100-year Trickle-Down vs. Pedagogical Debate/Fight in Education Reform

This post is primarily the work and analysis conducted by R. D’Angelo and R. Sanchez

Please Facebook Like, Tweet, etc below and/or reblog to share this discussion with others.

Want to know about Cloaking Inequity’s freshly pressed conversations about educational policy? Click the “Follow blog by email” button in the upper left hand corner of this page.

Twitter: @ProfessorJVH

Click here for Vitae.

Please blame the non-educators who designed the Common Core for any typos. 🙂

Interested in joining us in the sunny capitol of California and obtaining your Doctorate in Educational Leadership from California State University Sacramento? Apply by March 1. Go here.

Relevant References

Achieve, Inc. (n.d.a). About us. Retrieved from http://www.achieve.org/about-us.

Achieve, Inc. (n.d.b). Our contributors. Retrieved from http://www.achieve.org/contributors.

C Burris, & V Strauss. (2013, October 31). A ridiculous common core test for first graders [Web log comment]. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/answer-sheet/wp/2013/10/31/a-ridiculous-common-core-test-for-first-graders/.

Center for Media and Democracy. (2013). ALEC corporations. Retrieved from http://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php?title=ALEC_Corporations

Cremin, L. A. (1961). The transformation of the school: Progressivism in American education, 1876-1957 (Vol. 519). New York: Knopf.

Dewey, John. (1983). The classroom teacher. In J.A. Boydston and A. Sharpe (Eds.), John Dewey: The middle works, 1899-1924 (Vol. 15, pp. 180-189). Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press.

Dewey, John. (1990). The school and society and the child and the curriculum. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Dewey, John. (2010a). My pedagogic creed. In Douglas J. Simpson and Sam F. Stack (Eds.) Teachers, leaders, and schools: Essays by John Dewey (pp. 24-32). Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press.

Dewey, John. (2010b). The teacher and the public. In Douglas J. Simpson and Sam F. Stack (Eds.) Teachers, leaders, and schools: Essays by John Dewey (pp. 241-244). Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press.

Duncan, Arne. (2013). Remarks at the American Society of News Editors Annual Convention [Speech transcript]. Retrieved from http://www.ed.gov/news/speeches/duncan-pushes-back-attacks-common-core-standards

Garland, S. (2013, October 6). Why the common core? The Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/10/15/why-common-core_n_4102763.html

Kliebard, Herbert M. (2004). The struggle for the American curriculum: 1893-1958 (3rd ed.). New York and London: Routledge Falmer.

NGA National Governors Association. (2009a). Common core state standards development work group and feedback group announced [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.nga.org/cms/home/news-room/news-releases/page_2009/col2-content/main-content-list/title_common-core-state-standards-development-work-group-and-feedback-group-announced.html.

NGA National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and the Council of Chief State School Officers. (2009b). Common core state standards initiative validation committee announced [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.nga.org/cms/home/news-room/news-releases/page_2009/col2-content/main-content-list/title_common-core-state-standards-initiative-validation-committee-announced.html

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and the Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010a). Common core state standards. Washington, D.C.: National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and the Council of Chief State School Officers. Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org.

NGA National Governors Association. (2012a). Governors work to implement the common core state standards. Retrieved from http://www.nga.org/cms/home/news-room/news-releases/page_2012/col2-content/governors-work-to-implement-the.html.

NGA National Governors Association. (2012b). Trends in state implementation of the common core state standards: Educator effectiveness [PDF document]. Retrieved from http://www.nga.org/cms/home/nga-center-for-best-practices/center-publications/page-edu-publications/col2-content/main-content-list/trends-in-state-implementation-o.html.

NGA National Governors Association. (n.d.). Common core state standards initiative standards-setting criteria [PDF document]. Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org/assets/Criteria.pdf.

NCEE National Commission on Excellence in Education (1983). A nation at risk. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/pubs/NatAtRisk/index.html.

Ravitch, Diane. (1995). National standards in American education: A citizen’s guide. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution.

Ravitch, Diane. (2010). The death and life of the great American school system: How testing and choice are undermining education. New York: Basic Books.

Simpson, Douglas J., & Stack, Sam F. (Eds.). (2010). Teachers, leaders, and schools: Essays by John Dewey. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Student Achievement Partners. (n.d.) Principles and purpose. Retrieved from http://www.achievethecore.org/about-us

United States Department of Education (2001). No child left behind executive summary.

Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/nclb/overview/intro/execsumm.html.

United States Department of Education (2009). Race to the top executive summary.

Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/programs/racetothetop/executive-summary.pdf.

United States Congress, 103rd Congress. (1994). H.R. 6 Improving America’s schools act, section 1111: state plans. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/legislation/ESEA/sec1111.html.

McNeil, L., & Valenzuela, A. (2001). The harmful impact of the TAAS system of testing in Texas: Beneath the accountability rhetoric. In M. Kornhaber & G. Orfield (Eds.), Raising standards or raising barriers? Inequality and high stakes testing in public education (pp. 127-150). New York: Century Foundation.

Vasquez Heilig, J. & Nichols, S. (2013). A quandary for school leaders: Equity, high-stakes testing and accountability. In L. C. Tillman & J. J. Scheurich (Eds.), Handbook of research on educational leadership for diversity and equity, New York: Routledge.

Vasquez Heilig, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2008). Accountability Texas-style: The progress and learning of urban minority students in a high-stakes testing context. Educational evaluation and policy analysis, 30(2), 75–110.

Vinovskis, Maris A. (2009). From a nation at risk to no child left behind: National education goals and the creation of federal education policy. New York and London: Teachers College Press.

I’m sorry, but I think you’ve missed the mark on Common Core here. Two points, one is that the CCSS do a fairly good job of focusing on critical thinking skills and higher order thinking skills, particularly when compared to previous state standards. The other is that higher expectations have been shown to be particularly important and valuable for minority students who suffer the most from low expectations, and benefit the most from higher expectations.

I can only speak to the development of the Math CCSS, but the MATH CCSS follow closely the NCTM Principles and Standards for School Mathematics. They did not need to be rewritten because they had already had large amounts of input and research backing. The NCTM math standards had been introduced in 1989 and in a state of improvement since then. Compare the CCSS Standards for Mathematical Practice (http://www.corestandards.org/Math/Practice/) to the NCTM Process Standards (http://www.nctm.org/uploadedFiles/Standards_and_Positions/PSSM_ExecutiveSummary.pdf) then compare those to the complete lack of higher order thinking skills required in just about every previous set of state standards. Further reading through the actual CCSS shows that the standards do ask for more focus on higher order thinking.

In summary the CCSS standards themselves are an improvement over the existing standards. Implementation of the CCSS may be and in many cases is far from ideal, but that is separate from the issue of the quality of the CCSS themselves. The problem is a lesson or text that claims to follow the CCSS or a particular CCSS standard is referred to or refers to itself as a CCSS lesson or curriculum. Then the failings of the lesson or curriculum are judged as failures of the CCSS when they have nothing to do with the CCSS.

LikeLike

This is well written and I am happy, for once, someone was taking the high road in acknowledging that Common Core had several leaders involved that had/have teaching experience.

What I do not understand is that this process is not different in our schools and businesses. Before Common Core we would all mumble under our breaths about principles, BOE and Superintendents were making decisions and forcing teaching requirements down our throats while state legislators were doing the same with testing. Nothing has changed, we just put a new face on the enemy. We want a say then complain about the say, we want to be charged with being the experts and professionals but we don’t want to be held to that standard… No offence, but our biggest enemy may actually be ourselves. Maybe we just thrive on negativity or maybe we are more focused on ourselves. Maybe it is not the process of being able to guide a child’s development but the need to be the person in charge of what is imparted rather than the act itself; a selfish motivation. Maybe it is this that separates those who love to teach and those who love to help children grow socially, emotionally and academically.

LikeLike

Just found your blog and am loving all of these posts. I am currently a grad student at NYU’s English Ed (7-12) program and have gotten into a lot of discussions of the Common Core and Dewey (separately). I really appreciated the way you tied the two together. I’d like to see what a Common Core would look like if it was developed by a group of teachers and if the group had a more diverse representation in race. What difference would we see in the Standards themselves? What might be prioritized that is not currently?

LikeLike

One of my heroine’s from Louisiana -and likewise greatly effected by Hurricane Katrina that brought her home is Mercedes K. Schneider. Her recently published book, “A Chronicle of Echoes: Who’s Who in the Implosion of American Public Education” should be part of this discussion. Thanks.

LikeLike

Julian:

First – thank you for your consistent work re: the CCSS and education reform in general!

Second: Check out “The Origins of the Common Core: How the Free Market Became Education Policy” by Dr. Deborah Owens and published by Palgrave MacMillan and coming out in January 2015. http://www.palgrave.com/page/detail/the-origins-of-the-common-core-deborah-duncan-owens/?K=9781137482679

Since I wrote the forward I can say that you are quoted in the book, and I think what this book explains as the title makes clear, will help you and so many others in preserving our public school system. Also see Deb’s little blog that gives further insights into the book.

http://publicschoolscentral.com/

Again, for all the supporters of America’s public schools – thank you for your work!

Tom

LikeLike

Excellent post. I am teaching John Dewey’s Education and Democracy this semester and agree that education reformers are betraying Dewey’s vision. They use democratic words for corporate ends.

I wonder why, though, the article has an adjacent picture of Linda Darling-Hammond with a description of her as a heroine. This month, the Alliance for Excellent Education released a report calling for a Common Core statewide accountability system. One of the authors: Linda Darling-Hammond.

http://all4ed.org/webinar-event/oct-16-2014briefing/

LikeLike

Linda was my dissertation advisor. So she’ll be my heroine no matter what. 🙂

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Shared Intentions and commented:

Point taken — and the Deweyan criticism of CCSS may go far deeper still.

LikeLike